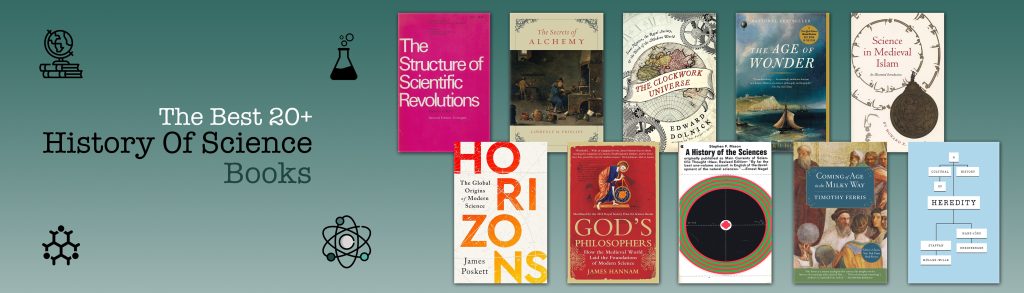

Exploring the evolution of science through the lens of history not only enriches our understanding of the natural world but also illuminates the profound impact scientific discoveries have had on society and human thought. The best history of science books weave together compelling narratives of innovation, daring pursuits of knowledge, and the relentless quest to understand the universe’s mysteries.

These history of science books span across various disciplines, from the astronomical observations of ancient civilizations to the groundbreaking experiments in physics and biology that defined the modern era. This list of history of science books aims to guide readers through a curated selection of distinguished titles that reveal the intricate tapestry of scientific advancement and its indelible mark on human history.

Scientific discoveries have had a monumental impact on the fabric of society, revolutionizing how we live, think, and interact with the world around us. These breakthroughs often serve as catalysts for further innovation, setting the stage for advancements in technology, medicine, and industry. Beyond the tangible, the pursuit and application of scientific knowledge have profoundly influenced philosophical and ethical conversations, challenging existing beliefs and inspiring a deeper inquiry into the nature and purpose of our existence. The ripple effects of these discoveries underscore the interconnectedness of science and society, driving progress and shaping the course of human history.

The Very Best History of Science Books

The 20+ history of science books listed below promise more than just an academic foray into the chronicles of scientific inquiry; they serve as a testament to the nobility of the human spirit. Engaging with these history of science books, readers will find themselves on a profound journey that not only charts the monumental leaps in human understanding and capability but also invites a deeper introspection into their personal ethos and worldview.

These history of science books do not merely recount historical events; they challenge us to think more critically about the role of science in shaping societal values, ethical considerations, and our collective aspirations. In essence, they make us more noble, enriching our appreciation for the relentless pursuit of knowledge and the indomitable desire to make the world a better place.

Have you ever set out to find one thing and ended up discovering something completely different? This delightful twist of fate happens not only in our lives but also in the world of science. In “Serendipity: The Unexpected in Science,” Telmo Pievani explores this thrilling phenomenon by sharing fascinating stories of accidental discoveries that have shaped modern society.

He compellingly recounts instances like Archimedes, who uncovered the principle of buoyancy in his bathtub, or the serendipitous invention of inkjet printers, born from an engineer’s moment of curiosity. The journey even meanders through the discovery of coffee, which started with a shepherd observing his sheep’s unusual excitement after a particular fruit was eaten.

What stands out in this book is not merely the whimsy of coincidence but the deeper message that persistence in pursuit can lead one to unexpected, yet significant, findings. Pievani artfully illustrates that behind every well-known genius lies a story of curiosity mixed with a dash of luck. This serves as a gentle reminder to young and old alike that great discoveries often require a blend of exploration, intelligence, and a bit of fate.

Serendipity: The Unexpected in Science is an ideal read for anyone keen on popularizing science, offering captivating tales that can inspire curiosity in young minds. My hope is that this book can spark curiosity in students, leading them—aided by inspired teachers—on their own journeys towards remarkable discoveries that might just change the world. Whether you are a science enthusiast or just someone looking for an enjoyable read, Pievani’s work captures the enchantment of the unexpected beautifully.

The Middle Ages, a period often pejoratively dubbed as the ‘Dark Ages’, is frequently overlooked when we recount the history of scientific progress. But James Hannam’s “God’s Philosophers” shines a light on this misunderstood era, revealing the essential contributions of medieval scholars to the development of modern science. With a robust and enlightening narrative, Hannam upends the entrenched biases that have led many to dismiss the period as one of stagnation and blind adherence to dogma.

At its heart, “God’s Philosophers” is a vivid celebration of the intellectual endeavors that marked the medieval period. Hannam meticulously chronicles the works of lesser-known figures such as John Buridan, Nicole Oresme, and Thomas Bradwardine, alongside the contributions of more renowned thinkers like Roger Bacon, William of Ockham, and Saint Thomas Aquinas. These are the minds that laid the bedding for what would later bloom into the Scientific Revolution.

One of the book’s most compelling aspects is its myth-busting approach to history. Hannam deftly debunks the common misconceptions that medieval scholars thought the Earth was flat or that the Inquisition was a relentless enemy of scientific discovery. He illustrates how, contrary to popular belief, Christianity and Islam played supportive roles in the pursuit of knowledge during these times.

“God’s Philosophers” does not shy away from religious contexts; instead, it examines how faiths were intertwined with scientific inquiry. Hannam provides a nuanced perspective on how Christian and Muslim teachings fostered an environment ripe for scientific exploration, contributing to groundbreaking advances in fields as diverse as mathematics, physics, and astronomy.

The book offers a window into significant technological innovations, such as the creation of spectacles and the mechanical clock—tools that reshaped daily life and understanding of the world. These creations speak to the creativity and ingenuity of medieval inventors, who were not just precursors but pioneers in their fields.

James Hannam successfully strikes a balance between scholarly attention to detail and accessible storytelling. Readers are treated to a rich tapestry of history that connects the dots between the medieval world and the onset of modern science. By the end of “God’s Philosophers,” Hannam has convincingly established that the scientific enlightenment didn’t materialize out of a vacuum; it was deeply rooted in the intellectual soil of the Middle Ages.

“God’s Philosophers” is not just a necessary read for those interested in the history of science; it’s a crucial corrective to the historical record, reminding us that knowledge is a cumulative endeavor reaching far back into our shared past. Anyone with a curiosity about the origins of modern scientific thought or the cultural context of the medieval world will find this book to be an enlightening and thought-provoking adventure.

The narrative might challenge deeply-held assumptions, but it is this challenge that makes “God’s Philosophers” a significant contribution to the historiography of science. Readers will walk away with a renewed respect for the medieval scholars who, long before Galileo and Newton, helped to chart the course toward our contemporary understanding of the universe.

The quest to transform the mundane into the marvellous might seem like a tale spun from the fabric of fantasy, yet in The Secrets of Alchemy, Lawrence M. Principe unveils the rich tapestry of truth behind such pursuits. Principe, a science historian and chemist, articulately navigates through the fog of misconceptions surrounding alchemy, revealing its raw and enigmatic beauty.

At its heart, “The Secrets of Alchemy” aligns itself not with tales of conjuring gold from lead but with a much deeper narrative—one filled with a diligent quest for knowledge and comprehension of the natural world. Principe masterfully demonstrates the pivotal role of alchemy in early modern Europe, extending beyond the bounds of mere proto-chemistry to influence literature, fine art, theater, and religion.

One of the most striking aspects of Principe’s work lies in his portrayal of the alchemists themselves—thinkers and artists like Zosimos and Basil Valentine, whose contributions to alchemy stretched from its dominance in the third century to an enduring cultural legacy. The author personifies alchemy through these larger-than-life figures, piecing together historical puzzles from ancient texts and even attempting to recreate famed alchemical recipes.

In tandem with Principe’s exploration, Howard Turner’s historical overview provides context to the spread of Islamic civilization and its indelible impact on the scientific landscape. This confluence of cultural and scientific dissemination spotlights the assimilation and growth of knowledge across Greek and Chinese traditions while showcasing Islamic brilliance in various scientific disciplines. Turner’s work acts as a subtle reminder of the interconnectedness of global intellectual progress and cultural diffusion.

The book‘s intricate melding of the historical, chemical, and philosophical aspects of alchemy allows the reader to grasp the nuance of this oft-misunderstood practice. Through Principe’s impassioned prose and rigorous scientific insight, we learn that alchemy is more than the quixotic pursuit of gold-making—it is a venerable intellectual tradition that sparked inquiry and innovation.

“The Secrets of Alchemy” is a compelling read for anyone intrigued by the intersection of science and history. It illuminates the misunderstood shadows of alchemy and, in doing so, realigns our historical lens to appreciate the profound legacies of alchemists and the civilizations that fostered their quests. It also serves as a poignant reflection on the ebb and flow of scientific thought across time and geography, emphasizing the timeless human desire to understand the mysteries of our world.

In this book, readers uncover not just the secrets of a bygone era but also the reverberations of ancient wisdom in our modern era. Principe stands as both historian and scientist, unraveling the gold threads woven through history’s fabric, and what a splendid weave it is—the kind which, only after reading this book, one truly appreciates for its worth beyond base metal.

In “A Cultural History of Heredity,” authors Staffan Muller-Wille and Hans-Jorg Rheinberger pull back the curtain on the intricate tapestry of history, politics, and science that has shaped our understanding of heredity. This explorative text sheds light on how heredity, which we now regard as a core principle of biology, was once merely a peripheral idea in cultural and scientific dialogues.

Encapsulating a span of over two centuries, the book starts by laying out the premodern theories of generation, underlining that the focus during those times was more on individual procreation rather than on the transmission of hereditary traits. It opens up discussions on how and why hereditarian thinking first permeated fields as diverse as politics, law, medicine, natural history, and anthropology.

Fast forward to the late 19th century; Muller-Wille and Rheinberger engage readers in the evolution of heredity theories amidst the growing societal concerns over race and eugenics. The authors then trace the path leading to the advent of classical and molecular genetics in the 20th century, illustrating these developments’ relation to the prevailing socio-political milieu.

This narrative continues as the book illustrates the contemporary landscape where sophisticated information technologies are harnessed to decode heredity, emphasizing the concept’s paramount importance in the life sciences and broader culture.

Unexpectedly, the book intertwines alchemy’s history and the tale of its practitioners into the discussion of heredity. The authors convey how alchemy’s mysterious texts and practices unfold the understanding of scientific concepts over the ages.

Furthermore, the book offers a nuanced perspective on Islamic civilization’s contributions to the scientific sphere. Howard Turner’s exploration into this era reveals how the Islamic pursuit of knowledge not only conserved but also enhanced the scientific heritage of older civilizations, intricately influencing modern Western science.

One of the most commendable aspects of this book is its interlacing of multiple disciplines to narrate the developmental history of a scientific concept. However, some may find the detours into areas like alchemy and the scientific accomplishments of Muslim civilization a stretch from the main topic. Yet, these forays are valuable in their own right, offering a holistic view of heredity’s place within the grand narrative of human exploration and knowledge.

The book is meticulously researched and rich in detail, which may both be its strength and downside. While it serves as an intellectual feast for those fascinated by the history of science or sociology, lay readers may find themselves wading through dense, jargon-laden passages.

“A Cultural History of Heredity” is no light read; it demands an attentive and contemplative reader. Yet, the payoff is immense for those willing to immerse themselves in the intricacies of its discourse. Muller-Wille and Rheinberger have crafted a work that impressively contextualizes the concept of heredity within a broader cultural and historical backdrop, thereby enriching our understanding of the origin and significance of the ideas that shape contemporary science.

For students and scholars alike, this book serves not just as a mere recounting of facts but as a thought-provoking chronicle, inviting readers to reflect on the interconnected web of factors that have driven the scientific pursuit of heredity throughout history.

“Science in Medieval Islam,” authored by Howard R. Turner, is a fascinating voyage into the rich scientific heritage that flourished during the Golden Age of Islam. The book serves not just as a recount but as an ode to the pioneering spirit of Muslim scholars whose insatiable quest for knowledge laid the fragmented bricks on which modern science has built its edifice.

Turner’s well-researched narrative takes the reader on a historical odyssey, beginning with the rapid expansion of the Islamic empire. Stepping into the shoes of the seventh-century scholars, the reader is immersed in an environment where knowledge from Greece and China was absorbed, assimilated, and amplified. One cannot help but be awe-struck by the civilization’s awe and veneration for learning.

The core of the text deal with the scientific endeavours and advances that emanated from this period. Ranging from cosmology to medicine, Turner encapsulates the essence of an era where the quest for understanding was truly holistic. The book illustrates a culture that found harmony between empirical inquiry and spiritual piety—a conjunction not often noted in contemporary scientific discourse.

Particularly captivating are the chapters on mathematics and astronomy, revealing the origins of much of the numerical and celestial knowledge taken for granted today. One can trace the lineage of algebra back to the Islamic scholars’ dedicated research, and Turner does a stellar job of connecting those dots.

What is equally commendable is the author’s articulation of the ripple effect Islamic science had on the Renaissance and subsequent epochs. Rather than presenting this influence as a footnote, Turner highlights it as an integral plot point in the story of human progress.

While delivering an academic and intellectual treatise, the book also heavily feeds on visual captivation. Its rich illustrations not only provide an aesthetic allure but also serve as an educational scaffold, helping to ground abstract concepts in tangible artifacts.

However, for readers seeking in-depth technical analysis of the scientific theories discussed, the book treads lightly. It’s a trade-off that makes “Science in Medieval Islam” readily accessible to a broad audience but might leave experts yearning for more density.

In conclusion, Howard R. Turner’s “Science in Medieval Islam” is an essential read for anyone inclined towards understanding the contributions of an oft-overlooked era in the tapestry of scientific history. It’s a book that inspires both respect for the past and contemplation on how its legacies shape our current scientific understanding. Turner illuminates a treasure trove of knowledge that compels the modern reader to reevaluate the sources of our own culture’s intellectual capital.

“A People’s History of Science” by author Clifford D. Conner challenges the traditional narrative of scientific progress by bringing to light the cumulative and democratic nature of scientific knowledge. This thoughtful piece of literature upends the classic portrayal of solitary geniuses in favor of a more inclusive view that includes the countless contributions of “ordinary” individuals.

Conner’s work asserts that scientific achievements are not merely the milestones set by a handful of renowned individuals. According to his perspective, contributions from various layers of society have laid the groundwork for these scientific luminaries to achieve their famed breakthroughs. The real story of science is one that involves a collective effort, with people from different walks of life adding to the rich tapestry of understanding that we have today.

One of the book’s most engaging elements is its emphasis on how science has impacted the daily lives of ordinary people, as well as how these everyday individuals have perceived and influenced scientific progress throughout history. The text suggests that rather than being passive observers, the general populace has always played a role in the development of scientific thought, whether they were the sophisticated thinkers or not.

For instance, the book presents the notion that practical knowledge from farmers, sailors, miners, blacksmiths, and midwives has historically informed scientific inquiry. They may not have had their theorems enshrined in the annals of history, but their empirical experiences and problem-solving capabilities have undeniably underpinned the advances we attribute to the famous figures of Newton, Galileo, and Einstein.

“A People’s History of Science” doesn’t diminish the complexity or the wonder of monumental scientific theories; instead, it enriches the history by showcasing the foundational efforts—often overlooked—that make the pinnacle achievements possible. Conner’s narrative equates modern science to a skyscraper, where the high-floor marvels can’t exist without the broad and sturdy base provided by the masses.

Conner’s prose is evocative and accessible, which makes the subject matter inviting for readers who aren’t steeped in the annals of scientific history or familiar with academic jargon. It opens up dialogues about the nature of scientific progress and calls into question who we celebrate and why. In essence, it democratizes the notion of scientific brilliance and emphasizes the value of collective human experience.

For those seeking to understand the true nature of scientific evolution or for readers interested in a more inclusive and collective account of scientific endeavor, “A People’s History of Science” is an enlightening and thought-provoking read which reminds us that science, at its core, is a profoundly human endeavor.

In summary, Clifford D. Conner’s “A People’s History of Science” posits a profoundly democratic view of scientific achievement, changing the way we think about who creates knowledge and how it is shaped by all of society. It’s a compelling read for anyone who believes in crediting the many over the few and recognizes that science is as much about the uncelebrated trials and errors as it is about the celebrated eureka moments.

“The Age of Wonder: The Romantic Generation and the Discovery of the Beauty and Terror of Science” is a magisterial work by Richard Holmes that transports readers to the seminal age of scientific discovery in the late eighteenth century, a period that intertwined with the onset of Romanticism. Holmes artfully navigates the intellectual landscape of the era, revealing how science and the arts were not disparate realms but rather entangled threads in the fabric of the time.

Central to the book is the notion that the age was marked by a dual sentiment towards science; it was both beautiful and terrifying, capable of illuminating the mysteries of nature while also opening a Pandora’s Box of new philosophical questions and existential uncertainties. The figures prominently featured in the narrative represent pillars upon which the second scientific revolution was built.

Joseph Banks, with his insatiable quest for the botanical unknown, begins the tale with a voyage that brought the Enlightenment spirit to exotic shores. William Herschel and his sister Caroline extend the human gaze to the furthest reaches of the cosmos, revolutionizing our understanding of space. Meanwhile, Humphry Davy’s experiments, although perilous, set the foundation for modern chemistry. These vivid accounts are not merely biographical but are also reflective of the broader societal implications of their work.

The synergy between science and art is made tangible through the inspiration these scientific trailblazers provided to contemporaneous creatives such as Mary Shelley, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and John Keats. Their responses to scientific progress, ranging from optimistic to wary, offer a poignant lens on the reception of scientific advancement. Holmes captures their reactions as emblematic of a sociocultural tide where Romantic literature was in dialogue with scientific dialogue.

Holmes’s prowess as a writer shines not only in the thoroughness of his research but also in his stylistic choice to approach history from a narrative standpoint, which imbues the text with a novelistic allure. Through vibrant character portrayals and detailed scenes, he makes bygone epochs resonate with the immediacy of contemporary concerns. The prose is accessible, richly descriptive, and infused with an infectious passion for the subject matter.

While chronicling key figures and their achievements, “The Age of Wonder” also navigates the larger debates they prompted. Holmes does not shy away from discussing the societal impacts and moral conundrums that accompanied these scientific leaps. In this sense, the book is not just a history but also a meditation on the nature of progress and the ethos of discovery.

“The Age of Wonder” is a profound ode to an era that reshaped humanity’s understanding of the world and its place within it. Richard Holmes has stitched together the biographical, scientific, and cultural fibers into a cohesive and engaging narrative that will appeal to both fans of history and those with a keen interest in how our scientific lineage informs the present day.

For anyone captivated by the intersectional dance of science and the humanities, Holmes’s work is indispensable reading. His historical acumen and storytelling prowess make this book a compelling venture into the past that is full of implications for our future. The beauty and terror of science, as chronicled in this enlightening volume, continue to resonate in our collective quest for knowledge.

“The Disappearing Spoon,” penned by science writer Sam Kean, is not merely a book; it’s a kaleidoscope through which the periodic table reveals tales that oscillate between madcap and poignant, underpinning the human and scientific narratives behind each element.

The title itself is derived from a prankish property of the element gallium—a metal that can be crafted into a spoon that melts away in a hot cup of tea. This anecdote ushers in the reader to a dimension where chemistry not only bonds elements but weaves the very fabric of history, politics, and passion.

Kean masterfully blends the factual rigidity of the table where elements reside with the mutable human conditions they partake in. For instance, he intricately outlines the tumultuous connection between radium and the sullied repute of Marie Curie, and regales readers with why gallium is the substance of choice for lab jesters.

Each chapter takes on an element and extracts its tale not just from science, but from its mysterious role in historical anecdotes, wars, economies, and personal downfalls. For the science enthusiasts, the book is an endless corridor of ‘aha moments’, while for the uninitiated, it’s an inspiring narrative that makes one wonder about the seemingly mundane entries in the periodic table.

Kean has the knack for crystallizing complex scientific ideas into laic simplicity and draw connection to overarching themes of love, madness, and the pulsating quest of human spirit through exploration and discovery.

The book‘s progression follows a loose structure, which might appear disorganized to readers who expect a linear narrative. However, this non-linearity lends the book the charm of unpredictability—each chapter is a new adventure, a standalone treat. Readers might also find themselves swiveling back to previous chapters, making connections between stories and elements like a detective joining dots in a cold case.

On the other hand, while experts might value “The Disappearing Spoon” for its widespread tales, they might critique the lack of depth in scientific rigor. But then again, the book aims to enthral rather than educate, succeeding more at stirring curiosity than acting as a textbook substitute.

Ultimately, “The Disappearing Spoon” is a treasure trove for anyone who appreciates science for its arcane stories and bizarre tidbits, not just its formulas and laws. Kean does not just write about the elements; he celebrates them in a tome that is equal parts educational and entertaining. It champions the idea that science, like art, has its own texture, dramas, and unforeseen ramifications when it intersects with the unpredictability of human behavior.

The Disappearing Spoon is highly recommended for those ready to have their interest in science rekindled or for anyone curious enough to learn how elements can be recast as main characters in the unfolding drama of our universe.

Timothy Ferris’s “Coming of Age in the Milky Way” traces the grand arc of scientific discovery from ancient stargazers to the grand enigmas of current-day physics. Through his meticulous research and engaging narrative, Ferris not only unravels the cosmos but also the captivating lives of the astronomers and physicists who have contributed to our understanding of it.

This is not just a book about the science of astronomy; it is also about how this science came to be. Ferris expertly navigates through historical breakthroughs and the resistance early astronomers faced from the societal norms of their times. Themes of conviction, curiosity, and the resultant struggle against the establishment weave through the narrative. Through rich storytelling, the book paints intimate portraits of scientific giants such as Ptolemy, Copernicus, Galileo, Newton, and Einstein, emphasizing their humanity alongside their monumental achievements.

One of the book’s greatest successes is how it chronicles the evolution of scientific thought regarding the universe while mirroring this advancement with humanity’s own ‘coming of age’. Ferris makes clear that our grasp of the universe is intimately linked to the tools we have at our disposal and the freedoms permitted by the cultural climate in which we wield them.

The author’s use of language is another highlight; his prose has a poetic quality that captures the awe of the cosmos. He discusses complex concepts in terms that are accessible without sacrificing their inherent wonder. “Coming of Age in the Milky Way” thus becomes not just a recounting of astronomical progress but an homage to the power of human thought and ingenuity.

It is also a reminder of the humility we must maintain as we explore the cosmos. As much as the book is a story of triumph, of humanity’s relentless push for knowledge, it also underscores our current position at the cusp of the unknown—perhaps our real ‘coming of age’ moment, as we peer into the abyss of dark matter and further mysteries of the universe.

For those interested in the history of science, in the stories of human tenacity against dogma, and in the sheer beauty of the vast world above us, “Coming of Age in the Milky Way” is a profound read that will inspire awe and reflection.

In essence, Ferris doesn’t just tell us about the stars—he brings us along on the millennia-spanning quest to understand them, making us feel a part of this ongoing story, one which we all, knowingly or not, are a part of. Whether a seasoned astronomer or a casual reader with a curious eye to the sky, this book is an enlightening excursion through the annals of cosmic exploration that encourages us to wonder, question, and dream.

“The Clockwork Universe: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society, and the Birth of the Modern World” is a mesmerizing tale that transports readers back to the cusp of the modern age, a time riddled with conflict, disease, and superstitious dogmas.

Author Edward Dolnick masterfully recounts the lives and discoveries of the founding fathers of modern science against the dramatic backdrop of the 17th century. Through meticulous research and engaging storytelling, Dolnick weaves the tale of a group of visionary men, including the likes of Isaac Newton, who dared to envision a universe governed by laws as precise as the gears in a clock.

The book underscores a period rife with turmoil, where plague swept through streets and religious wars left indelible marks on society. Yet, amidst this disorder, a band of intellectuals connected by their thirst for knowledge and their membership in the then nascent Royal Society, set forth principles that would dismantle and reconstruct the world’s understanding of nature.

What stands out in Dolnick’s portrayal is the striking paradox of the age—brilliant minds bound by the mysticism and irrational beliefs of their time. The reader witnesses the transformational period where magic began its descent as the mechanistic view of the cosmos ascended, driven by mathematics and observable facts.

At the heart of the story is Isaac Newton, one of history’s most enigmatic figures—an alchemist and scientist who could fathom the laws of motion and gravitation, yet spent countless hours searching for hidden messages in the Bible and studying alchemy. Dolnick doesn’t shy away from presenting the full scope of Newton’s obsessive genius, giving us a character that is deeply human in his complexities.

“The Clockwork Universe” doesn’t just recount historical events—it grips readers with a compelling narrative, challenging them to appreciate the tumultuous revolution of thought that gave birth to modern science. By bridging the divide between scholarly work and popular science, Dolnick ensures that readers of all backgrounds can appreciate this turning point in our intellectual history.

In “The Clockwork Universe,” enlightenment comes alive with vivid descriptions and intimate details of the characters’ lives. Dolnick’s work is not just a testament to human curiosity and the relentlessness of progress—it’s an ode to the unyielding spirit that continues to drive scientific discovery today.

Readers will leave with a greater appreciation for the order we’ve come to expect in the natural world, and for the flawed, yet formidable, individuals who gifted us this understanding. It’s a must-read for anyone who seeks to comprehend the profound shift from the mystical to the mathematical, from alchemy to science, from a world fraught with chaos to one ticking with the precision of a clock.

In a rating, I’d give “The Clockwork Universe” a well-deserved 4.5 out of 5 stars, for not only illustrating a pivotal historical era but for affirming the power of human resolve against the tapestry of time itself.

A History of the Sciences offers an expansive and rigorous exploration into how human understanding of science has evolved from its embryonic stages in ancient civilizations to the sophisticated tapestry of knowledge we see today.

At its core, the book grapples primarily with the advancement of scientific thought and methodology through the ages. The author deftly navigates through the early curiosities and astronomical quandaries of ancient Babylonians to the meticulous empirical observations of the Renaissance, and eventually onto the frontiers of quantum physics and beyond. Reflecting on modernity, the book confronts how today’s cultural pulse and technological innovation shape—and often expedite—scientific exploration and acceptance.

A History of the Sciences stands out for its depth of research and its panoramic perspective. Not satisfied with simply cataloging historical events, the author penetrates the very ethos of each era, questioning how cultural mores and worldviews steered the directions and fates of scientific breakthroughs. This is a narrative that does not shy away from the complex interplay between science and society—a dynamic that is both shaped by and shapes the generation of knowledge.

A History of the Sciences charges into the nuances of paradigm shifts, digging into the minds of key figures whose sparks of genius altered the trajectory of human knowledge. It’s a study of brilliant minds straddling the line between heresy and visionary insight, of knowledge gained not solely by success but often through the instructive power of failure and misunderstanding.

With elegant prose, A History of the Sciences elucidates the often-mysterious nature of scientific discovery, making it accessible and riveting. However, readers may find portions heavy with technical jargon, a small hurdle for those less scientifically inclined. Still, the author takes great care to weave explanation into the narrative fabric, which aids comprehension and enriches the story being told.

Today’s scientific efforts are painted against the backdrop of urgent global issues and technological prowess, making “A History of the Sciences” incredibly timely. One can’t help but reflect on the social responsibilities and ethical boundaries of those who wield the double-edged sword of knowledge in an age where information is both currency and power.

“A History of the Sciences” is a heavyweight champion in the genre of historical non-fiction. Both grand in scale and meticulous in detail, it carves out a clear path through the tangled undergrowth of scientific progress, providing readers with insights not only into the milestones of scientific achievement but into the very DNA of discovery itself. This book should find a deserving place on the shelves of students, educators, and anyone with a vested interest in the chronicles of human understanding.

For curious minds and stargazers, for those who dare to dream big and question deeper, “A History of the Sciences” is more than a book—it’s a pilgrimage through the annals of our quest for knowledge. And what a profoundly fascinating pilgrimage it is.

Isaac Asimov, a name synonymous with science fiction, was not only a prolific writer of novels and short stories but also an exceptionally knowledgeable commentator on the history of science. His “Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology,” though perhaps less well-known than his robot or Foundation series, is a testament to his deep understanding and appreciation of scientific progress.

The ambitious tome is a detailed catalog that chronicles the lives and achievements of approximately a thousand scientists. These biographical sketches span from antiquity to the time of the book’s publication, creating a timeline of scientific exploration and discovery that is unparalleled in its breadth.

The most striking feature of this encyclopedia is how it contextualizes each scientist’s contributions within the larger framework of scientific development. Each profile not simply lists dates and discoveries; it links individual achievements to the overall structure of scientific thought and progress. This interconnectivity between the sciences and scientists across different eras serves as a reminder of the collective endeavor that scientific inquiry truly is.

The profiles, though concise, provide more than just factual summaries. They offer insights into the often convoluted paths of scientific achievement and highlight the creative and sometimes serendipitous nature of discovery. It’s a valuable reference book for anyone interested in the history of science and the remarkable individuals who have contributed to it.

Asimov’s approach to the biographical format is not dry, as one might expect from an encyclopedia. Instead, there’s a clear effort to keep the material accessible and engaging. Nonetheless, it cannot be denied that the sheer volume of content can be overwhelming. This is a book best digested in small portions, offering bite-sized enlightenment rather than extended narrative pleasure.

Another aspect of Asimov’s writing that deserves praise is his ability to evaluate scientific work without bias. His summaries are not laden with personal opinions but rather strive to present a fair assessment of each scientist’s impact on their field.

While the book‘s last edition was published decades ago, it still stands as a significant resource today. The historical perspective it provides is valuable not only to those specifically interested in science but also to readers keen on understanding how our current technological world came to be.

Where it falls short, however, is in the inevitable absence of more recent scientific figures and breakthroughs — a limitation of any historical record that ceases to update. Nonetheless, for its time and even today, it provides a sturdy foundation upon which to understand the ancestry of scientific accomplishment.

“Asimov’s Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology” is more than a mere collection of bios; it is an ode to humanity’s quest for knowledge. Its expansive vision makes it a treasure trove for both academic and personal libraries. Yet, it should not be regarded as a definitive end but as a starting point for anyone looking to explore the rich tapestry of our scientific heritage.

Asimov’s Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology earns a solid recommendation for its meticulous and comprehensive accounting of science history. Isaac Asimov’s legendary storytelling proficiency may shine brightest in his fiction, but his passion for science itself is nowhere more evident than in this encyclopedic homage to the trailblazers of technology and discovery.

Randall Munroe, the creative genius behind the wildly popular webcomic xkcd, invites readers on a thought-provoking, laughter-inducing exploration of the absurd in his book, What If? Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions. Known for his clever stick-figure drawings that touch upon themes of science, technology, language, and love, Munroe tackles the kind of outlandish questions that might have crossed your mind but you never dared to ask out loud.

With a unique blend of rigorous scientific analysis and a sharp sense of humor, Munroe seeks to answer bizarre questions ranging from the outcomes of hitting a baseball at near-light speed to the consequences of driving over a speed bump at the maximum survivable speed. His method? Running computer simulations, digging through declassified military research, solving complex equations, and conversing with experts like nuclear reactor operators. The result? Masterfully clear explanations that are as enlightening as they are entertaining, often concluding with humanity’s obliteration or at least a spectacular explosion.

What If? Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions not only offers answers to never-before-addressed inquiries but also provides updated and expanded versions of the most popular answers found on the xkcd website. Here, Munroe demonstrates his extraordinary ability to break down complex scientific principles into digestible, understandable, and most importantly, amusing insights accompanied by his signature comics.

What sets Munroe’s work apart is his dedication to imparting scientific knowledge through the lens of extreme hypothetical scenarios. It’s this balance of accuracy and whimsy that makes science accessible and engaging to a broad audience. His detailed responses, grounded in factual science and mathematics, make the implausible seem plausible, and the mundane, mesmerizing.

What If? Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions is an essential read for fans of xkcd, science enthusiasts, and anyone with a curious mind who loves pondering the “what ifs” of the universe. It speaks to the child in all of us, pushing the boundaries of our imagination while grounding us in scientific truth. Teachers, students, and casual readers alike will find joy and knowledge in Munroe’s explorations, which remind us that science is not only a tool for understanding the world but also a means to marvel at its infinite wonders and possibilities.

In What If? Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions, Randall Munroe accomplishes what seems to be an impossible feat—transforming outlandish, hypothetical questions into a profound celebration of scientific curiosity. Through the pages of this book, Munroe proves that absurdity and science are not only compatible but when combined, can illuminate the beauty of questioning the world around us. Whether you’re in it for the humor, the comics, or the science, What If? Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions is a delightful read that promises to engage your mind and tickle your funny bone.

“The Victorian Internet” by Tom Standage is a compelling account that draws striking parallels between the telegraphy of the 19th century and today’s information age. At first glance, one might wonder how the bulky, paper-spewing machines of yesteryear could have anything in common with our sleek, instant messaging devices. Yet, Standage skillfully entwines the tales of past and present, illustrating that the foundations of modern electronic communication were truly laid during Victoria’s reign.

Standage’s narrative explores the telegraph as the very embodiment of a digital revolution, an innovation that condensed time and space in a way that was inconceivable in the pre-electric era. The key themes of this fascinating story center around the birth of rapid communication, the societal transformations it caused, and the lives of those who were both the agents of and witnesses to these changes. The book effectively argues that the telegraph was, perhaps, the original Internet, a comparison that has profound implications for how we understand the development and potential of our own era’s technological communication leaps.

One of the book’s most engaging aspects is its spotlight on the eclectic mix of individuals behind the telegraph. These characters, ranging from the visionary and prolific Samuel Morse to Thomas Edison, with his relentless quest for innovation, are presented with a lively depth that serves as a reminder of the human element behind technological progress. Their stories are not just of invention and discovery, but of rivalry, controversy, and the dramatic transformation of society.

The Victorian Internet is at once a history lesson and a prophetic glimpse into the future. It’s fascinating to learn how issues we consider uniquely bound to the digital age—such as concerns over privacy, hacking, and the democratization of information—were already in play over a century ago. Standage masterfully demonstrates that while the technologies may differ, human responses to technological leaps have remarkable similarities.

The storytelling approach Standage employs is both educational and entertaining. His narrative threads are laced with anecdotes, which illuminate the broader historical context and keep the reader deeply engaged. For anyone interested in the history of technology or the cultural impacts of innovation, “The Victorian Internet” functions as an enlightening mirror, reflecting the age-old patterns of society’s engagement with groundbreaking communication tools.

Tom Standage’s book is a must-read for tech enthusiasts, history buffs, and anyone curious about the lineage of contemporary communication tools. It serves as a stark reminder that the issues we grapple with today in the digital realm are just iterations of those our predecessors faced with the telegraph. “The Victorian Internet” earns a strong recommendation for its unique perspective on history, technology, and human connectivity; a reminder that though our devices may grow more complex, the essence of communication and its impact on society remains constant.

In “Galileo’s Daughter: A Historical Memoir of Science, Faith, and Love,” Dava Sobel presents readers with a compelling and intricately researched narrative that intertwines the remarkable lives of Galileo Galilei, the revolutionary scientist, and his devoted daughter, Sister Maria Celeste. Sobel, through the meticulous examination of letters and historical documents, crafts a dual biography that not only deepens our understanding of Galileo’s groundbreaking work but also paints a heartfelt portrait of a father-daughter relationship that withstood the tests of time and adversity.

At its core, “Galileo’s Daughter” explores the often tumultuous relationship between science and religion, which is as relevant today as it was in the seventeenth century. Through Galileo’s struggles and triumphs, Sobel deftly illustrates the conflict between a man’s unwavering commitment to scientific truth and the prevailing doctrines of the Catholic Church. This friction finds balance in the tender exchange of letters between Galileo and Maria Celeste, whose devout faith contrasts her father’s rational mind while also sharing his love for intellectual pursuit.

Sobel doesn’t shy away from the plague’s devastation or the impact of the Thirty Years’ War. The book captures the broader societal and political climate of the period, giving readers a total immersion into Galileo’s world. The juxtaposition of Galileo’s quest to prove heliocentrism against Maria Celeste’s cloistered life in a convent offers a poignant reflection on the delicate balance between enlightenment and belief, ambition and obligation, and the pursuit of knowledge against the backdrop of political instability and social upheaval.

Galileo’s character is brilliantly reimagined, not as the cold, distant figure carved out of historical austerity, but as a loving father and passionate inquisitor of nature’s law. Sobel’s attention to detail and her ability to translate technical scientific treatises into layman’s terms make Galileo’s discoveries accessible, allowing readers to share in his sense of wonder at the cosmos.

Perhaps the most touching result of Sobel’s research is bringing Maria Celeste to light from the shadows of history. The richness of her personality, her intellect, and her devotion to her father resonate through their correspondence. Her life serves as a counter-melody to Galileo’s public endeavors, providing an intimate look into gender roles and the limitations imposed on women of the time. Through Maria Celeste’s lens, we catch glimpses of Galileo, not as an icon of science, but as a human being fraught with concern and affection.

The power of Sobel’s writing is her ability to borrow from both historical authenticity and narrative invention to create a work that reads like a novel. Her prose is imbued with the richness and detail of an era-defining epoch, yet her meticulous research never overpowers the humanity at the story’s heart.

While the book could have veered into hagiography, Sobel maintains a critical eye, presenting Galileo with all his flaws and complexities, thus rendering him more relatable. History, through Sobel’s lens, is no mere chronicle of events but a tapestry woven with the threads of personal and philosophical conflict.

“Galileo’s Daughter” is a masterful recounting of the life of one of history’s greatest minds and his relationship with his beloved daughter, who emerged as his source of strength during his most trying times. Dava Sobel offers an insightful exploration into the intersection of faith and science—a profound and intimate narrative of human drama and scientific discovery. It is a story that transcends its historical setting to speak to the enduring struggle to understand our universe and our place within it.

In sobel’s writing, history is invigorated with emotion and intellect, making “Galileo’s Daughter” an essential read not just for aficionados of history or science, but for anyone who appreciates the complexities of the human condition. This historical memoir, while set in the distant past, echoes with timeless themes and provides a valuable perspective on the ongoing discourse between scientific progress and faith.