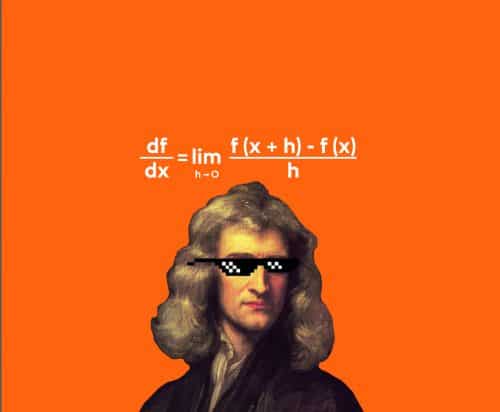

The Feynman Learning Technique is a simple way of approaching anything new you want to learn.

Why use it? Because learning doesn’t happen from skimming through a book or remembering enough to pass a test. Information is learned when you can explain it and use it in a wide variety of situations. The Feynman Technique gets more mileage from the ideas you encounter instead of rendering anything new into isolated, useless factoids.

When you really learn something, you give yourself a tool to use for the rest of your life. The more you know, the fewer surprises you will encounter, because most new things will connect to something you already understand.

Ultimately, the point of learning is to understand the world. But most of us don’t bother to deliberately learn anything. We memorize what we need to as we move through school, then forget most of it. As we continue through life, we don’t extrapolate from our experiences to broaden the applicability of our knowledge. Consequently, life kicks us in the ass time and again.

To avoid the pain of being bewildered by the unexpected, the Feynman Technique helps you turn information into knowledge that you can access as easily as a shirt in your closet.

Let’s go.

The Feynman Technique

“Any intelligent fool can make things bigger, more complex, and more violent. It takes a touch of genius—and a lot of courage—to move in the opposite direction.” —E.F. Schumacher

There are four steps to the Feynman Learning Technique, based on the method Richard Feynman originally used. We have adapted it slightly after reflecting on our own experiences using this process to learn. The steps are as follows:

- Pretend to teach a concept you want to learn about to a student in the sixth grade.

- Identify gaps in your explanation. Go back to the source material to better understand it.

- Organize and simplify.

- Transmit (optional).

Step 1: Pretend to teach it to a child or a rubber duck

Take out a blank sheet of paper. At the top, write the subject you want to learn. Now write out everything you know about the subject as if you were teaching it to a child or a rubber duck sitting on your desk. You are not teaching to your smart adult friend, but rather a child who has just enough vocabulary and attention span to understand basic concepts and relationships.

Or, for a different angle on the Feynman Technique, you could place a rubber duck on your desk and try explaining the concept to it. Software engineers sometimes tackle debugging by explaining their code, line by line, to a rubber duck. The idea is that explaining something to a silly-looking inanimate object will force you to be as simple as possible.

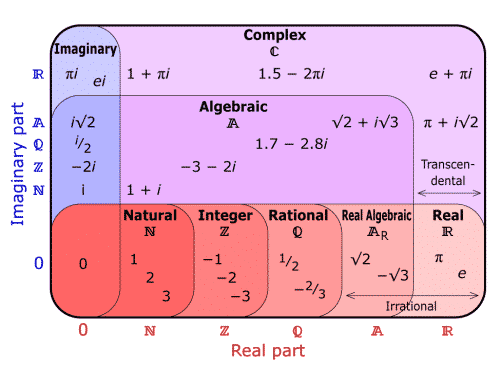

It turns out that one of the ways we mask our lack of understanding is by using complicated vocabulary and jargon. The truth is, if you can’t define the words and terms you are using, you don’t really know what you’re talking about. If you look at a painting and describe it as “abstract” because that’s what you heard in art class, you aren’t displaying any comprehension of the painting. You’re just mimicking what you’ve heard. And you haven’t learned anything. You need to make sure your explanation isn’t above, say, a sixth-grade reading level by using easily accessible words and phrases.

When you write out an idea from start to finish in simple language that a child can understand, you force yourself to understand the concept at a deeper level and simplify relationships and connections between ideas. You can better explain the why behind your description of the what.

Looking at that same painting again, you will be able to say that the painting doesn’t display buildings like the ones we look at every day. Instead it uses certain shapes and colors to depict a city landscape. You will be able to point out what these are. You will be able to engage in speculation about why the artist chose those shapes and those colors. You will be able to explain why artists sometimes do this, and you will be able to communicate what you think of the piece considering all of this. Chances are, after capturing a full explanation of the painting in the simplest possible terms that would be easily understood by a sixth-grader, you will have learned a lot about that painting and abstract art in general.

Some of capturing what you would teach will be easy. These are the places where you have a clear understanding of the subject. But you will find many places where things are much foggier.

Step 2: Identify gaps in your explanation

Areas where you struggle in Step 1 are the points where you have some gaps in your understanding.