People are looking for illumination. And many of us are looking for added time for relaxation and deep reading. Books from MIT Press seem like an attractive solution.

MIT faculty and staff have been working hard and publishing new elegant books for lifelong learners!

Is MIT Press Good?

Established in 1962, the MIT Press is one of the largest and most distinguished university presses in the world and a leading publisher of books and journals at the intersection of science, technology, art, social science, and design.

These 24 books will provide you with high-quality information! Whether you’re looking to build perfect knowledge or understand our world, put these books on your wish list. Happy reading!

By the way, you should also check out, 73 Beautiful Books from the MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series.

The Creative Brain by Anna Abraham is a thought-provoking exploration into the complexities of human intelligence and creativity, making it a fascinating read for anyone questioning the very nature of their own abilities. The author’s style is approachable, inviting readers to ponder alongside her as she tackles intricate questions of brain function and creativity. As I delved into the early chapters, I was immediately captivated by the mention of my favourite philosopher, Bertrand Russell. His words resonate deeply with the human condition—highlighting how we often cling to beliefs that align with our instincts, a theme woven throughout the book.

One of the most compelling sections is titled “The Left Brain Versus the Right Brain,” where Abraham begins to unravel the mysteries behind the differences between individuals like my brother and me. This part echoed my lifelong wonderings about our varying strengths and weaknesses, particularly in mathematical versus social intelligence. Perhaps the most enlightening aspect for me was the discussion on the role of the Dopamine hormone in sparking creativity.

In a world saturated with diverse opinions, understanding how our brains generate ideas becomes crucial. Abraham’s insights lead readers to a greater appreciation of their own cognitive processes, urging us to think about not just what we feel and believe but also why we feel and believe it. This connection prompts a profound inquiry: If we learn to harness our brain’s potential better, might we unlock doors to capabilities we have yet to explore? In essence, The Creative Brain serves as both a guide and a reminder that knowledge about our own minds can lead to more effective and creative thinking in our everyday lives.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become an integral part of many industries, thanks to the advancements in machine learning and deep learning technologies. While AI may seem complicated and overwhelming to many, there is a non-technical book that offers a quick and enjoyable way to learn about these complex technologies – “How Smart Machines Think” by Sean Gerrish.

As an AI enthusiast, Sean Gerrish wrote “How Smart Machines Think” with the objective of making the book accessible to a broad audience without using too much technical jargon. His intention was to create a book that even decision-makers evaluating AI for their companies and individuals interested in transitioning into data science could quickly understand.

How Smart Machines Think explores the world of AI from various angles and includes stories of breakthroughs and examples of how AI is used in our daily lives, such as TV shows, video games, and self-driving cars. It takes the reader beyond the surface level and delves into more serious applications of AI, such as robotics in manufacturing and smart healthcare.

One of the most significant benefits of this book is that it is easy to read and understand. The author uses storytelling and simple language to explain complex concepts, making it a fun and engaging read. The book also contains a wealth of references and links to resources that readers can use to further their understanding of the topics.

“How Smart Machines Think” provides a comprehensive overview of AI and offers insights that can be valuable to both novice and experienced readers. It not only covers the basics but also dives into more complex topics such as neural networks, deep learning, and computer vision. With the rapid pace of technology and the ever-growing use of AI, the book is a must-read for anyone looking to stay relevant in their industry.

In conclusion, “How Smart Machines Think” by Sean Gerrish is an excellent book for anyone looking to learn about artificial intelligence. It offers a comprehensive understanding of AI, machine learning, and deep learning technologies in a non-technical yet engaging manner. It is an eye-opener for decision-makers evaluating AI for their companies and individuals interested in transitioning into data science. I highly recommend this book as a valuable source of knowledge in the constantly evolving world of AI.

In the realm of physics and beyond, Richard Feynman’s name resonates as a symbol of brilliance, wit, and an unrivaled capacity to unveil the mysteries of the universe in an engaging, accessible manner. “The Character of Physical Law” based on Feynman’s series of Messenger Lectures given at Cornell in 1964 and first published in 1967, embodies these traits and offers a glimpse into the mind of one of the twentieth century’s most influential physicists.

At its core, this book is not just an exploration of physical laws but a testament to Feynman’s belief in the beauty and order of the universe. Through his perspective, physics becomes less about the human triumph of discovering these laws and more about the elegance with which nature itself adheres to them. It’s this humility and sense of wonder that make “The Character of Physical Law” significant and enduring.

Feynman‘s approach to discussing topics such as the role of mathematics in physics, the principle of conservation, and the enigma of symmetry is refreshingly candid and filled with personality. His prose is neither burdened by jargon nor oversimplified to the point of dilution; instead, Feynman strikes a balance that captures the complexity of physics while remaining comprehensible to those outside the scientific community.

One of the book’s strengths lies in its examination of the process of scientific discovery itself. Feynman demystifies this process, presenting it not as a series of eureka moments but as a careful, ongoing conversation between hypothesis and experiment. It is here that the reader can truly appreciate the scientific mindset—driven by curiosity, tempered by skepticism, and always subject to the immutable laws of nature.

Frank Wilczek’s foreword in later editions accentuates the timeless relevance of Feynman’s discussions, despite advancements in physics that have occurred since the original publication. This gesture acknowledges both the progress science has made and the foundational truths that “The Character of Physical Law” communicates.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this book is how Feynman’s enthusiasm for physics transcends the printed page, inviting readers to share in his fascination. This is no small feat considering the often abstract and counterintuitive realms of modern physics he navigates.

In essence, “The Character of Physical Law” is a potent reminder that the pursuit of knowledge is not about asserting human dominance over nature but about striving to understand the world on its own terms. Feynman, through his insight and unparalleled ability to communicate, offers not just a book on physics but a philosophical inquiry into the heart of scientific inquiry.

For those looking to immerse themselves in the thoughts of a Nobel laureate who could speak of complex principles with the ease of conversation, “The Character of Physical Law” is an essential read. Beyond its scientific import, it serves as a beacon for the notion that at the intersection of curiosity and discipline lies the blueprint for discovery.

How to Stay Smart in a Smart World? According to the doomsday prophets of technology, robots will one day rule the globe, leaving humans in their dust. While supporters of the tech business believe that replacing people with software could make the world a better place, tech industry critics warn of the potentially negative effects of surveillance capitalism. They are unanimous in their prediction that, in the not-too-distant future, machines will outperform humans in every aspect of human activity. Gerd Gigerenzer demonstrates why this is not the case in his book How to Stay Smart in a Smart World, in which he also instructs us on maintaining our agency in a world dominated by computer programs.

There are some tasks, such as playing chess, that are beyond the capabilities of machines powered by artificial intelligence (life-and-death decisions or anything involving uncertainty). Gigerenzer explains why algorithms frequently fail at finding us romantic partners (because love is not a game of chess), why self-driving cars fall prey to the Russian Tank Fallacy, and how judges and police are increasingly relying on nontransparent “black box” algorithms to predict whether a criminal defendant will re-offend or show up in court. He refers to Black Mirror, discusses the dilemma of privacy (people want privacy but give away their data), and describes how social media hooks us by intermittent programming reinforcement in the form of the “like” button. All of these ideas are related to the paradox of privacy. Gigerenzer reminds us that we shouldn’t blindly fear or trust intelligent technology but shouldn’t distrust it without giving it due consideration.

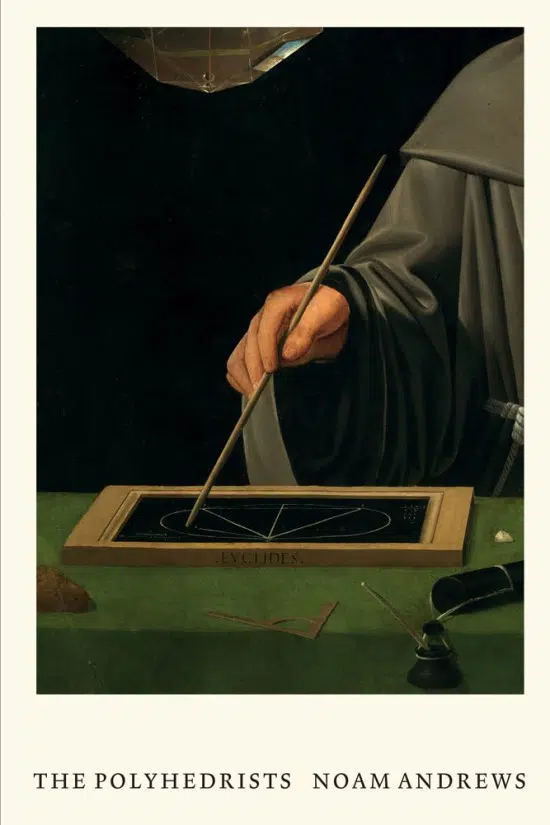

The sixteenth century was a time of immense change and progress in Europe. Think of the groundbreaking discoveries by Copernicus and the bravery of Martin Luther in his fight against the Catholic Church. This era also saw painters using perspective to create a sense of depth in their artwork and the impact of printing on the spread of knowledge after Gutenberg’s invention of movable type.

During the late fifteenth century, wealthy and educated individuals began collecting and assembling classical texts on mathematics and astronomy. Regiomontanus, a renowned astronomer and mathematician, moved to Nuremberg and established an observatory and printing press. Although he died before his vision could be fully realized, his work marked the beginning of a mathematical rebirth.

The Polyhedrists, based on Andrews’s Harvard thesis, provides valuable insight into the tumultuous sixteenth century through the lens of polyhedra. These geometric shapes served as a bridge between the academic world of mathematics and the practical world of artists and craftsmen. The Polyhedrists is richly illustrated and offers a feast for the eyes. We meet talented artisans and gain a deeper understanding of their craft.

The most famous polyhedra are the five regular solids, known as Platonic solids after their description in Plato’s Timaeus. These shapes are associated with the classical elements and the ethereal universe. Additionally, there are thirteen semi-regular or Archimedean solids credited to Archimedes. Their journey to Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries remains a mystery.

A significant figure in this narrative is Albrecht Dürer, an artist from Nuremberg. Despite lacking a classical education, Dürer’s friendship with the well-connected Willibald Pirckheimer allowed him access to Latin Euclid. He later published a book that provided artists with practical methods for creating precise drawings using ruler and compass. Dürer’s work became a vital link between academia and the world of artisans.

While The Polyhedrists largely provides accurate historical information, there are occasional inaccuracies. The author mistakenly attributes the invention of diagrams in Euclid’s Elements, when they were already present in earlier manuscripts. These diagrams were essential for understanding the text and were not added to improve sales. This distinction should be applied to Luca Pacioli, who enlisted Leonardo da Vinci to illustrate his book.

In conclusion, The Polyhedrists offers a captivating exploration of the interplay between art, mathematics, and society during the sixteenth century. The Polyhedrists serves as a valuable resource for anyone interested in the cultural and intellectual shifts of this era.

A fundamentally new style of thinking is required to tackle today’s difficult problems; this new way of thinking integrates art, technology, and science to boost human creativity and understanding. Future innovators will need to be able to balance their creativity and execution skills, as well as manage complicated issues like pandemics and climate change. The Nexus is the location of this convergence. Julio Mario Ottino and Bruce Mau provide a roadmap for traversing the nexuses of art, technology, and science in this thought-provoking and aesthetically stunning book.

The Nexus combines words and pictures to equip us—both as individuals and as organizations—ready for the opportunities and challenges of the twenty-first century. From the Renaissance, when the domains were one, to the twentieth century, with strong, collaborative creative outpourings from locations as dissimilar as the Bauhaus and Bell Labs, compelling historical examples explain the present. Leaders must be able to understand simplicity in complexity and complexity in simplicity. They must also embrace the potent concept of complementarity, which allows opposing extremes to coexist while expanding our understanding. More than managing is needed for innovation. Leaders create compasses; managers use maps.”

The wavelength theory of light and color was well-established by the time Goethe’s Theory of Colors was published in 1810. In Goethe’s opinion, the hypothesis came forth as a result of mistaking an incidental result for an essential concept. He maintained that knowledge of physics made comprehension more difficult than just seeming to have it. He only drew his conclusions from a careful personal examination of the phenomena of color.

Goethe expressed his utmost confidence in his own theory, saying: “From the philosopher, we believe we merit thanks for having traced the phenomena of colors to their primary sources, to the conditions under which they appear and are, and beyond which no further explanation regarding them is possible.”

The intelligent reader of today may enjoy this work for entirely different reasons, such as the beauty and scope of his hypotheses regarding the relationship between color and philosophical ideas, for an insight into early nineteenth-century beliefs and modes of thought, and for the flavor of life in Europe just after the American and French Revolutions. Of course, Goethe’s scientific conclusions have long since been thoroughly disproved.

It is not necessary to study the book in order to enjoy it. Goethe can most effectively discuss color harmony and aesthetics thanks to his subjective theory of colors. These ideas will elicit a favorable reaction from some readers due to their strengths. Others might consider them to be pure imagination, but they appreciate the elegance and flair of their presentation.

The work can also be interpreted as a reliable manual for the investigation of color phenomena. Although Goethe’s findings have been disproved, no one disputes his account of the observable events. The reader will be guided through a demonstration course using basic objects like containers, prisms, lenses, and the like that will cover both subjectively created colors and the physically detectable aspects of color. By carefully reading Goethe’s descriptions of color phenomena, the reader may become so cut off from the wavelength theory—Goethe never once brings it up—that he may start to think about color theory comparatively free of prejudice, whether old or new.”

An introduction to the practice of proofreading is provided in this book. Leading research mathematician author provides a number of innovative and appealing mathematical claims with simple but intriguing proofs. Number theory, combinatorics, graph theory, game theory, geometry, infinity, order theory, and real analysis are only a few of the subjects covered by these arguments. The intention is to instruct students and aspiring mathematicians in the art of elegant and precise proof-writing.

“Many members of the public were first introduced to “metadata” when it first appeared in reports regarding spying by the National Security Agency and quickly rose to the status of breaking news. Should people be comfortable that the NSA was “just” gathering metadata—information on the caller, recipient, time, duration, and location—and not actual recordings of the conversations—about phone calls? Or does metadata from phone calls disclose more than first appears? Jeffrey Pomerantz provides a clear and understandable introduction to metadata in this book.

Metadata has evolved into infrastructure in the age of ubiquitous computing, just as the electricity grid or the road network. Every day, we produce it or engage with it. Pomerantz explains that it is not merely “data about data.” It is a technique for reducing the complexity of a thing to a simpler version. As an illustration, a book’s title, author, and cover image are all examples of metadata. If metadata accomplishes its job successfully, it blends into the background and is taken for granted by everyone (perhaps with the exception of the NSA).

Pomerantz defines metadata and discusses its purpose. He makes a distinction between many kinds of metadata, including descriptive, administrative, structural, preservation, and use, and looks at various users and uses for each category. He talks about the technology that enables contemporary metadata and makes predictions regarding metadata’s future. Readers will become accustomed to seeing metadata by the end of the book. Pomerantz cautions us that this is the universe of metadata, and we are merely a part of it.”

“We are surrounded with imagery, some of it voluntarily and most of it not. Everything we see in this visual environment—color, the moon, a skyscraper, a stop sign, a political poster, rising sea levels, or a picture of Kim Kardashian West—somehow becomes readable, commonplace, and approachable. What causes this to occur? How do we function in our visual surroundings? This book from the Essential Knowledge series from the MIT Press provides a road map for navigating the complexity of visual culture by presenting methods for pondering what it means to gaze and see—and what is at stake in doing so.

It has always been the dominant and the dominant that have shaped visual culture. This book offers ideas for using the visual as a weapon to promote change that brings people together. Alexis Boylan investigates how we interact with and are controlled by what we see using historical and modern examples, such as Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, Beyoncé, and Jay-Z visiting the Louvre, and the first photos of a black hole. She starts off by asking: What are visual culture, and what issues, concepts, and conundrums drive our approach to the visual? She then asks, “Where are we permitted to see it, and where are we standing while we look”? Who then: whose bodies have been in or not in visual culture, and who is permitted to view it? Finally, at what point does the visual become independent of time? When do we get the information we require?”