Have you ever considered learning how to think mathematically? Using math proofs requires logical reasoning, problem-solving skills, and the ability to make connections between concepts. By reading math books to learn mathematical proofs, you can unlock the power of this type of thinking and gain valuable insight into a variety of topics. Below, you will find 70 best math books to learn mathematical proofs.

The Benefits of Learning Math Proofs

Math proofs are used in various fields, such as engineering, economics, computer science, physics, and mathematics. Learning to think mathematically will benefit your studies in these fields and give you an edge in other aspects of life, such as problem-solving, decision-making, and critical thinking. Mathematical proofs provide a systematic way to analyze problems so that you can come up with solutions quickly and accurately.

Math Books to Learn Mathematical Proofs

Math books are essential if you want to learn mathematical proof. These books provide an easy-to-understand approach to understanding the fundamentals behind math proofs. They often include step-by-step instructions on how to solve problems as well as visual demonstrations of how these concepts work together. Reading these books is key to developing your skills in mathematical proof because they provide an accessible entry point into more advanced topics like abstract algebra or number theory.

While math books are great for getting started with learning mathematical proof, they have their limitations when it comes to tackling more complex problems. As you progress further down the road with studying math proofs, you must supplement your knowledge with online resources such as YouTube tutorials or online courses that give you a more comprehensive overview of various areas within mathematics.

Additionally, engaging in practice questions can help solidify your understanding and hone your skills when it comes to using logic and reasoning for problem-solving.

Mathematical proof is an invaluable skill that can be applied across multiple fields. It provides a framework for analyzing problems while helping develop your problem-solving abilities and critical thinking skills, which are transferable across many different domains in life. To get started with learning math proof, reading math books is essential as they provide an easy-to-understand introduction to this field while giving step-by-step instructions on how to solve various types of problems. However, as one progresses further into this area, more advanced resources should be utilized, such as online tutorials or courses along with practice questions which will help hone one’s understanding and application within this area even further!

Below, you can find 70 best math books to learn mathematical proofs. If you enjoy this book list, you should also check 30 Best Math Books to Learn Advanced Mathematics for Self-Learners.

Before I get started, I would like to suggest Audible for those of us who are not the best at reading. Whether you are commuting to work, driving, or simply doing dishes at home, you can listen to these books at any time through Audible.

Some books turn on a little experiment bulb in your head the moment you read their title. “Why cats land on their feet?” sounds simple enough — but it’s actually a philosophical trap. You think you know the answer, but you really don’t. Mark Levi lives in that gray area — where the seriousness of physics meets childlike curiosity.

This book is made up of 77 small paradoxes. But not the kind you flip through over coffee. Some are so technical that if you start with just high-school physics, you might crash and burn by page ten. Levi’s goal isn’t to intimidate you with formulas; it’s to push you into that delightful moment of “Wait, have I been wrong about this all along?”

For example, he asks what happens when two astronauts, floating in zero gravity, push a helium balloon toward each other. Does the capsule move? The balloon? The universe? On another page, he explains how to remove a cork from a wine bottle by hitting it against a wall with a book — complete with the physics behind it. Reading these parts feels like flipping through the back pages of an old Popular Science magazine from the 1980s.

But not every chapter is that fun. Some sections really do feel like engineering lecture notes. When Levi says, “Just think of it this way,” you might still be stuck wondering, “Wait, who was Bernoulli again?” So yes, this book both delights you and pokes you with a mild existential reminder: “Maybe I don’t know as much as I thought I did.”

Still, Levi’s gift is keeping the spirit of “why does this happen?” alive. Why can a child get a swing moving without touching the ground? The answer lies in that elusive “energy transfer” teachers always talk about — and Levi manages to explain it as if Newton himself were sitting on the swing, testing his own laws.

The book ends with an appendix — a mini physics glossary that runs from Newton’s laws to the basics of calculus. Reading it feels like realizing that every “weird little thing” you just learned actually has a solid foundation.

Mark Levi’s Why Cats Land on Their Feet is a strange little alley where scientific wisdom and childlike wonder meet. Each corner hides an experiment that flips your expectations, each page offers a small “aha!” moment. But fair warning: if you plan to relax with this book, bring not just a cup of coffee but also a notebook — and patience.

This book isn’t about the dullness of physics — it’s about its wonder. You don’t just learn why cats land on their feet; you start noticing the ground beneath your own a little differently.

That’s why reading Mark Levi makes you feel a bit like a cat and a scientist at once — always curious, always falling, and somehow, always landing on your feet.

Hold on a second. Mathematics. Logic. When we combine those two in the same sentence, let alone the same phrase, I can almost feel some of your brain cells saying, “Alright, I’m heading out,” and going on vacation. “Mathematical Logic” sounds like a topic whispered about only by ultra-intelligent people living in ivory towers, a subject whose name alone requires three doctoral theses, right?

I used to think so, too. That was until I stumbled upon this small, unassuming, but surprisingly packed book on one of the universe’s dusty shelves: “What is Mathematical Logic?”. This book was written by a group of authors (C. J. Ash, J. N. Crossley, et al.) with names as intimidating as the subject itself. But when you open the cover, you’re not greeted by a professor’s boring lecture notes, but by a conversation that feels like a smart, funny friend saying, “Hey, come over here and let me explain this thing my way.”

The book doesn’t just dive in with, “Okay, now divide formula A by B.” Instead, we travel back in time. On one side, there’s a path starting with the formal deductions of Aristotle and Euclid, like, “If all men are mortal, and Socrates is a man, then Socrates is probably not going to turn into a potato.” On the other side, there’s a more “number-crunching” trail followed by guys like Archimedes, who used mathematics to understand the universe.

For centuries, these two paths went their own ways, unaware of each other. One was busy with the “art of correct thinking,” while the other explored the mysterious world of numbers and shapes. Then, in the 17th century, Newton and Leibniz entered the scene and, with a magic wand called “calculus,” merged these two paths. That was the beginning of the romantic comedy where math and logic asked, “Hey, maybe we work better together?”

The book narrates this historical journey so fluently that one moment you find yourself in Ancient Greece, wearing a toga and debating philosophy, and the next, you’re having coffee with a periwigged mathematician.

Now for the real question: do you really need to be a math genius to understand this book? Honest answer: No, but a little background definitely helps. The author doesn’t just throw you into the deepest part of the ocean. They let you roll up your pants, step into the water, and get used to the temperature first.

And that’s the beauty of this book. Instead of proving everything from the ground up, it explains the “why” behind the big ideas. Take, for example, the famous Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem. In essence, this theorem states that within any mathematical system, there will always be statements that are “true but unprovable.”

This is a mind-bending idea. It’s as if the architect of the universe winks at you and says, “You thought you could solve all the secrets? Sweet dreams.” The book breaks down this colossal idea into digestible pieces using tools like Turing machines (the imaginary ancestors of modern computers) and recursive functions. It doesn’t teach you how to build a Turing machine (thankfully), but it explains what a Turing machine does and what that has to do with logic, often through a metaphor.

Think of it this way: You have the world’s most advanced cookbook. You can make any dish. But could that book contain a chapter titled “A Recipe for a Dish That Cannot Be Made with the Recipes in This Book“? No, because if it did, it would have been made! Gödel’s theorem is a bit like that. Mathematics defines its own limits from within.

If you absolutely hate math and numbers give you an allergic reaction, this book will probably just collect dust on your nightstand. But:

- If you’re curious about how mathematics is not just about numbers, but actually a “way of thinking,”

- If you’re a coder who wonders, “Where do the roots of this ‘logic’ thing really come from?”

- Or if you’re just looking for an intellectual adventure that will stretch your mind without overwhelming you,

…then “What is Mathematical Logic?” is for you.

This book isn’t a textbook; it’s more of a guide, a tour guide. It stops you in front of the great monuments of mathematical logic (the Gödel-Henkin Completeness Theorem, Model Theory, Set Theory, etc.), tells you how impressive they are, and then says, “If you want, you can check out more detailed books to explore inside, but for now, just enjoy the view.”

Ultimately, What is Mathematical Logic? takes a frightening beast like mathematical logic, tames it, and lets you play with it. You might not be able to fully train it, but at least you won’t have to be afraid of it anymore. And that, in itself, is a major victory.

Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon is one of the cornerstones of modern science fiction. When it was first published in 1865, the dream of reaching the Moon was still a fantasy, yet Verne tackled it with both technical precision and biting satire. This special 100th Anniversary Collection doesn’t just preserve the text—it transforms it into a visual experience. With illustrations originally published in 1874, the reader can see Verne’s vision come alive: the colossal cannon, the meticulous engineering plans, and the fiery enthusiasm of his characters.

The story begins with the members of the Baltimore Gun Club, bored in the aftermath of the Civil War, looking for a new challenge. Their solution is as simple as it is audacious: go to the Moon! Led by President Impey Barbicane, they propose building an enormous cannon to launch a projectile into space. What follows is a mix of rivalry (between Barbicane and Captain Nicholl), the dramatic arrival of French adventurer Michel Ardan, and a world captivated by the project. Verne doesn’t shy away from detail: pages of calculations, physics explanations, and financial logistics make the narrative sometimes feel like a scientific treatise. Yet these technical digressions give the novel its uncanny sense of plausibility.

For contemporary readers, the book’s most fascinating feature is its striking similarity to real history. Apollo 11’s 1969 journey mirrors Verne’s vision in eerie ways: a three-person crew, a launch from Florida, a module named Columbia. Even Verne’s imagined scene of Americans planting their flag on the lunar surface foreshadows one of the most iconic television moments of the 20th century.

What makes this illustrated edition special is its period artwork. The 19th-century illustrations not only enhance Verne’s descriptions but also allow modern readers to glimpse the awe and ambition of his era. It’s both a collector’s item and a gateway for younger readers curious about the origins of space travel in literature.

Of course, the book isn’t paced like modern sci-fi. Long sections about materials, costs, and projectile trajectories may feel slow today. But Verne wasn’t just spinning fantasies—he was building them step by step, showing how imagination and science could merge. That’s why the book remains more than a curiosity: it’s a visionary work that asks, “What if?” rather than merely entertaining with the impossible.

In short, From the Earth to the Moon is as witty as it is ambitious, as satirical as it is scientific. This Illustrated 1874 Edition: 100th Anniversary Collection honors Verne’s genius and highlights the uncanny way fiction sometimes becomes reality. It’s a book worth having in any library—not just as a classic adventure, but as a testament to how far human imagination can reach.

First published in 1687, The Principia is one of the most influential works in the history of science, laying the mathematical foundation for classical mechanics and transforming the way humanity understands motion, gravity, and the physical universe. Written in Latin, the Principia presents Newton’s three laws of motion and his law of universal gravitation, all derived using a geometric form of reasoning rather than modern calculus notation—although the underlying methods were deeply tied to the new mathematics Newton had developed.

Across its three books, Newton builds a complete system of the world: from the motion of objects on Earth to the trajectories of planets and comets. The Principia is not an easy read for the modern audience—it blends dense geometry, philosophical argumentation, and experimental evidence—but its intellectual power is undeniable. Reading it today offers a glimpse into the birth of modern science and the way Newton fused mathematics with empirical observation to uncover universal laws.

Its inclusion in this free calculus books list may seem surprising at first, but the Principia is a key historical bridge between early modern mathematics and the systematic application of calculus to physical phenomena. For anyone interested in the roots of mathematical physics, it remains an unparalleled source.

📖 Read for Free: Principia Mathematica – Full Text (English Translation)

📚 Print Edition: Get it on Amazon

Some books don’t just tell a story—they offer an experience. Counting Creatures is exactly that kind of book. With Julia Donaldson’s elegant rhymes and Sharon King-Chai’s mesmerizing illustrations, it becomes something magical—not just for kids, but for adults too.

It begins with a bat and her single pup. Then with each turn of the page, the number of babies grows: 2 lambs, 3 owlets, 4 fox cubs… up to 10. But it doesn’t stop there. The numbers keep going, introducing a delightful mix of animals—ducklings, mice, hares, spiders—each page doubling as a mini lesson in nature. It’s not just about counting; you also learn the proper names for baby animals, like “leveret” for a baby hare. Even adults might discover something new here.

The lift-the-flap elements aren’t just gimmicks. They’re designed to be part of the story—sometimes they’re leaves, sometimes rocks or tails, sometimes entire environments. Some flaps open upward, others sideways. Every page feels like a surprise waiting to be revealed, almost like a mini paper engineering marvel.

Visually, the book is breathtaking. Rich, vibrant colors and intricate die-cuts turn every page into something frame-worthy. Especially the spider pages—so detailed you’ll be tempted to go back and count every last one (and yes, even though the cover says 30, you might find 32).

The language flows beautifully. The rhymes are rhythmic, memorable, and fun, making it easy for young readers to pick up on patterns and repeat them aloud. The repetition turns reading into an almost musical experience—one that kids will want to revisit again and again.

There’s even a surprise at the end—a search-and-find puzzle that invites readers to flip back through the book and look more closely. It adds an extra layer of fun and engagement, making it more than just a one-time read.

One small caveat: some of the flaps and pages are delicate. They might not hold up well in busy library settings. But for home reading, especially as a shared experience between child and adult? Absolutely worth it.

Counting Creatures transforms counting into a journey—through animals, habitats, language, and wonder. It’s educational for kids and inspiring for grown-ups. The kind of book that belongs not on a shelf, but right out on the coffee table.

And here’s a tip: don’t miss the wonderful conversations this book can spark with your child. A book like this is a perfect beginning.

Significant Figures: The Lives and Work of Great Mathematicians

Ian Stewart’s “Significant Figures” aims to introduce us to the lives and work of 25 of history’s most important mathematicians, showing how their discoveries built the mathematics we use today. From Archimedes to William Thurston, the book offers a historical sweep, even including figures sometimes overlooked, like Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi and Ada Lovelace. But does it hit the mark for everyone?

What the Book Does Well:

- Humanizing the Geniuses: One of the strongest points, highlighted by many readers, is how the book brings mathematicians to life. Stewart explores their “colourful lives beyond their work,” giving us a sense of their unique personalities, family backgrounds, and social environments. This makes the often-abstract world of mathematics feel more relatable and less intimidating. Readers enjoyed learning about figures like Cardano and Alan Turing, with one anecdote describing Turing’s bicycle chain problem and how he found a mathematical solution.

- A Historical Perspective: The book offers a chronological history of mathematics, allowing readers to gain insight into how concepts developed over time. Stewart is praised for connecting the work of different figures, illustrating that great discoveries rarely appear out of nowhere but are built on centuries of effort by many people from various cultures. It provides a valuable “mid-level” overview of mathematical concepts.

- Highlighting Inclusivity (to an extent): The author makes an effort to include diverse figures, touching on non-Eurocentric perspectives and addressing the struggles women faced in the field. For example, the book discusses Emmy Noether’s theorem and how she fought against barriers to teach mathematics as a professor.

- Stewart’s Passion: Many reviewers noted that Stewart’s love for mathematics “drips off every page”. His enthusiasm is contagious, making even complex ideas feel fascinating, and his writing is often described as clear and fluid.

Where It Might Get Tricky (Points for Consideration):

- The Math Itself: This is where opinions diverge. While Stewart tries to make mathematical achievements approachable for non-mathematicians, many readers found the explanations could still be quite dense or use terminology not commonly understood without explanation. Some felt there wasn’t enough in-depth explanation to truly learn a concept, yet too much detail for a casual read. If you have little to no mathematical background, you might find yourself “awash at sea,” especially as the book moves into more advanced topics from the 20th century. As one reader put it, you “should be fine” if you understand the pun in the title, implying a certain level of mathematical tolerance is needed.

- Audiobook Format: A significant number of audiobook listeners struggled with the mathematical formulas and concepts being described verbally. If you’re a visual learner, reading the physical book is likely a better option to grasp the mathematics.

- Scope and Selection: With only 25 mathematicians covered in 280 pages, each individual gets about 10 pages. This means the coverage of their lives and work is brief, serving more as an introduction than an in-depth biography. Some reviewers felt certain prominent mathematicians, like Laplace, Pascal, Leibniz, or Euclid, were notably absent. There was also some debate about the inclusion of certain figures, such as Ada Lovelace, with one reviewer suggesting there was “absolutely nothing in this entry to suggest that King was in any sense a ‘trailblazing mathematician'”.

Who Is This Book For?

“Significant Figures” is perhaps best suited for those who already have a degree of tolerance for mathematical terminology and exposition, or scientists who use mathematicians’ work without knowing much about the person behind it. It serves as a great “appetizer” or an engaging introduction to further research for those interested in the human stories behind mathematical breakthroughs. If you’re looking for a deep dive into specific mathematical theories or a beginner’s guide to core concepts, this might not be the primary resource, but it could certainly spark your curiosity to learn more.

In conclusion, Ian Stewart’s “Significant Figures” is a lively and enjoyable read that provides a valuable historical overview and humanizes the often-abstract world of mathematics. While its success in explaining complex math to a general audience is mixed, it excels at telling compelling stories and inspiring curiosity about the brilliant minds who shaped our understanding of the universe.

Have you ever thought about someone who was obsessed with something to a degree that it felt like a black hole, not just a mere fixation? Well, Wilson A. Bentley’s case wasn’t just an obsession; it was a gravitational pull of dedication! Duncan C. Blanchard’s book, “The Snowflake Man: A Biography of Wilson A. Bentley“, tells the captivating story of this remarkable individual.

The Genesis of “Snowflake Bentley”: A Farmer’s Singular Obsession

Let’s dive into who this Snowflake Bentley was. On paper, he was a farmer from Jericho, Vermont. But when asked for his occupation, he’d confidently state, “Snowflakes“! This single detail tells you everything about the man. From his teens, Snowflake Bentley taught himself how to photograph snow crystals through a microscope. He then pursued this lifelong obsession with snowflakes and their beauty for years before the scientific value of his work was recognized. Over his lifetime, Snowflake Bentley took more than five thousand photomicrographs of ice, dew, frost, and especially snow crystals. His ultimate dream was to find “the one, or the few, preeminently beautiful snow crystals”.

The Unconventional Genius of “Snowflake Bentley”

The Snowflake Man came from a poor farming background and had no formal scientific training. Because of this, some of his theories about snowflake formation were occasionally misconceived. Despite these challenges, he made a substantial contribution to the scientific understanding of snow. He was a true pioneer of snowflake photography, considered a genius and a man ahead of his time. His neighbors found him a bit “weird”, or as one source put it, “a bit cracked”, but perhaps not wealthy enough to be labeled “eccentric”. He even built his photographic equipment by hand as a teenager, incorporating found materials like broom straws.

“The Snowflake Man”: Poet of the Ephemeral

Beyond his scientific pursuits, Snowflake Bentley also possessed a profound appreciation for the abstract beauty of nature. He didn’t take an interest in religion, yet he combined pragmatic scientific observation with mysticism in a charming and unusual fashion. Snowflake Bentley wasn’t just observing; he was also philosophizing. He wrote, for instance, that “The snow crystals… come to us not only to reveal the wondrous beauty of the minute in Nature, but to teach us that all earthly beauty is transient and must soon fade away. But although the beauty of the snow is evanescent, like the beauty of the autumn, as of the evening sky, it fades but to come again”. This highlights Snowflake Bentley’s unique blend of scientific rigor and poetic sensibility.

Duncan C. Blanchard’s Lens on “Snowflake Bentley”

Duncan C. Blanchard’s biography, “The Snowflake Man“, provides an excellent look into the life of Snowflake Bentley. Blanchard, being a meteorologist and physicist himself, clearly knows his subject matter well and was likely inspired by Snowflake Bentley’s unwavering dedication. The book’s research is impressive, drawing from personal interviews, unpublished documents, and various articles, making it the most extensive record of Bentley’s life and work.

Blanchard skillfully balances discussions of snowflake observation science with personal details that bring Snowflake Bentley to life. He portrays a man with a distinct Northern New England quirkiness, who was mild-mannered, perhaps shy, enjoyed practical jokes, and was a musician. Anecdotes, letters, and quotes from Snowflake Bentley’s own writings are included, such as his performing piano for audiences while a family friend sang during the intermission of his slide shows. The writing style is methodical, and though the book is a “slim effort” that can be read in one sitting, it effectively captures both the scientist and the man. It also provides satisfactory context for Snowflake Bentley’s beautiful photographs.

The Enduring Legacy of “Snowflake Bentley’s” Obsession

Ultimately, the Snowflake Man is more than just a biography of a snow crystal photographer. It’s a fitting tribute to one man’s lifelong obsession, a testament to dedication, and a story of contributing to science despite prevailing prejudices. Snowflake Bentley’s unprecedented collection of thousands of photographs taught the world just how unique these ice crystals truly are.

The most compelling aspect of the book is the insight it offers into obsession itself, which will linger long after you turn the last page. It’s a worthy and recommended read if only to honor the fierce, undying commitment of the Snowflake Man. If you’re interested in meteorology, photography, or simply the beauty of nature, the story of Snowflake Bentley’s life will undoubtedly resonate with you. You’ll come away with a lesson in singular dedication that lasts longer than most things you’ve recently encountered.

Alright, buckle up, because we’re about to dive into the mind of a guy who was, by all accounts, so unbelievably brilliant and simultaneously so unbelievably weird that people called him “the strangest man”. We’re talking about Paul Dirac, the British physicist who, if you haven’t heard his name alongside Einstein or Newton, you absolutely should have. And Graham Farmelo’s “The Strangest Man: The Hidden Life of Paul Dirac, Mystic of the Atom“ is here to explain why.

First off, let’s get the core deal with Dirac. This dude was a pioneer of quantum mechanics, snagged a Nobel Prize for Physics (the youngest theoretician ever to do so, mind you), and basically reshaped our understanding of the universe. Michael Frayn even called the book “a monumental achievement – one of the great scientific biographies”. Pretty high praise.

But here’s where the “Strangest Man” part really kicks in:

The Man Himself: A Human Robot with a Hidden Heart?

Imagine a genius so pathologically reticent that his postcards home were only about the weather. Yeah, that was Dirac. He was described as strangely literal-minded, legendarily unable to communicate or empathize, and a loner. Reviewers throw around terms like “bona fide eccentric,” “nerd,” “geek,” and “social misfit”. One even suggested he had “the emotional depth of a carrot”. Ouch.

Part of this seems to stem from a pretty brutal childhood. His very strict father would single out young Paul for one-on-one suppers where they only spoke French. Dirac deeply resented this and blamed those “excruciating evenings” for his extreme reticence, even vowing never to speak French again as an adult. This tough upbringing seemingly molded him into the “introverted master of clear thought” he became.

Despite all this, there’s a softer side. He showed loyalty to his family and friends and apparently cried when Einstein died, not because he lost a friend, but because “science had lost an invaluable scientist”. He also had a soft spot for Disney classic movies and “Odyssey 2001“. See? Not all circuits and no soul.

The Brain Power: Pulling Reality Out of Thin Air (with Math)

Now, for the mind-blowing stuff he actually did.

- Antimatter, Baby! Dirac’s greatest triumph was hypothesizing the existence of antimatter (the positron). Get this: he didn’t look at any experimental data. He just “messed around with the equations for the electron”, found a “beautiful and elegant” way to manipulate them, and voilà, predicted a particle that was like an electron but “opposite in nature”. Less than five years later, experimentalists found it. This prediction was “motivated solely by faith in pure theory, without any hint from data”. That’s like predicting a whole new species of animal just by looking at a blueprint of existing animals and realizing the blueprint implies something else must be there. Wild.

- Quantum Everything: He played a major role in establishing quantum mechanics and was a pioneer of Quantum Field Theory (QFT) and Quantum Electrodynamics (QED). His work on magnetic monopoles even became some of the basis for string theory.

- The Textbook that Wouldn’t Die: His quantum mechanics textbook, written in 1930, is still in print and used as a standard today. When Albert Einstein himself admitted he had problems following some of Dirac’s equations, and he was called the “greatest English physicist since Isaac Newton“, you know you’re dealing with someone operating on a different plane.

Dirac’s secret sauce? A unique blend of “part theoretical physicist, part pure mathematician, part engineer“. His engineering training gave him a visual thinking ability and a deep belief in mathematical beauty and elegance. If an equation wasn’t beautiful, it probably wasn’t right. This led him to do “apparently unsound things that would annoy the mathematical purists”, like inventing the Dirac delta-function, which wasn’t mathematically respectable for decades, but he just knew it was right.

The Book Itself: Peeking Behind the Reticent Curtain

Farmelo, who is a senior research fellow at the Science Museum, London, and an associate professor of physics at Northeastern University, US, managed to write over 500 pages about this incredibly reserved man. He had access to Dirac’s personal papers, which is a true treasure for anyone trying to understand such a private individual.

The book is praised for being “incredibly detailed” about Dirac’s personal life and successfully bringing “so many of the characters in Dirac’s circle to life”. It covers not just Dirac, but also the “rise and golden age of quantum mechanics”, featuring giants like Einstein, Bohr, Heisenberg, Pauli, Born, Fermi, and Oppenheimer. It also paints a rich historical panorama, showing how science intertwined with World War II, the Cold War, and the Manhattan Project. It’s a “superb work” and an “excellent biography”.

Now, some folks had a little beef:

- Science Light: A recurring criticism is that while the personal life is super rich, the scientific details are “practically glossed over”. Some wished Farmelo had gone deeper into the physics, lamenting that “every time Farmelo recounted an amazing achievement of Dirac’s I felt as if I had been rushed through it”. However, to Farmelo’s credit, he aims to explain Dirac’s work in “general terms, without any scary equations”, making it accessible to non-physicists.

- The “A” Word (Autism): This is a hot topic in the reviews. Farmelo “postulates that he suffered from a high functioning form of autism”, and some reviewers found the “case that Dirac was solidly on the spectrum” to be “extremely compelling”. But others were “a little leery of this new trend to classify every genius as autistic lately”. Some felt the author’s psychological analysis was “superficial”, “uninformed”, or based on “unreliable sources”, even perpetuating “fallacious negative stereotypes about autism”. So, that’s a whole rabbit hole the book goes down, with mixed results for readers.

The Verdict: Is It Worth Your Precious Brain Calories?

Absolutely. “The Strangest Man” is “a fascinating glimpse into the birth of quantum mechanics, through the life of a man who was at once one of the pillars of the community and yet still an outsider”. It’s for anyone fascinated by “the lives of brilliant outsiders”, the history of science, or just how some brains work in ways that are, well, strange.

It perfectly encapsulates why Niels Bohr, another titan of physics, once said: “Dirac was the strangest man”. And after reading this, you’ll totally get it. It’s a journey into the mind of a guy who didn’t just walk the path of science; he built his own, guided by an almost mystical faith in mathematical beauty, and pulled new realities into existence from pure thought.

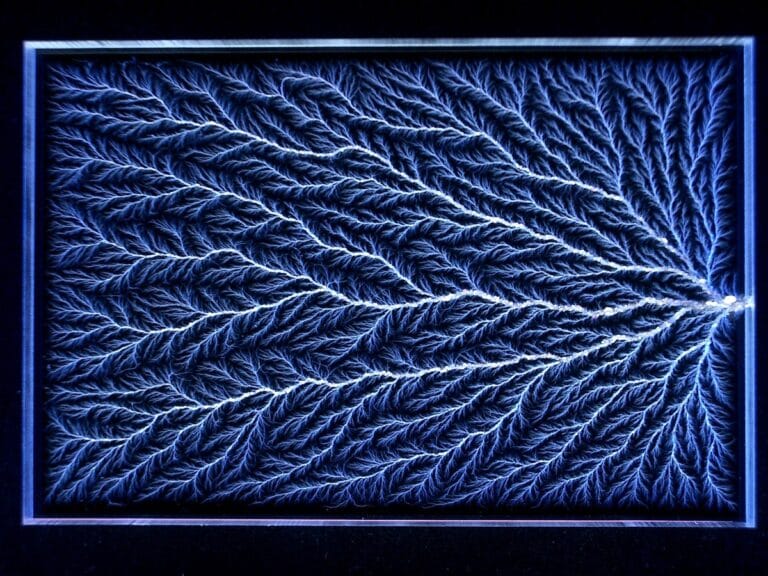

Alright, let’s take a deep dive, because what we have here is the story of a man whose relationship with the ordinary was, well, fractured. We’re talking about Benoit Mandelbrot, and his memoir, “The Fractalist“. This book promises to open a window into his life and the storm of ideas within his head. But, as with many complex systems, this window can sometimes be foggy, and other times reveal a breathtaking vista.

First off, the man’s life was nothing short of a wild journey. Born in Warsaw in 1924, Mandelbrot and his family moved to Paris in the 1930s, fleeing the growing threat. During World War II, he famously hid from the Nazis until liberation, studying mathematics in secret, almost like a scene out of a movie. Imagine being on the run for your life, yet secretly honing the mind of a future genius! He emerged from this turmoil to become France’s top math student. This early period of the book is particularly gripping and fascinating.

Mandelbrot himself famously stated, “Unimaginable privilege, I participated in a truly rare event: pure thought fleeing from reality was caught, tamed, and teamed with a reality that everyone recognized as familiar”. This encapsulates the essence of his unique perspective.

Mandelbrot doesn’t fit the typical mold of a “duly-recognized genius”. While many mathematicians produce their most significant work in their youth, our protagonist was the opposite. His groundbreaking work in finance came as he neared forty, and the discovery of the Mandelbrot Set itself came when he was fifty-five years old! He truly was a “good wine that ages well” kind of genius. This offers profound hope to anyone who feels they’ve “missed the boat” or are on “the road less traveled”. His story is an inspiration to those who forge their own path.

He identified deeply with George Bernard Shaw’s assertion: “The reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore, all progress depends on the unreasonable man.”. This philosophy clearly guided his scientific journey.

His uncle, Szolem, played a truly immense role in his life. Szolem seemed to be Mandelbrot’s compass, showing him that mathematics wasn’t just about calculations, but could also be poetry and art in its search for truth, beauty, and intuition. This family legacy likely fed his desire to conquer “roughness”. Think of mountain ranges, clouds, financial market fluctuations—those irregular, complex structures in nature. This obsession with mathematically describing the “rough edges” of the world pushed him to create fractal geometry. And in doing so, he made mind-expanding insights like: “Complicated shapes might be easily understood dynamically as processes, not just as objects”, and “Bottomless wonders spring from simple rules…repeated without end.”. This offers a deep perspective on the workings of the universe and even financial markets.

Now, let’s address the areas where the book, much like a fractal, repeats patterns that might become a little disjointed or even annoying.

- The Name-Dropping Extravaganza: There’s an undeniable “name-dropping epidemic”. Every few pages, you encounter a famous scientist, a genius, a professor: Oppenheimer, von Neumann, Lévi-Strauss, Chomsky, Piaget. While it’s impressive who he knew, some readers felt it was as if he was “trying to legitimize himself when he didn’t need it”. One wishes he had delved deeper into how these brilliant minds truly shaped his own thought processes, rather than just stating “we met, they were smart”. He was “not very good at writing about them”.

- Where’s the Math, Bapak Fractalist?: You’d expect the “father of fractals” to offer a deep dive into the mathematics, wouldn’t you? Yet, the book contains only one very simple formula. It’s almost as if it’s saying, “Let’s not get too technical, this is a memoir”. But when you’ve done something so revolutionary, one yearns to understand how those complex, infinitely beautiful shapes emerge from such a simple rule. Instead of describing the boring administrators at IBM, some readers wished for more profound discussions, such as on Kolmogorov-Chaitin complexity.

- The Veiled Personal Life: Mandelbrot dedicates very little space to his personal life, with his introduction to his wife, Aliette, covered in just two pages. His family life also receives scant attention. While he may have wished to protect their privacy, it leaves readers wondering “how his wife and family helped shape his person and thoughts”.

- The Writing Style – A Fractal Itself?: The book’s writing style can be somewhat disjointed, repetitive, and uneven. It feels as if Mandelbrot, who finished the memoir shortly before his death, didn’t have the chance to fully edit it. There’s also a recurring theme of self-congratulation and ego that some readers found off-putting.

So, what’s the takeaway? “The Fractalist” is fundamentally an adventure story about the life of a mathematical genius, presented as a memoir. If you’re expecting a deep, analytical dive into Mandelbrot’s scientific contributions, you’re better off heading straight for his other works, like “The Fractal Geometry of Nature“.

However, if you’re curious about the journey of a non-conformist mind, a man who challenged boundaries, and lived by the philosophy of the “unreasonable man”, then give this book a shot. You won’t regret it. Just be prepared for a few “hmm” or “I wish” moments along the way. Because this man is a rare example of a scientist who “reinvented himself surprisingly late in life”, and that, in itself, is utterly captivating. It’s recommended for “anyone interested in geometry, math, fractals or men of science. Or anyone interested in memoir”. It offers an “interesting insight into the life and work of Benoit Mandelbrot”.

Experience the brilliance of Albert Einstein’s groundbreaking theories in Relativity: The Special and the General Theory. First published in 1920, this timeless masterpiece continues to captivate readers with its unique blend of scientific insight and accessible language.

In celebration of the centennial of general relativity, the 100th anniversary edition of the book, translated by Robert W. Lawson and edited by Hanoch Gutfreund and Jürgen Renn, offers a fresh perspective with added historical context. Gain a deeper understanding as you explore Einstein’s path to his field equations and unlock the secrets of the universe.

Einstein’s descriptions of special relativity are both pleasurable and easy to read, making it an ideal resource for students. With gentle and intuitive derivations, the concepts of time dilation, length contraction, and the Lorentz transformations come to life. Even the more technical explanations in the appendix are easily understood by undergraduate physics students.

Delve into the world of general relativity and experience Einstein’s own words as he describes the intricacies of spacetime and curved space. Gain valuable insight into non-Euclidean geometry and develop a newfound intuition for the subject.

While the general relativity section may require some prior knowledge, it remains a captivating read for physicists and those with a keen interest in the field. Discover the gems hidden within the post-1917 editions, including Arthur Eddington’s measurement of the deflection of light by the Sun’s gravitational field and Einstein’s evolving understanding of the universe.

Embark on an intellectual journey with Relativity: The Special and the General Theory. Experience the enduring impact of Einstein’s theories and witness the survival of special and general relativity through rigorous scientific testing. With a compelling historical introduction by Gutfreund and Renn, this book is a must-read for physicists and curious minds alike. Uncover the mysteries of the universe and expand your knowledge today.