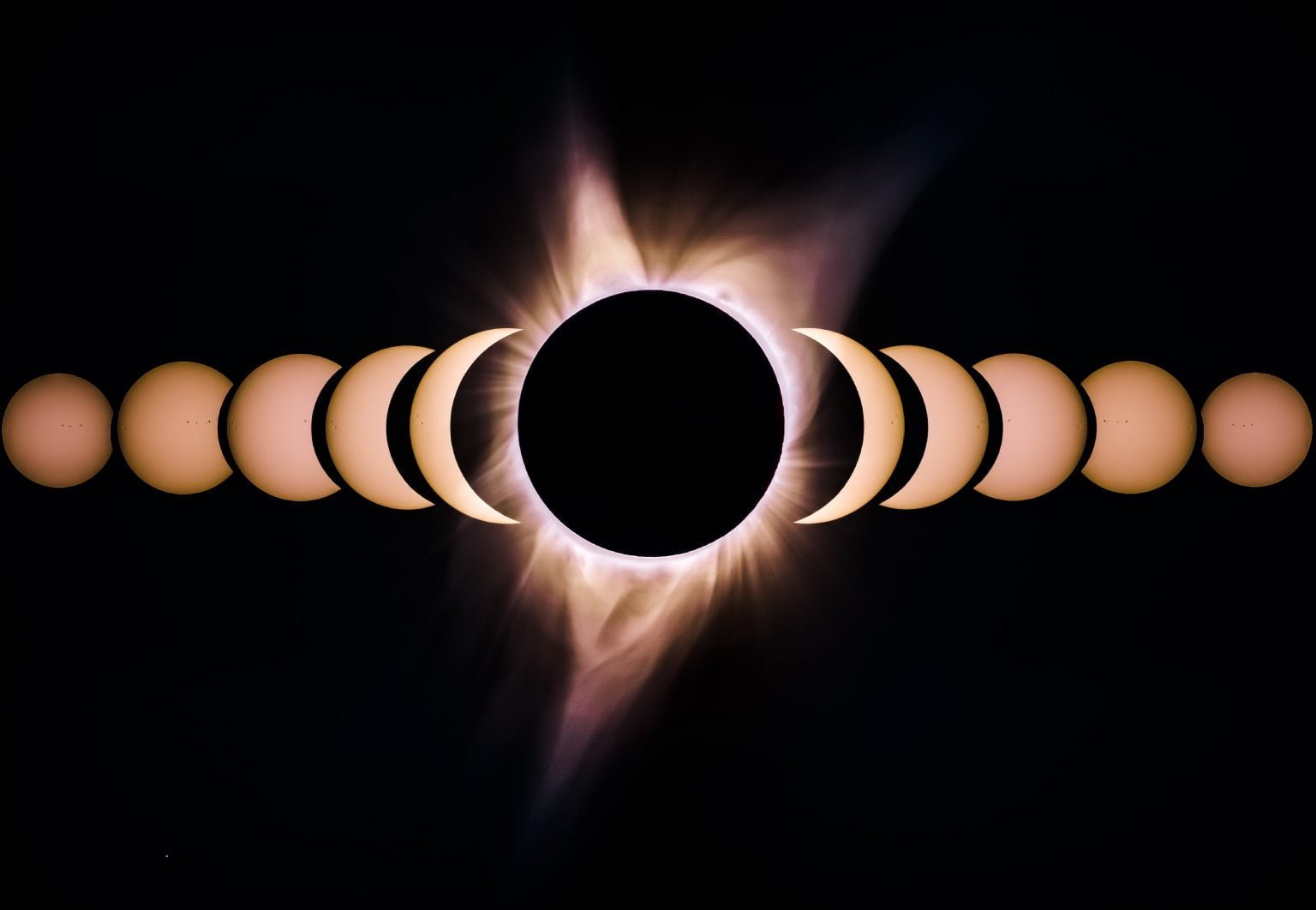

If and when physicists are able to pin down the metal content of the sun, that number could upend much of what we thought we knew about the evolution and life span of stars.

Like any star in its prime, the sun consists mainly of hydrogen atoms fusing two by two into helium, unleashing immense energy in the process. But it’s the sun’s tiny concentration of heavier elements, which astronomers call metals, that controls its fate. “Even a very small fraction of metals is sufficient to alter the behavior of a star completely,” explained Sunny Vagnozzi, a physicist at Stockholm University in Sweden who studies the “metallicity” of the sun. The more metallic a star, the more opaque it is (since metals absorb radiation), and how opaque it is in turn relates to its size, temperature, brightness, life span and other key properties. “Metallicity basically also tells you how the star will die,” Vagnozzi said.

But the sun’s metallicity, beyond revealing its own story, also serves as a kind of yardstick for calibrating measurements of the metallicity of all other stars, and thus the ages, temperatures and other properties of stars, galaxies and everything else. “If we change the solar yardstick, automatically it means that our understanding of the cosmos has to change,” said Martin Asplund, an astrophysicist at Australian National University. “So having an accurate knowledge of the solar chemical composition is extremely important.”

Yet, ever more precise measurements of the sun’s metallicity have raised more questions than they’ve answered. Astronomers’ inability to solve the mystery known variously as the solar metallicity, solar abundance, solar composition or solar modeling problem suggests there could be “something fundamentally wrong” with their understanding of the sun, and therefore of all stars, said Vagnozzi. “That would be huge.”

Twenty years ago, astronomers thought they had the sun sorted. Direct and indirect ways of inferring its metallicity both gauged the sun as approximately 1.8 percent metal — a happy convergence that led them to believe they understood not only the length of their solar yardstick but also how the sun works. However, throughout the 2000s, increasingly precise spectroscopic measurements of sunlight — a direct probe of the sun’s composition, since each element creates telltale absorption lines in the spectrum — indicated a far lower metallicity of just 1.3 percent. Meanwhile, helioseismology, the competing, indirect approach for inferring metallicity based on the way sound waves of different frequencies propagate through the sun’s interior, still said 1.8 percent.