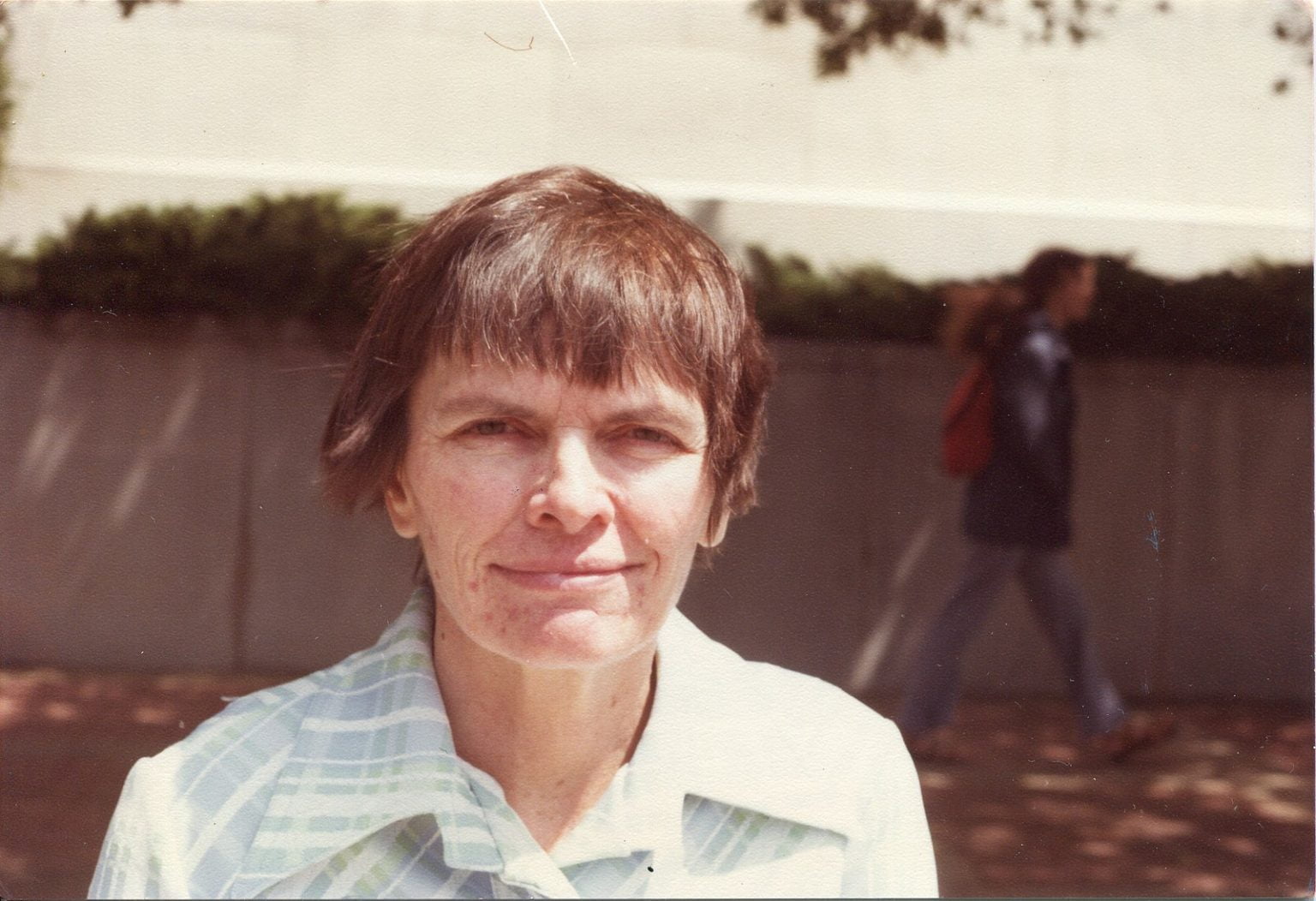

Every December 8 for years, Julia Robinson blew out the candles on her birthday cake and made the same wish: that someday she would know the answer to Hilbert’s 10th problem. Though she worked on the problem, she did not care about crossing the finish line herself. “I felt that I couldn’t bear to die without knowing the answer,” she told her sister.

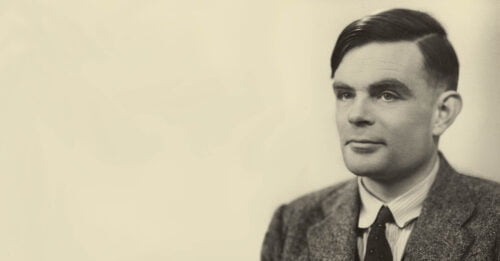

In early 1970, just a couple of months after her 50th birthday, Robinson’s wish came true. Soviet mathematician Yuri Matiyasevich announced that he had solved the problem, one of 23 challenges posed in 1900 by the influential German mathematician David Hilbert.

Matiyasevich was 22 years old, born around the time Robinson had started thinking about the 10th problem. Though the two had not yet met, she wrote to Matiyasevich shortly after learning of his solution, “I am especially pleased to think that when I first made the conjecture you were a baby and I just had to wait for you to grow up!”

The conjecture Robinson was referring to was one of her contributions to the solution to Hilbert’s 10th problem. Matiyasevich put the last piece into the puzzle, but Robinson and two other American mathematicians did crucial work that led him there. Despite the three weeks it took for their letters to reach each other, Robinson and Matiyasevich started working together through the mail in the fall of 1970. “The name of Julia Robinson cannot be separated from Hilbert’s 10th problem,” Matiyasevich wrote in an article about their collaboration.

Robinson was the first woman to be elected to the mathematics section of the National Academy of Sciences, the first woman to serve as president of the American Mathematical Society and a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship. She achieved all of this despite not being granted an official faculty position until about a decade before her death in 1985.

Robinson never thought of herself as a brilliant person. In reflecting on her life, she focused instead on the patience that served her so well as a mathematician, which she attributed in part to a period of intense isolation as a child. At age 9, while living with her family in San Diego, she contracted scarlet fever, followed by rheumatic fever.

Penicillin had just been discovered and was not yet available as a treatment. Instead, she lived at the home of a nurse for a year, missing two years of school.

Even after she rejoined her family, attended college and married, complications from rheumatic fever led to lifelong health problems, including the inability to have children. After a much-wanted pregnancy ended in miscarriage, doctors told her another pregnancy could kill her. She had a heart operation when she was around 40 years old that improved her health, but she was never able to have the family she deeply desired.