Everyone knows Richard Feynman as the mischievous physicist with a bongo under one arm and a piece of chalk in the other—but far fewer know him through something just as revealing: the Drawings of Richard Feynman. Long before the public ever saw his sketches, he was quietly filling notebooks with dancers, friends, scientists, strangers, and quick flashes of daily life.

These drawings open a different door into his mind, showing how the same curiosity that built quantum physics also pushed him to understand light, shadow, movement, and emotion through pencil and paper. What you discover, as you move through these sketchbooks, is that Feynman wasn’t just explaining the universe—he was observing it with the same intensity whether he was drawing atoms or drawing people.

Feynman didn’t pick up drawing seriously until 1962, at the age of 44. The spark came from his close friend, artist Jirayr “Jerry” Zorthian. Imagine their endless debate: Which is superior—art or science? Eventually, after enough banter and back-and-forth, they struck a deal: every Sunday they would take turns teaching each other—one week art, the next week science. The timing is striking. Feynman had just invented the visual language of Feynman diagrams, reshaping physics by literally turning equations into pictures. After giving the scientific world a new way to think visually about particles, he turned around and taught himself to see people with the same curiosity.

Feynman explained his motivation in words only he could deliver: “I wanted to convey an emotion I have about the beauty of the world.” The feeling he describes is almost religious—the awe of recognizing that wildly different phenomena obey the same underlying physical laws. He wanted his drawings to carry this “scientific awe,” to remind someone, even if just for a moment, of the deep, hidden harmony of the universe. Reading that, you immediately understand why drawing became meaningful to him. It wasn’t an escape. It was simply another way of understanding.

And when you look at the drawings, this becomes obvious. The dancer at Gianonni’s Bar. The soft, resting form of “Sleeping.” The scribbled equations sitting beside a sketch of a face. Hans Bethe’s wrinkles. A casual portrait of his daughter Michelle. Even the small, charming page where little Carl Feynman adds the last line with his two-year-old hand. These aren’t the works of someone trying to be an artist. They’re the works of someone trying to see.

When friends suggested selling the drawings, Feynman immediately hesitated. He didn’t want anyone valuing them simply because of his fame. So he invented a pseudonym: Ofey. The origin story is peak Feynman—his friend suggested the French phrase “Au Fait,” he misspelled it, later learned it was slang for “white man,” shrugged, and said, “Well, I am white.” And that was that.

One of the most striking parts of the notebook collection is Feynman’s reflection on teaching. He noticed that art teachers avoid giving direct instructions—if someone draws with unusually heavy lines, a teacher won’t correct them because somewhere out there an artist uses heavy lines brilliantly. “The drawing teacher has to communicate by osmosis,” Feynman writes. Physics, on the other hand, is the opposite. It’s technique after technique, method after method. His observation reveals something profound: science has rules, but learning—real learning—needs freedom. Art gave him a taste of that.

The sketchbooks shift constantly between quick one-minute drawings and careful, patient studies. The 1968 dancer has the energy of a moment caught mid-motion. The 1985 “Equations and Sketches” page weaves formulas and face studies as if they belong to the same universe. And in Feynman’s life, they did. His physics wasn’t sterile abstraction—it was a way of seeing. The drawings merely reveal the other half of that vision.

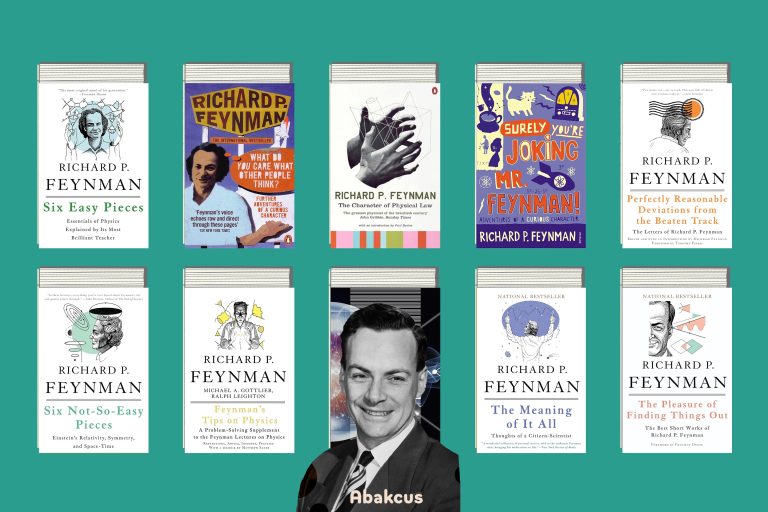

And this is where, almost automatically, your mind drifts to his books. Because Feynman wrote the way he drew: with curiosity, humor, and an almost childlike enthusiasm for how things work. That’s why I once put together a small list—gentle, unpretentious, and full of that Feynman spirit—called The Art of Understanding Physics with Richard Feynman’s Books. Those books feel like an extension of the sketchbooks: one set captures the world in lines and bodies, the other captures it in ideas and stories. Flip through the drawings and then open one of the books; you feel like you’re holding two different notebooks from the same restless mind. He draws atoms with chalk, people with charcoal, and the universe with words.

And there is another beautiful parallel worth slipping in here—the way Feynman learned. Because he didn’t just sketch people; he taught himself mathematics with the exact same curiosity. One of my favorite examples is the notebook he kept while teaching himself calculus from scratch. I wrote about it separately in a piece titled Richard Feynman’s Notebook: How He Taught Himself Calculus, because that notebook is essentially a window into his mind. You see him interrogating every step: “Do I really understand this? If not, why?” Just as his sketchbooks show him breaking down the curves and shadows of a human body, his calculus notebook shows him breaking down the logic behind limits, derivatives, and integrals. Whether he was learning art or math, his method was identical: rebuild everything from the ground up, in his own language.

Most of these drawings were eventually gathered by Michelle Feynman in The Art of Richard P. Feynman: Images by a Curious Character. The book is out of print now, a collector’s item. But the introductory essay “But Is It Art?”—preserved in the PDF—remains one of the clearest windows into why Feynman drew at all. If you’ve only met him through his lectures, his Nobel acceptance, his wild stories, or Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman, these sketches unlock a quieter side of him. A man who could sit still. A man who observed carefully. A man who, despite understanding the universe at its deepest level, still looked at the world with a kind of innocent surprise.

The last page of the PDF shows his very first drawing, from 1962. It’s not particularly impressive—at least not artistically. But it is emotionally meaningful. It shows that even a genius begins clumsily when starting something new. It proves that mastery in one domain doesn’t translate magically into another. And more importantly, it reveals Feynman’s greatest secret: he never stopped being a student. Drawing didn’t make him less of a scientist. If anything, it made him a better one.

Feynman’s sketchbooks remind us that understanding the world is never just an intellectual task. Sometimes the path to comprehension runs through observation, patience, curiosity, or even the wobbling charcoal line of a one-minute drawing. Sometimes the universe becomes clearer when we don’t calculate it—but when we try to draw it.