Math in movies has always had a curious kind of magic. On paper, numbers can look lifeless—just chalk dust floating across a blackboard, just another page of dry formulas tucked away in a textbook. But cinema has a way of changing everything. When film directors decide to put mathematics on screen, it transforms into something deeper: drama, philosophy, even raw human emotion.

We’ve seen it in countless forms. Sometimes math in movies shows up as a lone genius scribbling equations late at night, caught between brilliance and madness. Sometimes it appears as a breathtaking visual, where abstract formulas are brought to life as spirals, fractals, or dazzling sequences of symmetry. And sometimes it’s hidden in the smallest moments—a quick joke in a classroom, a gambler’s calculation at a poker table, or a whispered line of probability that changes the way we see a character.

What makes these scenes special is that math is never just math. In movies, numbers often become metaphors. They can represent love, order, chaos, infinity, or the very fabric of the universe itself. A formula on a blackboard can symbolize obsession, a counting scene can reflect survival, and a probability equation can turn into a meditation on fate.

This collection brings together some of the most beautiful, fascinating, and unforgettable math in movies moments ever put on screen. From quiet dramas to loud blockbusters, from the elegance of Euclid’s logic to the messy probability of Russian roulette, these films show that mathematics can be more than numbers—it can be a character in the story.

So whether it’s equations that change the course of history, paradoxes that bend time, or simple jokes about multiplication that still make us laugh, this guide celebrates the many ways math in movies has shaped how we imagine knowledge, beauty, and truth. At its best, cinema doesn’t just use mathematics as a backdrop—it gives it a soul.

Good Will Hunting: Blackboard Problems in Graph Theory and Linear Algebra

Gus Van Sant’s Good Will Hunting (1997) has become one of the most famous examples of mathematics on film. Matt Damon plays Will Hunting, a janitor at MIT with a hidden genius for mathematics. In one of the film’s most memorable sequences, Will pauses while cleaning a hallway, notices a problem written on a blackboard, and solves it with ease.

The problems he tackles are drawn from graph theory and linear algebra—fields that deal with structures, connections, and transformations. In the story, they’re posed as formidable challenges for graduate students, but in reality, none of them are unsolved or particularly exotic; they’re advanced, yes, but standard material in upper-level courses.

The point isn’t the difficulty of the problems, but what they reveal: Will’s natural brilliance, and his world colliding with academia in an unexpected way. That’s why Good Will Hunting holds such a prominent place in the canon of math in movies. It captures the romance of mathematics—not as an impossible riddle, but as a language that can transform an ordinary janitor into something extraordinary.

Interstellar: Mathematics Across Space and Time

Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014) is one of the most ambitious attempts to bring real science into blockbuster cinema, and mathematics lies at its core. The original screenplay was developed with the guidance of Kip Thorne, a Caltech physicist who spent decades studying the mathematics of wormholes and relativity. His work didn’t just inspire the story—it shaped the film’s visuals and grounded its wildest ideas in real equations.

Mathematics here isn’t background dressing. It appears in the form of gravitational equations scrawled across blackboards, the calculations of time dilation near a black hole, and the effort to solve the equation that could allow humanity to escape Earth. Even the depiction of the black hole Gargantua was generated from Thorne’s equations, producing imagery so accurate it later led to a scientific paper.

This is why Interstellar is one of the most celebrated examples of math in movies. It doesn’t just use formulas as props—it shows how mathematics can be the bridge between imagination and reality, between storytelling and the cosmos itself.

Moneyball: Cutting Through Bias with Statistics

Bennett Miller’s Moneyball (2011) is one of the clearest examples of mathematics transforming not just a story, but an entire sport. Based on the true story of Billy Beane and the Oakland A’s, the film shows how equations and statistics, championed by the character Peter Brand (a stand-in for Paul DePodesta), reshaped the way baseball players were valued.

Instead of relying on gut instinct or superficial judgments—age, appearance, personality—Brand applies sabermetrics: mathematical models that measure on-base percentage, slugging, and other overlooked factors. The math cuts straight through human bias, revealing hidden value in players dismissed by traditional scouts.

What makes Moneyball a landmark in the tradition of math in movies is that the numbers don’t just sit on a blackboard—they change lives, teams, and the economics of an entire sport. The equations are simple, but their impact is enormous: proof that sometimes math isn’t just about solving problems, it’s about rewriting the rules of the game.

Fight Club: The Insurance Equation

David Fincher’s Fight Club (1999) is remembered for its anarchic philosophy, gritty visuals, and the unforgettable pairing of Brad Pitt and Edward Norton—two performances that, as fans often joke, form their own “equivalence class.”

Amid the chaos, there’s a small but telling math moment: an insurance equation. Norton’s character, working as a recall coordinator, explains the cold logic behind corporate decisions on defective products. The formula weighs the cost of settlements against the cost of a recall: If (A×B×C)<X, no recall.\text{If } (A \times B \times C) < X, \text{ no recall}.If (A×B×C)<X, no recall.

Here, AAA is the number of vehicles, BBB the probability of failure, CCC the average cost of a lawsuit, and XXX the cost of a recall. It’s brutal arithmetic—life and death reduced to a calculation of profitability.

This moment is one reason Fight Club holds a place in the catalogue of math in movies. It’s not about abstract equations, but about how mathematics can be stripped of humanity, exposing a system where numbers dictate morality.

Dead Poets Society: The Prichard Scale of Poetry

Peter Weir’s Dead Poets Society (1989) is remembered for Robin Williams’ unforgettable performance and its call to “seize the day.” But before the soaring speeches and rebellious verse, the film begins with a curious bit of mathematics applied to art: the Prichard Scale of Understanding Poetry.

In a textbook, poetry is reduced to a formula: Greatness=Perfection×Importance.\text{Greatness} = \text{Perfection} \times \text{Importance}.Greatness=Perfection×Importance.

On a “P–I plane,” students are told they can measure a poem’s value by plotting these variables like points in geometry. It’s a deliberately absurd taxonomy, stripping poetry of mystery and squeezing it into an equation.

Of course, the point is not the math itself but its rejection. John Keating (Williams) has his students rip the pages from the book, showing that poetry—and by extension life—cannot be quantified so neatly.

This brief formula is what earns Dead Poets Society a memorable spot in the history of math in movies. It illustrates both the seduction and the futility of trying to measure beauty with numbers.

Rain Man: Counting Toothpicks

Barry Levinson’s Rain Man (1988) is filled with unforgettable moments, but one scene in particular has become iconic for showing the extraordinary abilities of Dustin Hoffman’s character, Raymond Babbitt.

When a waitress drops a box of toothpicks on the diner floor, Raymond glances at them and immediately announces: “246 toothpicks.” His brother Charlie (Tom Cruise) is skeptical, but the waitress quickly checks the box—there were 250 inside, and four remain. Raymond’s instant calculation is correct.

The scene dramatizes savant syndrome with a mix of awe and poignancy. Raymond’s gift with numbers is astonishing, but it also isolates him. The math here isn’t presented as abstract theory or classroom exercise—it’s intuitive, immediate, almost visceral.

That’s why Rain Man is often cited among examples of math in movies. The toothpick scene captures both the beauty and the complexity of extraordinary mathematical ability, reminding us that numbers can be as human as they are precise.

A Serious Man: The Uncertainty Principle on Screen

The Coen brothers’ A Serious Man (2009) is essentially one long meditation on the Uncertainty Principle. From the opening nod to Schrödinger’s cat, to songs about blurred boundaries, to the fuzzy chaos of TV reception, the film leans fully into the idea that not everything can—or should—be pinned down with certainty. Even the relationships in the story seem to “quantum tunnel” from one state to another, mirroring the physics at its core.

It’s one of the best Coen brothers movies precisely because it refuses to give neat answers. Instead, it celebrates ambiguity, mystery, and the limits of control—both scientific and personal.

And then there’s the sly detail for math-minded viewers: a blackboard computation with a deliberate error. Whether it was a slip or, more likely, a purposeful choice, it works on a meta level, echoing the film’s theme that certainty is always just out of reach.

Moments like this show why math in movies can be more than background decoration. Sometimes the mathematics isn’t just in the equations—it’s the philosophy the entire story is built on.

The Physician: Knowledge, Balance, and the Music of the Spheres

Philip Stölzl’s The Physician (2013), adapted from Noah Gordon’s novel, takes us from 11th-century England to Isfahan, then one of the great intellectual centers of the Islamic Golden Age. It tells the story of Rob Cole, who begins life as a miner’s child, then follows a wandering barber-surgeon before finally studying with the great polymath Avicenna (Ibn Sina, played by Ben Kingsley).

The film vividly portrays an age when science, religion, and philosophy were deeply intertwined. In Islam, as in medieval Europe, religion was both a reason to question the world and a reason to restrain inquiry. Astronomy mattered not just for navigation but also for religious ritual, and mathematics carried both sacred and practical significance—for trade, architecture, and medicine. Even the word algebra comes from the Arabic al-jabr, meaning “restoring balance” or “mending broken bones,” a perfect metaphor within the film’s medical setting.

Mathematics is never shown directly on a blackboard, but it lingers in the atmosphere: in discussions of resonance, in the idea of the “music of the spheres,” and in repeated mentions of Aristotle’s philosophy. These subtle touches remind us how numbers and harmony were once inseparable from the search for truth.

That’s why The Physician earns a place among examples of math in movies. Here, math isn’t a puzzle to be solved—it’s a cultural force, a sacred language, and a bridge between science, faith, and healing.

Lincoln: Euclid’s Common Notion

Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln (2012) is filled with powerful speeches, but one of the most striking moments rests on a piece of mathematics. Abraham Lincoln, portrayed by Daniel Day-Lewis, invokes Euclid’s Common Notion:

“Things which are equal to the same thing are equal to each other.”

It’s a line from The Elements, written more than two millennia earlier, yet it carries immense moral weight in the film. Lincoln uses Euclid not as geometry but as philosophy—an appeal to logic and fairness that transcends politics.

This moment shows how mathematics in movies can act as rhetoric. By grounding his argument in Euclid’s timeless clarity, Lincoln frames equality not as opinion, but as an undeniable truth. And that’s why this brief reference earns Lincoln a place in the catalogue of math in movies: a reminder that sometimes the purest logic is also the most human.

Travelling Salesman: P = NP and Scientific Ethics

Travelling Salesman (2012) is one of the rare films that takes mathematics seriously—not just as window dressing, but as the beating heart of the story. At its center is the famous P = NP problem, one of the great unsolved questions in computer science, first formulated by Stephen Cook and Leonid Levin. The script even tips its hat to Michael Garey and David S. Johnson, whose seminal work Computers and Intractability shaped the field.

The film plays a lot like a stage drama, echoing Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s Die Physiker. In both, scientists grapple with the ethical weight of their discoveries while others—often silent observers—listen in. Dürrenmatt had Mathilde von Zahnd, the psychiatrist who eavesdrops; here we have a shadowy bodyguard hovering over the conversation. The atmosphere carries a Cold War edge, much like Dürrenmatt’s 1962 play where NATO and the Warsaw Pact loom in the background.

What makes Travelling Salesman so compelling is that the mathematics isn’t just there for show. The problem of P vs. NP embodies the tension between intellectual curiosity and political power, between discovery and control. As a piece of cinema, it reminds us why math in movies can matter so much: equations can change the world—but whether for better or worse depends on who holds the solutions.

Just Before I Go: A Flashback with Math

Courteney Cox’s Just Before I Go (2014) is a darker but ultimately uplifting comedy that features one of Seann William Scott’s strongest performances—far from his over-the-top American Pie persona, closer in spirit to the quiet transformation Steve Carell achieved in Little Miss Sunshine.

Amid its story of reckoning and redemption, the film slips in two short math scenes, both framed as flashbacks. The classroom setup is almost comically staged: kids at their desks with mismatched books (one even has a Greek history volume), while a green chalkboard shows homework problems 1–12 in the blandest possible form. It’s not about the math itself—those problems couldn’t be more unimaginative—but about the memory, the texture of a classroom frozen in time.

It’s a small detail, but one that earns Just Before I Go a spot in the quirky tradition of math in movies. The equations might be dull, but the scene adds authenticity to the flashback and another layer to the film’s bittersweet exploration of life, regret, and humor.

The Red Violin: Eigenmodes and Mystery

François Girard’s The Red Violin (1998) is remarkable for many reasons: it’s a beautifully woven story, filled with stunning violin solos, and built like a detective tale. Piece by piece, the film uncovers the history of a mysterious violin, moving across centuries and continents, leaving behind questions of fate, ownership, and desire.

Who will ultimately claim it? The monks in the Austrian Alps who safeguarded it, the young Gypsy violinist, the Vatican foundation’s representative, the virtuoso Mr. Ruselsky, the Chinese investor, Xiang Pei who played it as a forbidden child in Shanghai, or the investigator (Samuel L. Jackson) who traces its journey for the auction house?

Amid this intricate tale, mathematics finds a subtle place through the idea of eigenmodes—the natural vibration patterns that give the violin its voice. Every instrument resonates differently, and in the film, the mystery of the red violin is tied not only to its history but also to the physics and mathematics of its sound.

That’s why The Red Violin deserves its place in the collection of math in movies. Here, mathematics isn’t on a blackboard but hidden inside music itself—the unseen structure of resonance that makes the instrument’s story, and its sound, unforgettable.

Calculus of Love: Obsession with Goldbach’s Conjecture

Calculus of Love is a film that blends romance with mathematics, showing how obsession with an unsolved problem can seep into every corner of life. At its core is the Goldbach Conjecture, the 18th-century hypothesis that every even integer greater than two is the sum of two prime numbers.

The story follows this mathematical fixation not as a dry puzzle, but as a metaphor for desire, longing, and the search for completeness. Just as the conjecture remains unproven yet deeply compelling, the film’s characters circle around mysteries of their own—emotional, intellectual, and romantic.

Without giving away the ending, the film concludes on a surprising note, reminding us how unpredictable both love and mathematics can be. It’s an unusual but striking example of math in movies: proof that equations can drive a story as powerfully as any human passion.

Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3: Rocket Does the Math

James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 (2023) is full of spectacle, heart, and chaos—but tucked inside the action is a small moment of mathematics. Rocket, the team’s quick-thinking raccoon, is shown scribbling through math computations on a tablet.

It’s brief, almost easy to miss, but it fits Rocket’s character perfectly. He’s always been the tinkerer and strategist, the one who can improvise a solution when everyone else is panicking. The math here reinforces that side of him: calculation as survival, equations as tools every bit as important as blasters or spaceships.

The scene doesn’t dive into detail, but it’s enough to earn Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 a playful place in the catalogue of math in movies. Sometimes even in the Marvel universe, saving the day starts with running the numbers.

Safe: A Girl with Numbers

Boaz Yakin’s Safe (2012) delivers Jason Statham’s signature brand of action, but at its core is a story driven by mathematics. The plot centers on a young girl with an extraordinary memory and remarkable math talent. The numbers she carries in her head are so valuable that she becomes the target of ruthless pursuit by rival mafias and corrupt officials.

Here, math isn’t about solving classroom problems—it’s about power. A single sequence of digits can save lives or destroy them. In the chaos of the chase, numbers turn into security codes, hidden accounts, and life-or-death stakes.

That’s what makes Safe a unique entry in the tradition of math in movies. The math itself may be brief on screen, but it’s the hidden force that drives the story forward: in a world of violence and betrayal, everything is bound together by the quiet inevitability of numbers.

Miss Fisher and the Crypt of Tears: A Perfect Triangle

In the stylish adventure Miss Fisher and the Crypt of Tears (2020), mathematics slips in for just a moment. Amid the mystery and archaeology, a perfect triangle appears—geometric precision hidden in the dust of ancient secrets.

It’s a brief detail, but it fits the film’s playful mix of glamour and puzzle-solving. The triangle isn’t explained at length; instead, it serves as a visual reminder that order and symmetry underlie even the wildest adventures.

Moments like this are what make the hunt for math in movies so enjoyable. Sometimes it’s a blackboard filled with equations, other times it’s simply the quiet elegance of a triangle, perfectly formed, waiting to be noticed.

Annihilation: A Fractal Ending

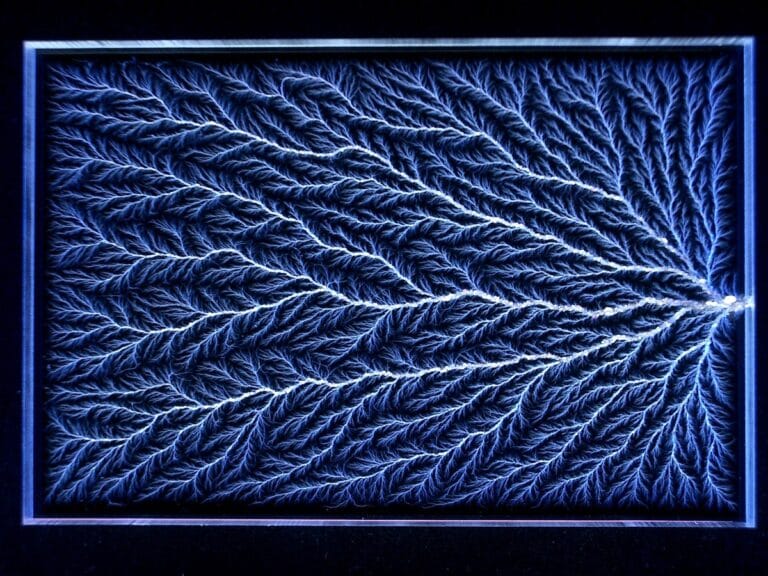

Alex Garland’s Annihilation (2018) closes with one of the most hauntingly beautiful end sequences in recent science fiction. The film itself is heavy, unsettling, and—depending on your taste—maybe a little too bleak. (I’m with you: horror without at least some kind of hopeful ending can be tough to love.)

The finale doesn’t contain any explicit mathematics, but it feels deeply math-inspired. The imagery has the texture of fractals, almost like something generated by an iterated function system. Shapes unfold, duplicate, and twist in patterns that feel both alien and familiar, echoing the recursive beauty of mathematics.

For anyone who’s experimented with fractal software like Apophysis, the resemblance is uncanny. The sequence becomes more than just a special-effects showcase—it’s a meditation on transformation and self-similarity, ideas that lie at the heart of math as much as they do at the core of this story.

Even without formulas or equations, Annihilation earns its place among examples of math in movies—not through calculation, but through visual poetry rooted in mathematics.

Suicide Squad: Hypotenuse with Deadshot

Not many people go into Suicide Squad (2016) expecting trigonometry, but there it is. In one scene, Will Smith’s character “Deadshot” sits down with his daughter and casually works through a problem involving the hypotenuse. It’s a quick moment, but one of those little surprises that make you smile—math sneaking into a comic book blockbuster.

The film itself divided critics but pulled in audiences, becoming a box office hit. And yes, it has its flaws—some slow pacing here and there—but it also has a cast of likable, often funny actors who keep the chaos entertaining. For me, the trigonometry scene is just a bonus. A movie that slips in math automatically earns extra points, but Suicide Squad also works as a pure diversion: action, humor, and just enough downtime to let you write an exam on the side while watching.

This is exactly why looking for math in movies is so much fun—you never know where it’ll turn up. Sometimes in dramas, sometimes in classics, and sometimes in the middle of a comic-book frenzy with supervillains and explosions.

Ocean’s 8: 3D Printing a Heist

Gary Ross’s Ocean’s 8 (2018) carries on the franchise’s tradition of elaborate, improbable heists—but this time with a twist of modern tech. At the center is a spectacular necklace, recreated through 3D scanning and printing.

On screen, it looks slick and seamless: a quick scan from one side, a near-instant print, and voilà—a perfect replica, complete with moving parts. In reality, it’s far trickier. Scanning only the front of an object leaves gaps, complex jewelry pieces are notoriously difficult to reproduce, and even the $6,500 MakerBot Replicator Z18 shown in the movie produces plenty of support material that must be painstakingly cleaned away. The film even depicts a “zirconium” print of Michelangelo’s David—something no current printer, not even professional services with machines a hundred times more expensive, could pull off so effortlessly.

Still, the fantasy is fun. Anyone who’s wrestled with scans or tried to print even simple objects knows how much work hides behind the glossy montage. But that’s the charm of the Ocean’s series: the scams are ludicrous, the tech is exaggerated, yet it all adds to the spectacle. And in this case, the cameo of 3D printing makes Ocean’s 8 a curious entry in the broader story of math and technology in movies—part science, part illusion, all heist.

Agora: Hypatia and the Apollonian Cones

Alejandro Amenábar’s Agora (2009) is a historical drama and philosophical portrait set in 4th-century Alexandria. Rachel Weisz plays Hypatia, not only a philosopher and astronomer but also a scholar deeply devoted to the beauty of mathematics.

One of the film’s most striking scenes shows her reflecting on Apollonian cones with her students. Mathematics here isn’t presented as dry calculation but as a pathway to understanding the hidden order of the universe. Through the geometry of cones, questions of celestial motion and natural law come alive.

It’s a brief but profound mathematical moment, connecting Hypatia’s personal intellectual journey with humanity’s larger scientific curiosity. That’s why Agora holds a memorable place in the world of math in movies: the cones are not just shapes, but gateways to the mysteries of the cosmos.

Agora: Hypatia and Relative Motion

In Agora (2009), Rachel Weisz’s Hypatia is portrayed not just as a philosopher but as a true scientist, constantly questioning and testing ideas. One of the most memorable scenes shows her experimenting with relative motion.

Instead of abstract speculation, she takes objects in her hands and demonstrates how movement looks different depending on the observer’s perspective. It’s a simple experiment, but striking for its time—an ancient mind grappling with concepts that anticipate later breakthroughs in physics.

The scene captures why Agora belongs among examples of math in movies. Here, mathematics isn’t presented as formula or proof but as lived inquiry: a scientist using observation, intuition, and geometry to peel back the layers of the universe.

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: The Number 42

In Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy universe, mathematics takes the stage with a single number: 42. When the cosmic supercomputer Deep Thought is asked, “What is the meaning of life, the universe, and everything?” that’s the answer it gives.

Of course, 42 explains nothing—and that’s the joke. Adams brilliantly pits the certainty of mathematics against humanity’s endless search for meaning. Math delivers absolute answers, but if you don’t ask the right question, the answers are useless.

The film adaptation carries this scene with the same effect: in the middle of a grand science-fiction narrative, the solution to the greatest philosophical question turns out to be an ordinary number. That’s what makes it one of the most iconic examples of math in movies. Here, mathematics isn’t just a tool—it’s the punchline.

The Time Machine: Equations of Time

In The Time Machine (2002), adapted from H.G. Wells’ classic novel, mathematics makes a subtle appearance in the form of blackboard equations. As the protagonist wrestles with the possibility of building a machine to travel through time, we see fragments of calculations sketched out—symbols and formulas serving as the visual language of impossible ideas.

The details of the math aren’t explained (and, truth be told, probably wouldn’t hold up to scrutiny), but the blackboard work grounds the fantasy in a framework of logic. It suggests that time travel isn’t just magic, but something that can at least be imagined through equations.

It’s a brief but memorable touch—an example of math in movies being used as atmosphere. Even when the formulas don’t unlock the mystery, they lend weight to the dream that with enough chalk, thought, and imagination, time itself might bend.

Intacto: Luck by the Numbers

Juan Carlos Fresnadillo’s Intacto (2001) is a thriller built entirely on the idea of luck—who has it, how it can be transferred, and how it can run out. The film dresses its surreal story with flashes of probability and mathematics, making chance itself feel like a character.

Early on, characters talk in numbers: the odds of drawing an ace from a shuffled 52-card deck, the one-in-a-million chance of a plane crash, and the razor-thin probability of being the sole survivor among 237 passengers—a one in 237 million event. These figures aren’t just trivia; they become a way of measuring fate, giving the film a mathematical undertone.

Later, the tension spikes with a brutal Russian Roulette variant, in which five of six chambers hold bullets. Here the math is obvious, but the point isn’t calculation—it’s dread. The probabilities become a narrative tool, showing just how fragile survival really is.

That’s why Intacto stands out in the catalogue of math in movies. It’s not about equations or formulas, but about how numbers can frame chance, making luck feel like both science and superstition at once.

The 13th Warrior: Counting to 13

John McTiernan’s The 13th Warrior (1999), starring Antonio Banderas and Omar Sharif, is one of those films that has aged into cult status. It’s not a deep philosophical epic—it doesn’t need to be. Instead, it plays as a kind of caricature of heroism: straightforward, almost comic in tone, but filled with action, charm, and likable characters. Good and evil are clearly divided, and the story is driven by cultures coming together to face a common threat.

One of the most memorable—and surprisingly humorous—moments is the counting scene. Amid tents, warriors, and tension, numbers are spoken aloud in translation: from the Norsemen’s dialect into Latin, and then into English. What emerges is perhaps the most epic “count to 13” ever put on film, playful yet dramatic, and full of cultural layers.

Omar Sharif brings real gravitas to the film, even though it would become his last major role before retirement. And while the story is simple, the way it handles language, humor, and mathematics in this scene gives The 13th Warrior a quiet place in the landscape of math in movies. Counting, after all, is where mathematics begins—and here it’s wrapped in legend, language, and laughter.

The Hangover: Allen’s Math at the Blackjack Table

Todd Phillips’ The Hangover (2009) is pure comedy chaos, but one of its most famous scenes sneaks in a surprising amount of mathematics. As Allen (Zach Galifianakis) heads into a Vegas casino to count cards, the film gives us a visual montage of what’s happening inside his head: equations flashing across the screen, from simple arithmetic to trigonometric identities, probability calculations, and even Fourier series.

It’s played for laughs, of course—the socially awkward Allen suddenly transformed into a mathematical savant—but the formulas on screen are real. Fans have paused the scene countless times to identify them, spotting everything from basic binomial probabilities to advanced analysis.

This is why the sequence has become one of the most iconic examples of math in movies. It’s not just parody—it’s a playful nod to the way mathematics has always been associated with hidden knowledge, secret systems, and the possibility of beating the odds. In Vegas, math might be the ultimate superpower—at least until the hangover hits.

Better Off Dead: Nonsense in Math Class

Savage Steve Holland’s Better Off Dead (1985) is a black comedy that pushes absurdity so far it circles back into being funny. The film is early John Cusack—he plays Lane Meyer, a role he would later admit disappointment in, though his career would go on to much stronger performances.

One of the most memorable sequences is set in a math classroom. Vincent Schiavelli, who many will recognize as the sinister doctor in Tomorrow Never Dies, plays the eccentric teacher. He launches into an absurd, nonsensical problem:

“The three cardinal trapezoidal formations hereto made orientable in our diagram, creating our geometric configurations which have no properties, but with location.”

The “lesson” drags on until the students are visibly distraught. And then comes the punchline: tomorrow there’s more math, and they’ll need to memorize pages 39 through 110. Instead of despairing, the entire class cheers—everyone except Lane, who mutters that he’d be “better off dead.”

The scene is a perfect time capsule of 1980s comedy: over-the-top, ridiculous, and weirdly endearing. For fans of math in movies, it’s also a reminder that sometimes equations don’t matter at all—the comedy is in the sheer nonsense of the performance.

Palm Springs: Quantum Mechanics in a Time Loop

Like Groundhog Day, Max Barbakow’s Palm Springs (2020) traps its characters in a never-ending time loop. It’s a sharp comedy with strong performances, but it also adds a surprising twist: a dose of quantum mechanics.

Sarah, one of the loop’s unwilling participants, turns to EdX courses to try and break free. Among her lessons is quantum mechanics, which she uses to piece together a plan—entering the wormhole with an explosive belt to escape the cycle. Whether or not the physics holds up (spoiler: it doesn’t), the idea is just plausible enough to make the story more playful.

Like its predecessor Groundhog Day, the logic of the loop doesn’t fully withstand scrutiny, but that’s not the point. This is entertainment, and the science references give it a clever edge. It’s another fun example of how math in movies and physics in pop culture often serve less as literal science lessons and more as storytelling spice.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind: Fractions and Mysterious Coordinates

Steven Spielberg’s 1977 Oscar-winning film Close Encounters of the Third Kind is remembered as one of cinema’s most iconic depictions of first contact with aliens. But hidden in all the spectacle are a few playful touches of math that make this a classic example of math in movies done right.

The first comes in a short but funny scene with a simple fraction: “What is 60 ÷ 3?” On paper, it’s nothing special, but the way it plays out on screen—especially the grin on the kid’s face just before the train smashes into the wagon—turns a basic calculation into a moment of comedy.

Later, a sequence of numbers appears: 104 44 30 40 36 10. These turn out to be coordinates. The twist? The given coordinates (40°36′10″N, 104°44′30″W) don’t actually point to Devils Tower, the film’s famous setting, but to a farm paddock in Colorado—roughly 444 km south of the monument. The correct location should have been closer to 44°35′25″N and 104°42′54″W.

It’s a small slip, but one that makes the moment even more memorable. This is exactly why exploring math in movies is fun: even in a film about cosmic mystery, math sneaks in—sometimes precise, sometimes flawed, but always adding a new layer to the story.

War Machine: 10 – 2 = 20

David Michôd’s War Machine (2017), starring Brad Pitt, is one of those strange blends of comedy and tragedy: funny on the surface, but unsettling because of the subject it tackles—the war in Afghanistan. Maybe that’s why the film wasn’t warmly received, yet it still manages to deliver sharp insights into the absurdities of modern warfare.

One of its most memorable math moments comes in a comic lecture where Pitt’s character confidently explains that 10 – 2 = 20. The scene is ridiculous, but it works as satire—illustrating how logic can be twisted to fit a narrative, how numbers can be bent in service of authority.

The film also features the infamous PowerPoint slide, so convoluted that General Stanley McChrystal once quipped, “If I understand this slide, we’ll have won the war.” Together, these images paint a picture of politics, power, and the dangers of respecting appearances over substance.

As one of Netflix’s first large-scale productions, War Machine uses mathematics not as truth, but as theater. And that’s what secures its place in the long tradition of math in movies: sometimes equations don’t illuminate reality—they mock it.

The Ice Storm: Perfect Squares and Imperfect Worlds

Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm (1997) is remembered for its melancholy portrait of suburban life in the 1970s, but tucked within it is a surprisingly philosophical math moment. A character reflects:

“When they say 2 × 2 is equal to 4, it is not numbers, it is space. It is perfect space. But only in your mind. You cannot draw perfect squares in the material world.”

It’s a striking line, turning simple arithmetic into metaphysics. Mathematics here isn’t just about numbers, but about ideals—perfect forms that exist only in thought. In reality, every drawn square is flawed, every line imperfect.

This is what makes the scene so memorable, and why The Ice Storm deserves a mention in the tradition of math in movies. It shows how mathematics can slip from calculation into philosophy, becoming a meditation on perfection, imagination, and the limits of the physical world.

Hardware: Mandelbrot in the Wasteland

Richard Stanley’s Hardware (1990) has grown into a cult classic, mixing sci-fi, cyberpunk, and horror with a visual style that feels part Blade Runner, part Mad Max: Fury Road. The film’s mood is set by its striking desert imagery—opening and closing sequences painted in red skies that frame the dystopian chaos in between.

Amid its violence and grit, there’s also an unexpected mathematical touch: a Mandelbrot scene. The fractal imagery slips into the film as a moment of pattern inside disorder, geometry inside chaos. It doesn’t try to explain itself, but it adds a strange texture—reminding viewers that even in dystopia, mathematics haunts the frame.

That’s why Hardware earns its place in the catalog of math in movies. The Mandelbrot set, endlessly complex and recursive, fits perfectly with the film’s atmosphere: beauty inside horror, infinity lurking beneath the surface of decay.

Jane Eyre: Teaching Mathematics in Passing

In most adaptations of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, mathematics isn’t something you expect to find. Yet in one lighthearted carriage scene, Edward Rochester playfully imagines Jane teaching mathematics. It’s a fleeting moment, but it adds a tender, almost whimsical layer to their dynamic.

Here math isn’t presented as a blackboard struggle or a formal lesson, but as an image of stability, order, and everyday life—something Rochester half-jokes about as he teases Jane. The scene works because it’s ordinary, grounding the intensity of their relationship in the simple idea of teaching and learning.

It’s a small glimpse, but enough to give Jane Eyre a place in the broader catalogue of math in movies. Sometimes the presence of mathematics isn’t about the subject itself, but about what it represents: intimacy, imagination, and the promise of a shared future.

Breaking the Code: Enigma and Complexity

Breaking the Code (1996), adapted from Hugh Whitemore’s play, tells the story of Alan Turing, one of the most brilliant minds of the 20th century. The film follows both his groundbreaking work and his tragic personal life, portraying him as a man caught between genius, secrecy, and persecution.

At the heart of the story is the Enigma machine and the immense complexity of breaking its code during World War II. The film doesn’t drown viewers in technical detail but makes clear the staggering mathematical challenge: billions of possible configurations, a problem of combinatorics and logic that seemed unsolvable. Turing’s insight into computation and algorithms turned that chaos into something tractable—and laid the foundations for modern computer science.

In this way, Breaking the Code is one of the most direct examples of math in movies. It shows mathematics not as decoration, but as the very engine of history: equations and machines that changed the course of the war, and with it, the future.

Pain and Glory: Fluid Dynamics and Knowledge of Pain

Pedro Almodóvar’s Pain and Glory (2019) is one of his most poetic films—a meditation on memory, art, and the fragility of the body. Mathematics and science aren’t central, but they flicker briefly in two small moments.

One involves fluid dynamics images, glimpses of flow patterns that echo the film’s concern with movement, turbulence, and the difficulty of holding life steady. The other is a reflection on the knowledge of pain—not in a strictly scientific sense, but as an acknowledgment that suffering, like knowledge, shapes us in ways that resist measurement.

These fragments are subtle, but they add to the film’s texture. They remind us that even in a story about art and longing, mathematics and science hover in the background, quiet metaphors for how beauty and suffering intertwine. And that’s why Pain and Glory earns a gentle place in the broader tradition of math in movies—not for equations, but for the way images of science can deepen poetry on screen.

After the Dark: The Infinite Monkey Theorem

John Huddles’ After the Dark (2013) is built almost entirely out of thought experiments. A philosophy teacher challenges his class to play through apocalyptic “shelter” scenarios, forcing them to make decisions about value, purpose, and survival. It’s an ambitious premise—sometimes compelling, sometimes frustrating—and as critics have pointed out, the film stumbles badly toward the end. Still, its strongest moments are in the early sequences, when it leans on classic paradoxes.

One of these is the Infinite Monkey Theorem: the idea that if a monkey types randomly on a typewriter for an infinite amount of time, it will eventually produce the complete works of Shakespeare. The film pairs it with the Trolley Problem, using both as springboards to provoke debate about chance, choice, and morality.

These references give the story a sharper edge, hinting that without the grounding of mathematics and the sciences, philosophy risks collapsing into hand-waving. Even if the execution isn’t perfect, After the Dark earns a small place in the catalogue of math in movies for daring to mix abstract paradoxes with teenage drama—and for reminding us that infinity has teeth.

Real Genius: From Power Series to Bessel Functions

Martha Coolidge’s Real Genius (1985) is one of the classic nerd comedies of the 1980s, packed with lasers, pranks, and a campus full of overachievers. But unlike many movies that only gesture vaguely at academics, this one sprinkles in some actual mathematics.

Early classroom scenes feature real calculus content—first power series expansions, later even Bessel functions, the kind of advanced math most undergraduates never see outside a specialized course. The references aren’t explained in detail, but their inclusion gives the film a layer of authenticity, grounding its comedy in the genuine atmosphere of a top-tier technical university.

It’s a reminder of why Real Genius holds a fond place in the tradition of math in movies. Here, math isn’t the punchline—it’s the backdrop, part of the fabric of the story. Even as lasers fire and popcorn floods a house, the equations on the chalkboards are the real deal.

Equilibrium: The Mathematics of Gun Kata

Kurt Wimmer’s Equilibrium (2002) is remembered for its dystopian aesthetic and its stylized combat system known as gun kata. What makes gun kata interesting is that it’s not presented as pure choreography, but as something rooted—at least in the film’s logic—in mathematics.

The idea is that the movements of an armed opponent can be predicted through probability distributions. By analyzing countless past encounters, the system identifies statistically optimal positions from which to fire or evade. In other words, combat is reduced to data: a geometric dance guided by likelihoods.

Of course, the real science behind this is shaky at best, but as cinema it’s a fascinating touch. Gun kata becomes a metaphor for the attempt to turn chaos into order, violence into calculation. And that’s why Equilibrium finds its place in the landscape of math in movies—here, probability isn’t just theory, it’s weaponized.

Hidden Agenda: Mersenne Primes and Shadow Tracking

Marc S. Grenier’s Hidden Agenda (2001), starring Dolph Lundgren, is very much in the tradition of early-2000s action thrillers. The plot may feel closer to a TV movie than a blockbuster, but Lundgren—like Schwarzenegger, Stallone, Diesel, or The Rock—is the kind of screen presence you watch simply for the fun of it.

What makes this film unusual is its unexpected mathematical jargon. At various points, characters reference “crunching root permutations” and a Mersenne prime algorithm that supposedly makes “shadow tracking” more difficult. It’s techno-babble, sure, but surprisingly forward-looking. While Mersenne primes are famous for being connected to the search for the largest known prime numbers, they’re not commonly used in cryptography. And yet here they are, slipped into a 2001 action flick as if plucked from a mathematician’s notebook.

In hindsight, the script feels oddly prescient. A 2017 paper even tips its hat to this strange choice, suggesting the film deserves a little recognition for bringing prime numbers into the world of espionage action. For fans of math in movies, Hidden Agenda is a quirky gem: Dolph Lundgren battling villains while Mersenne primes hum in the background.

Amarcord: Quadratics in the Classroom

Federico Fellini’s Amarcord (1973) is a nostalgic tapestry of small-town life in 1930s Italy, full of eccentric characters, absurd humor, and bittersweet memory. Among its many delightful school scenes is a moment every student can relate to: struggling through mathematics.

Here, the task is to solve a quadratic equation. It’s brief, playful, and perfectly in tune with the film’s larger mood. Instead of focusing on abstract formulas, Fellini uses the math lesson as a stage for character quirks, classroom dynamics, and the universal awkwardness of learning.

The scene is one more reminder of how math in movies often functions—not just as content, but as atmosphere. In Amarcord, the quadratic isn’t about the solution on the blackboard, but about the texture of youth, memory, and the odd joy of school life.

Chaos Theory: A Movie Full of Math Moments

The 2008 film Chaos Theory, starring Ryan Reynolds, doesn’t shy away from numbers. Scattered throughout the story are little mathematical references that play into the film’s larger theme of unpredictability and control. From probability puzzles to playful logic, the movie sprinkles in moments where math becomes part of the narrative rather than just background detail.

One short clip captures this perfectly: a light, almost throwaway scene that still reminds us how math seeps into everyday life—even in a romantic dramedy. It’s not heavy-handed or overly technical, but it adds character, rhythm, and a wink to those who catch it.

That’s why Chaos Theory earns a place in the long, surprising tradition of math in movies—showing that even stories about love, chance, and timing can’t resist the pull of numbers.

The Thinning: Calculus and Linear Algebra on the Test

The Thinning (2016) is a dystopian teen thriller built on a chilling premise: every year, students are required to take a standardized test, and those with the lowest scores are literally executed—“thinned out.” While the story leans heavily on YA drama tropes, it does sneak in some actual mathematics.

On screen we catch glimpses of calculus and linear algebra: the product rule makes an appearance, as do simple linear equations. It’s quick, almost background detail, but it grounds the test in real mathematics rather than abstract “movie math.” Even more sci-fi is the addition of a special lens that can solve the problems in real time, underlining the role of technology as both savior and curse.

The math isn’t the focus—survival is—but these flashes make The Thinning another curious entry in the catalogue of math in movies. Here, calculus and linear algebra aren’t just classroom exercises; they’re matters of life and death.

Three O’Clock High: Algebra Before the Fight

Phil Joanou’s high-school cult classic Three O’Clock High (1987) is best remembered for its countdown to a brutal after-school fight—but tucked into the story is a small math moment. During a quiz, some algebra problems appear, and to figure out who cheated, one of the students is forced to solve two blackboard questions involving square roots.

The problems themselves are simple, but the scene adds a different kind of tension. Just before the looming showdown, the film pauses to remind us that in school, tests and equations can feel as intimidating as any fight in the parking lot.

It’s a small touch, but enough to earn Three O’Clock High a place in the long list of math in movies. Because sometimes solving square roots is the easy part—the real problem is dealing with the school’s toughest kid.

All Quiet on the Western Front: The Beauty of an Arithmetic Series

Lewis Milestone’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), adapted from Erich Maria Remarque’s 1929 novel, is a landmark anti-war film. Amid its stark depictions of life and death on the front, there’s an unexpectedly tender moment of mathematics.

A soldier, surrounded by mud and chaos, mentions the formula for the sum of an arithmetic series.

He calls it beautiful. And in a way, he’s right. The usual classroom formula for the sum of an arithmetic series can look messy, but expressed this way it feels elegant—almost poetic. The soldier’s version captures the intuition perfectly: the sum as a combination of a rectangle (area AAA) plus a triangle (nL/2nL/2nL/2).

It’s a fleeting line, but it resonates. Even in the middle of war, there’s a moment of clarity where mathematics becomes a source of order and beauty. That’s what makes this scene a remarkable entry in the long tradition of math in movies: it shows how, even at the front, numbers can still offer a glimpse of something eternal.

UFO: Math in the Signal

Ryan Eslinger’s UFO (2018) isn’t your standard alien flick full of explosions and glowing saucers. Instead, it builds its tension around mathematics—and quite a bit of it.

Throughout the film, the protagonist Derek (played by Alex Sharp) digs into a mysterious signal, and the tools he uses aren’t ray guns but equations. We see prime factorizations, simple one-variable linear equations (the classic Dreisatz), the fine-structure constant hidden in data, and coordinate decoding. On top of that, the film ventures into linear algebra territory with eigenvalues, eigenvectors, and even trivial solutions to systems of equations.

Another recurring theme is the myth that great mathematical discoveries belong only to the young, a pressure that Derek feels as he tries to prove himself. It’s rare to see a movie lean so heavily on real mathematical language, but UFO manages to make it part of the drama without turning into a lecture.

It may not be flawless as cinema, but as far as math in movies goes, UFO is one of the few that really tries to ground its story in the methods of the discipline. It’s a reminder that sometimes, numbers themselves are the alien language.

The Last Enemy: The Poincaré Conjecture

The BBC miniseries The Last Enemy (2008) mixes political thriller with mathematics in a way that feels both surprising and ambitious. In one scene, a theorem is brought up that turns out to be none other than the Poincaré conjecture—one of the great problems of mathematics.

For a century it stood unsolved, challenging the brightest mathematicians. Then, in the early 2000s, Grigori Perelman finally proved it, earning (and declining) both the Fields Medal and the Clay Millennium Prize. Dropping a reference to this landmark achievement inside a drama about surveillance, technology, and paranoia feels almost meta: it’s about complexity, hidden structures, and the difficulty of truly knowing the shape of things.

This is a rare case of math in movies (or in this case, TV) reaching for the very top shelf. Instead of fractions or coordinate tricks, it casually invokes one of the deepest breakthroughs of modern mathematics.

G.I. Joe: Rise of Cobra – Shadows and Latitude

In the middle of the high-octane action of G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra (2009), there’s a surprising nod to classical mathematics. A photograph is analyzed, and the shadow within it is used to determine the latitude of where it was taken.

The idea goes back over two thousand years to Eratosthenes, the Greek scholar who measured the Earth’s radius by comparing the angles of shadows cast by sticks at different locations. By applying the same principle, the film turns a simple visual clue into a geographic coordinate, blending modern espionage with ancient science.

It’s a brief moment, but a neat reminder of how timeless some mathematical tools are. Even in a blockbuster full of explosions and futuristic weapons, the logic of geometry holds its ground. And that’s exactly what makes this a fun entry in the catalog of math in movies—a trick as old as antiquity, repurposed for Hollywood spectacle

Skyfall: Rubik’s Cube Fighting Back

In Sam Mendes’s Skyfall (2012), the Bond universe collides with the aesthetics of cyberwarfare. One of the most striking visuals is a kind of metaphor: a Rubik’s Cube “fighting back.” Shapes twist and shift across the computer screen, making the threat look like a mathematical puzzle brought to life.

The scene also leans into classic hacker clichés. Linux terminals stream by, with “htop”-style process monitors flashing, and of course the trusty hex editor makes an appearance. For anyone who poked around in Atari game binaries back in the ’80s to swap out dialogue text, it feels oddly familiar.

And then come the flashy graph animations—visualizations reminiscent of examples from the Sigma library, turning code and data into pulsing, geometric art. It might not be mathematics in a strict sense, but it carries a mathematical flavor all the same. That’s why this sequence earns a quirky spot in the tradition of math in movies: a Bond moment transformed into a visual spectacle of puzzles, code, and numbers.

Catch-22: A Paradox on Duty

Joseph Heller’s 1961 novel Catch-22 (and the later film adaptation) is one of the sharpest critiques of military bureaucracy. At its core lies a brutally simple logical paradox: to be excused from combat duty, you have to be insane. But if you apply to be excused, that very act proves you’re sane—so you can’t be excused.

This closed loop of reasoning became the hallmark of the story, and the term “Catch-22” has since entered everyday language to describe situations that trap you in contradictions with no escape.

A side note: this clip was first flagged while preparing material for Math 22a, a vector calculus and linear algebra course. An amusing pairing—on one side, paradoxical logic with no solution, on the other, mathematics built on clarity, structure, and solvability.

Artificial Intelligence: Equations and the Meaning of Life

Steven Spielberg’s Artificial Intelligence: AI (2001) explores humanity’s search for identity and meaning through the lens of science fiction, and at one point the film directly touches on mathematics. A scene reflects on the fabric of space-time, noting how humans have sought the meaning of life in art, in poetry, and in mathematical formulas.

It’s a brief but weighty moment, connecting mathematics to humanity’s oldest questions. Equations and formulas appear not just as tools of science, but as part of the same drive that fuels art and literature: the attempt to make sense of existence.

That’s why Artificial Intelligence: AI earns its place among examples of math in movies. Here, math isn’t portrayed as mere calculation but as a philosophical pursuit—one more way humans wrestle with mystery, meaning, and the unknown.

The Killer Inside Me: Integrals in the Darkness

Michael Winterbottom’s The Killer Inside Me (2010) is a deeply unsettling film—an adaptation of Jim Thompson’s novel that explores the hidden violence of small-town deputy Lou Ford. The horror of the movie comes from the contrast: on the surface, Lou seems ordinary, calm, almost dull. Beneath, he is terrifyingly brutal.

Amid all this darkness, there’s an odd and fleeting scene: Lou quietly working out some integrals. The film never explains why a police officer is suddenly doing calculus, and the moment feels almost surreal. It’s as if, for a brief instant, logic and structure try to intrude into a story defined by chaos and cruelty.

That’s what makes this small touch so striking. In a movie where sanity is only an illusion, mathematics appears as a kind of anchor—a reminder of order, however fragile. It’s a tiny, unexplained detail, but enough to give The Killer Inside Me a peculiar place in the long catalogue of math in movies.

The Aeronauts: Graphs in the Sky

Tom Harper’s The Aeronauts (2019) dramatizes the record-breaking 1862 balloon flight of scientist James Glaisher, who set a new world altitude record. The film takes some liberties with the history, but it delivers a strong mix of spectacle, suspense, and period adventure.

Tucked into the action are small but clear nods to mathematics. The graph of a function h(t)—height as a function of time—is a staple of any single-variable calculus course, and here it becomes part of the storytelling. The rise of the balloon is not only a physical event but also something you can sketch as a curve, the ascent and eventual struggle mapped against time.

It’s a simple but effective reminder of how equations and graphs aren’t just abstract classroom exercises. In The Aeronauts, they echo the drama of exploration itself. That’s why the movie finds its way into the landscape of math in movies: the sky becomes both a frontier and a coordinate plane.

Cherry: Walking on Water

Cherry (2010) is one of those rare college films that manages to juggle romance, comedy, tragedy, and coming-of-age drama without losing its balance. The tone shifts easily between funny and serious, and the characters feel genuine and believable—never slipping into caricature. It’s a surprisingly honest story, which makes it easy to recommend.

Floating through the movie’s backdrop is an unexpected amount of physics literature. Equations and references flash by, anchoring the more grounded college drama to something bigger. And framing the whole story is an ambitious assignment from Professor Van Auken (played with just the right mix of deadpan and intensity by Matt Walsh—familiar from The Hangover and Old School). His challenge to the students is outrageous but inspiring: build a device that allows a human to walk on water.

It’s a perfect metaphor for the film itself—reaching past what seems possible, mixing the absurd with the sincere. And it’s also why Cherry earns a small but notable place in the long tradition of math in movies and science on screen. It reminds us that the classroom, with its impossible assignments and scribbled equations, is often the best stage for exploring both ideas and emotions.

Network: Money and Mathematics

Sidney Lumet’s Network (1976) is best remembered for its fiery speeches and sharp satire of television, but it also slips in a fascinating moment where mathematics meets capitalism. In a famous scene, Arthur Jensen (Ned Beatty) lectures the unhinged anchorman Howard Beale (Peter Finch) on the true primal force of nature: money.

“What do you think the Russians talk about? Karl Marx?” he asks. Then comes the punch: they don’t talk ideology, they run numbers. Jensen rattles off “linear programming charts, statistical decision theories, mini-max solutions,” describing how nations calculate prize-cost probabilities for their investments—just like the Americans do.

It’s a striking example of math in movies used not for education or comedy, but as a rhetorical weapon. Here mathematics becomes the cold, rational language of power, reducing politics and ideals to optimization problems. In Network, equations don’t just solve problems—they strip away illusions.

The Wild Blue Yonder: Chaotic Transport

Werner Herzog’s The Wild Blue Yonder (2005) is one of those films that blend reality and fiction in ways only Herzog dares to attempt. It combines documentary footage, staged sequences, and interviews—serious material reframed in such a strange context that it sometimes becomes unintentionally funny.

One of the highlights is an interview about chaotic transport in the solar system, featuring Martin Lo alongside two other mathematicians. The science itself is very real and deeply important—chaotic dynamics help explain how objects move unpredictably across gravitational fields. But placed inside Herzog’s surreal narrative about alien life and cosmic displacement, the conversation feels like both truth and parody at once.

It’s a perfect example of how math in movies can exist in unexpected forms. Here, mathematics isn’t a blackboard exercise but part of an earnest scientific discussion, refracted through cinema into something uncanny. In The Wild Blue Yonder, chaos theory leaves the textbook and drifts—quite literally—into space.

Flipped: The Area of a Rhomboid

In the film Flipped (2010), a tender love story about two teenagers seeing the world from very different perspectives, math briefly sneaks into the storyline. During one classroom scene, the teacher is explaining the area of a rhomboid, chalk in hand, laying out the formula on the board. The clip actually starts a little earlier, showing Juli Baker sitting at her desk, visibly absent-minded. She isn’t lost because the geometry is difficult—her distraction comes from being overwhelmed by her feelings for Bryce, the boy who is never far from her thoughts.

The juxtaposition is quietly funny. On the one hand, the teacher is methodically working through the certainty of mathematics, reducing the rhomboid to a simple formula. On the other, Juli is floating in the uncertainty of first love, where no rules seem to apply. The scene doesn’t dwell on math itself, but the presence of the rhomboid problem adds texture: a moment where the logical clarity of the classroom is disrupted by the emotional chaos of adolescence. It’s a small reminder that, for many students, the hardest part of learning isn’t the formulas on the board, but the storms in their hearts.

The Bank: The Compound Interest Formula

The Bank (2001) is an Australian thriller that mixes finance, technology, and morality. At its core is a brilliant mathematician who develops a formula capable of predicting movements in the stock market—a discovery with dangerous consequences once placed in the hands of powerful bankers. The film doesn’t shy away from showing mathematics directly: viewers catch glimpses of the multiplication table as part of the young prodigy’s early fascination with numbers, and later, the compound interest formula becomes a symbol of how simple math underpins massive financial systems.

These details aren’t just background—they highlight how mathematics can be both empowering and destructive, depending on who wields it. The multiplication table represents the innocence of learning, while the compound interest formula points to the machinery of greed that drives banks to exploit customers. By weaving these mathematical elements into its story, The Bank grounds its critique of capitalism in something concrete: the equations and formulas that most people learn as children, but rarely think about in the context of real-world power.

The Maltese Falcon: Mathematically Correct

John Huston’s classic The Maltese Falcon (1941) is a film built on riddles, schemes, and shifting truths. Much of its power comes from dialogue that bends logic back on itself—meta talk, meta-meta talk, and the kind of circular reasoning that keeps everyone off balance.

In one exchange about the black bird, the phrase “mathematically correct” slips in. It’s almost tossed away, but it lands with weight: logic and precision suddenly intrude into a conversation otherwise clouded by deception. The irony, of course, is that nothing in the world of The Maltese Falcon is truly precise—every character is twisting words to hide something.

It’s a small but telling example of math in movies working as more than just arithmetic. Here, “mathematically correct” becomes a meta-statement about truth itself—an anchor point in a story where almost nothing else can be trusted.

To Have and Have Not: Numbers Between the Lines

Howard Hawks’ 1944 film To Have and Have Not is a loose adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s novel, but what it’s really remembered for is the on-screen (and later off-screen) chemistry between Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.

The scenes don’t put mathematics front and center, but numbers linger in the background—fishing fees, gambling debts, who’s earning what and who’s losing it. Math here isn’t chalked onto blackboards; it’s woven into the everyday arithmetic of survival and chance.

That’s why To Have and Have Not earns a quiet place in the larger collection of math in movies. The numbers are subtle, overshadowed by love and adventure, but they’re always there—an invisible part of the story’s texture.

Contagion: Modeling the Outbreak

Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion (2011) has become one of those movies that suddenly felt eerily real in recent years. Among its many tense and unsettling moments is a scene that directly leans on mathematics: the modeling of a pandemic.

The dialogue touches on concepts like the basic reproduction number (R0) and how quickly a virus can spread through exponential growth. It’s presented with a chilling clarity—numbers that look dry on a blackboard translate into life-and-death stakes on screen.

This is math in movies at its most sobering. Instead of abstract puzzles or playful equations, the math here shows the raw, predictive power of models that can chart disaster in real time. In Contagion, the equations don’t just explain the crisis—they make you feel its inevitability.

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre: Fractions in the Dust

John Huston’s 1948 classic The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is a story of greed, trust, and betrayal. Alongside its tense drama and Humphrey Bogart’s unforgettable performance, the film also slips in a few small moments of mathematics.

As the gold prospectors argue over their shares, simple calculations and fraction problems appear. On the surface, they’re just about dividing treasure fairly, but they also echo the film’s central tension: once trust erodes, even the certainty of math can’t hold things together.

These little touches are why The Treasure of the Sierra Madre deserves a place in the world of math in movies. Here, mathematics isn’t about blackboards and formulas—it’s about survival, fairness, and the fragile arithmetic of human greed.

Ring: A Blackboard Disturbance

In Hideo Nakata’s Ring (1998), math sneaks into the horror. A mathematician’s blackboard is quietly tampered with—just a small change to a symbol. It looks harmless, almost trivial, but the alteration causes him real trouble later on. Not long after, he dies, becoming another victim of the cursed tape that drives the film’s story.

It’s a fleeting moment, but one that fits perfectly with the film’s unsettling atmosphere: the idea that even the precise, logical world of mathematics isn’t safe from corruption. A single mark out of place can unravel everything.

This is what makes math in movies so fascinating—you’ll find it in comedies, dramas, and even in horror films like Ring, where the distortion of a formula becomes part of the larger theme of inevitability and dread. Numbers can illuminate, but here they also haunt.

The Knack … and How to Get It: Angles of Reflection

Richard Lester’s 1965 film The Knack … and How to Get It is packed with Mod culture, absurd humor, and the restless energy of its era. And yet, right in the middle of all that chaos, a bit of mathematics slips in: “The angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection.”

On the surface, it’s just a basic rule of physics, but in this context it lands almost like a punchline. The precision of science collides with the film’s offbeat comedy, giving the scene an extra layer of irony.

Moments like this are what make The Knack a quirky entry in the world of math in movies. Mathematics and physics don’t always show up in cinema as grand theories or sprawling equations. Sometimes they appear as small, almost throwaway lines—reminding us that science is quietly embedded in the everyday, even in the middle of a 1960s comedy.

Drowning by Numbers: Counting the Stars

Peter Greenaway’s Drowning by Numbers (1988) unfolds like a puzzle stitched together with numbers. Little games, visual details, and repeating motifs run throughout the film. One of the most striking comes in a scene about counting stars.

“Once you’ve counted the hundred, all the others are the same,” the line goes. After the first hundred, the rest blur together. It’s a moment that feels both playful and philosophical: counting is a human attempt at order, but faced with infinity, the act eventually collapses into futility.

That’s what makes Drowning by Numbers such a curious entry in the world of math in movies. Here, math isn’t just about calculation—it’s a perspective, a way of looking at reality. Trying to count the stars becomes a metaphor for the human desire to measure, to grasp, to control. And in Greenaway’s hands, that desire becomes both a visual game and an intellectual challenge.

A Tiny Bit of Math in Dr. Zhivago

When you think about mathematics in movies, Dr. Zhivago is probably the last title that comes to mind. This is one of cinema’s great epics—snow, passion, revolution, balalaikas—not exactly a math lecture. And yet, just a few seconds before Yuri first lays eyes on Lara, the film slips in a curious little nod to mathematics. It’s gone almost as soon as it arrives, like a secret wink to anyone paying close attention.

The connection isn’t random. Pasternak’s original novel sprinkles mathematics in more deliberately. Shura Shlesinger is described as someone who knew a bit of everything, from mystical philosophy to mathematics, making her the go-to organizer for life’s important events. And then there’s Pavel Pavlovich, who dusts off his old passion for the exact sciences, teaching himself physics and mathematics at home to a level where he dreams of taking a degree in St. Petersburg.

It’s a reminder that mathematics in movies doesn’t always show up as chalkboard formulas or genius breakthroughs. Sometimes it hides in love stories, historical dramas, or even a fleeting moment before a life-changing encounter. In Dr. Zhivago, math isn’t the star of the show, but it still sneaks into the frame—quiet, unexpected, and strangely fitting.

The Clan of the Cave Bear: Counting Before Civilization

The Clan of the Cave Bear (1986), adapted from Jean Auel’s 1980 novel, pulls us back 25,000 years to a world where survival depended on instincts, rituals, and—surprisingly—numbers. In one striking scene, the young heroine Ayla reveals a gift for counting that far surpasses her clan’s abilities. Her mentor, Creb, patiently introduces her to the numbers three and five. Ayla doesn’t just learn them—she leaps far ahead, reaching ten, then twenty, with an ease that astonishes even him.

The beauty of this moment lies in its simplicity. No symbols, no tallies, no clay tokens—just fingers and pebbles. It captures a stage in human history when mathematics was nothing more than an intuitive sense of quantity, a tool for survival as natural as fire or stone tools.

And that’s what makes this scene fascinating. While most films showcase mathematics through blackboards or breakthroughs, here we see it in its rawest, most human form. It’s a reminder that long before equations and formulas, counting itself was revolutionary—and movies like this let us imagine what it must have felt like when someone first realized that numbers could stretch beyond what the eye could see.

Lambada: Complementary Angles on the Dance Floor

In the 1990 film Lambada, there’s an unexpectedly nerdy moment tucked into all the music and drama. Kevin Laird, a Beverly Hills schoolteacher with a secret double life, gives his students a lesson that goes way beyond the dance floor: the world of angles.

He explains the idea of complementary angles, points out “the most useful angle,” recalls the famous trigonometric identity cos²(x) + sin²(x) = 1, and even brings up the Cartesian coordinate system. While the movie is supposed to be about forbidden dance, this scene reminds us that math has a funny way of showing up where you least expect it.

What makes it charming is how naturally it connects movement with numbers. Dance relies on rhythm, symmetry, and patterns—the same foundations that drive mathematics. In its own quirky way, Lambada shows that steps and equations aren’t so different after all.