If you are a science person, have an appreciation for books, and love reading, then consider adding philosophy of science books to your reading list. Not only are these books entertaining, but they offer key insights into the world of science and can help deepen your understanding of the subject. That’s why, I have asked some science people and curated the very best 20 philosophy of science people books for you.

Philosophy of Science Books Help You Explore Different Perspectives

Philosophy of Science books can help you explore different perspectives on science. With these books, you can look at the concepts that shape scientific theories and ask questions about them. This can help you better understand how scientific ideas have developed over time and how they might change in the future. Plus, it’s always interesting to explore different interpretations and opinions outside your knowledge realm.

Expanding Your Knowledge

Reading philosophy of science books can also expand your knowledge on various science-related topics. Many philosophy texts deal with issues such as epistemology or ontology – two branches of philosophical thought that delve into the nature and limits of human knowledge – or even natural theology – which asks questions about how we understand God in a scientific context – all of which could help broaden your horizon when it comes to scientific matters. Even if you don’t agree with everything mentioned in these texts, by reading them, you will learn more about the different ways people think about certain science-related topics.

Gaining New Insights

Finally, reading philosophy of science books can provide insight into important topics that may not be discussed in other scientific texts. For example, many philosophers have written extensively on the ethical implications behind certain scientific experiments or projects, allowing readers to gain new perspectives and learn more about the ethical considerations involved in such activities. By reading these texts, readers can gain valuable insights into what goes on behind the scenes when conducting research or working on large-scale scientific projects.

In conclusion, reading the philosophy of science books offers many benefits for those who appreciate literature and learning about science-related aspects. These texts provide an opportunity for exploring different perspectives on various topics related to this field and allow readers to expand their knowledge base while gaining valuable insights into important matters that may not be covered elsewhere. If you are looking for an engaging way to learn more about this fascinating area, consider picking up some of these philosophy of science books today!

When you are done with this list, you may want to check out "23 Best Science Books You Should Read in 2023."Before you get started, I would like to suggest Audible for those of us who are not the best at reading. Whether you are commuting to work, driving, or simply doing dishes at home, you can listen to these books at any time through Audible.Proofs and Refutations by Imre Lakatos is a timeless classic that has never lost its applicability. The book analyzes numerous solutions to mathematical problems and, in the process, raises crucial questions regarding the nature of mathematical discovery and methodology. It takes the form of a debate between a teacher and some students.

Lakatos’ work continues to motivate mathematicians and philosophers who want to create a mathematics philosophy that considers both the static and dynamic complexity of mathematical practice. Lakatos demonstrates how mathematics improves through attempts at proof and critiques of these attempts. This book has been reissued for a new audience with a Preface by Paolo Mancosu that was expressly commissioned.

When it comes to statistics, we’ve all heard the phrase “correlation is not the same as causation.” But what does that really mean? Well, if two variables are correlated, it could mean that one causes the other, or maybe they both have a common cause. Figuring out the true cause and effect relationship can be tricky, especially when it’s not possible to conduct controlled experiments.

In “The Book of Why,” Judea Pearl offers a new perspective on causality. He introduces the use of graphical models to represent causal relationships between variables. By analyzing these causal graphs, we can determine if they align with the available data and develop strategies for controlling confounding variables. With this approach, Pearl takes us beyond simple associations and enables us to answer questions like “What would happen if we increased X?” or “How can we adjust X to get more of Y?”

But Pearl’s work isn’t just relevant to statistics and research. In the last chapter, he explores the implications of his approach for artificial intelligence (AI). While AI has made great strides using correlation-based statistical methods, Pearl argues that true AI requires incorporating causal inference. Without causal understanding, AI systems are limited.

“The Book of Why” is written for a general audience, making it accessible to anyone interested in causality. Pearl explains his approach using relatable examples from various fields, making the concepts easy to grasp. Additionally, the use of causal diagrams helps bridge the gap between technical and non-technical audiences.

It’s important to note that while “The Book of Why” provides an excellent introduction to Pearl’s approach, it may not be suitable as a textbook or reference guide. For readers seeking a more in-depth understanding, Pearl’s other works, such as “Causal Inference in Statistics: A Primer” and “Causality: Models, Reasoning and Inference,” offer more detailed explanations. Additionally, for those interested in alternative approaches, “Counterfactuals and Causal Inference” by Morgan and Winship is worth considering.

Overall, “The Book of Why” is a captivating exploration of the challenges of causality and an invaluable resource for those looking to delve into the world of causal inference.

What Is This Thing Called Science? brings Chalmers’ popular text up to date with contemporary trends and confirms its status as the best introductory textbook on the philosophy of science.

This revised and extended edition offers a concise and illuminating treatment of major developments in the field over the last two decades, with the same accessible style which ensured the popularity of previous editions. Of particular importance is the examination of Bayesianism and the new experimentalism, as well as new chapters on the nature of scientific laws and recent trends in the realism versus anti-realism debate.

How much faith should we place in what scientists tell us? Is it possible for scientific knowledge to be fully “objective?” What, really, can be defined as science? In the second edition of this Very Short Introduction, Samir Okasha explores the main themes and theories of the contemporary philosophy of science. He investigates fascinating, challenging questions such as these.

Starting at the very beginning, with a concise overview of the history of science, Okasha examines the nature of fundamental practices such as reasoning, causation, and explanation. Looking at scientific revolutions and the issue of scientific change, he asks whether there is a discernible pattern to how scientific ideas change over time and discusses realist versus anti-realist attitudes towards science. He finishes by considering science today and the social and ethical philosophical questions surrounding modern science.

Paul Feyerabend’s globally acclaimed work, Against Method, which sparked and continues to stimulate fierce debate, examines the deficiencies of many widespread ideas about scientific progress and the nature of knowledge. Feyerabend argues that scientific advances can only be understood in a historical context. He looks at the way the philosophy of science has consistently overemphasized practice over method and considers the possibility that anarchism could replace rationalism in the theory of knowledge.

This updated edition of the classic text includes a new introduction by Ian Hacking, one of science’s most important contemporary philosophers. Hacking reflects on both Feyerabend’s life and personality as well as the broader significance of the book for current discussions.

Discover the groundbreaking insights of Thomas S. Kuhn in his influential book, “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.” In this captivating read, Kuhn reveals his revolutionary perspective on how scientific knowledge progresses. He introduces the concept of paradigms, which encompass theories, research methods, and standards that define a scientific discipline. Through engaging in “normal science,” researchers refine these paradigms and solve puzzles within their field. However, as unexplainable anomalies accumulate, a crisis ensues, leading to a paradigm shift and a new way of comprehending the world.

Drawing upon historical examples from physics, chemistry, astronomy, and even geology, Kuhn showcases how past scientists approached questions and challenges in vastly different ways. From Aristotle and Newton to Einstein, these pioneers shaped the scientific landscape through their paradigm-shifting discoveries.

Kuhn’s work has popularized the buzzwords “paradigm” and “paradigm shift,” influencing the way we understand and discuss scientific advancements. Throughout his book, Kuhn illuminates three key insights.

Firstly, he highlights the novelty of unifying paradigms in scientific fields. Previously, scientists began with varied principles and ideas before gradually forming shared understandings and refining their pursuits. This shift allowed for specialized communication and progress within limited peer groups, contributing to science’s historical retreat to its ivory tower.

Secondly, Kuhn argues that scientists often cling to old paradigms, creating ad hoc explanations to maintain their validity. However, a new paradigm emerges and presents itself as a more fitting alternative, challenging the old ways of thinking. Kuhn likens this process to natural selection, where survival in the present takes precedence over achieving an ultimate goal. Convincing and converting others to embrace a new paradigm is a slow and human endeavor, with young scientists often at the forefront of novel ideas.

Lastly, Kuhn sheds light on the hidden and forgotten history of scientific revolutions. He critiques textbooks for glossing over the intricate and complex past of scientific disciplines, focusing solely on the current paradigm. This truncation of history fosters the misconception that science progresses linearly through accumulating facts, theories, and methods. Instead, Kuhn reveals that revolutions occur, rewriting textbooks and prompting scientists to approach problems from fresh perspectives.

With its readable prose and intellectually stimulating ideas, “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions” remains a timeless masterpiece by Thomas S. Kuhn. Join the ranks of those inspired by his groundbreaking theories and embark on a journey of scientific discovery.

Prepare to embark on a captivating journey through the annals of scientific discovery. “A Short History of Nearly Everything” defies convention, offering a narrative-driven approach that reads more like a thrilling story than a dry textbook. Author Bill Bryson’s conversational tone and informal style make for a refreshing and enjoyable reading experience.

What sets this book apart is its ability to demystify complex concepts without sacrificing depth. Bryson effortlessly explains the logic behind scientific breakthroughs, even shedding light on the origins of formulas used in A Level Physics. With humor and wit, he ensures that readers of all backgrounds can grasp each concept, leaving no knowledge assumption unaddressed.

Delving into the realm of past scientific endeavors, Bryson delves into the intriguing world of famous rivalries and the occasional misstep. Discover how scientists maneuvered to measure the distance between the Earth and the Sun, and enjoy tales of resilience amidst failure. Bryson expertly intertwines the personal lives of these brilliant minds, exploring the relationships between scientists and their often overlooked companions who aided them in their groundbreaking research.

From astronomy to geology, “A Short History of Nearly Everything” covers a wide range of scientific disciplines. Prepare to encounter mind-boggling concepts that have shaped our understanding of the world. I found it fascinating to learn about the eighteenth-century belief in the “élan vital” force, which attributed life to inanimate objects. Such peculiar ideas aside, A Short History of Nearly Everything presents countless foundational discoveries that form the bedrock of modern science.

Structured chronologically, each chapter seamlessly connects one scientific breakthrough to the next. This approach provides a comprehensive understanding of how each discovery builds upon its predecessors. As I journeyed through the pages, I gained a profound appreciation for the importance of contemporary research, fueling my excitement to apply to a prestigious university renowned for its scientific endeavors.

Whether you have a general interest in science or are specifically applying to Chemistry, Physics, or Earth Sciences, “A Short History of Nearly Everything” is a must-read. This book will not only satisfy your curiosity but also shed light on the “why” behind scientific inquiries. Let it ignite your passion and inspire you to embark on your own scientific odyssey at the University of Oxford.

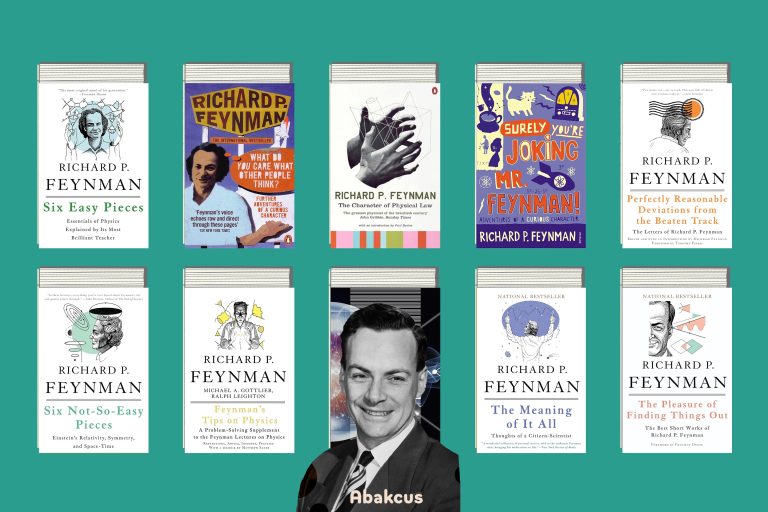

The legend of Richard Feynman continues to captivate us even after his passing. With “the best short works of Richard P. Feynman,” The Pleasure of Finding Things Out offers a diverse range of his writings, shedding further light on the mind of this brilliant and unconventional scientist.

Included in this collection are interviews, lectures, reminiscences, and even Feynman’s minority report on the Challenger inquiry. From personal anecdotes to technical pieces, The Pleasure of Finding Things Out provides an excellent introduction to Feynman, showcasing his inquisitive mind, his wit, and his genius.

While some of the writings may seem haphazard, this variety allows readers to fully appreciate the many facets of Feynman. Descriptions of his youth, where he discovered “the pleasure of finding things out,” and his insatiable curiosity about the world give a vivid glimpse into the man behind the accomplishments.

Whether discussing his experiences in Los Alamos, exploring cult sciences, or contemplating the future of technology, Feynman’s curiosity and skepticism shine through. The Pleasure of Finding Things Out is filled with captivating anecdotes and thought-provoking speculations that keep readers engaged and constantly looking ahead to the next idea.

However, it is important to note that the book‘s directness can also be its weakness. The prose is unpolished, with transcriptions of lectures and interviews lacking in clarity. A stronger editorial hand could have improved the readability and provided clearer introductions and attributions.

Despite these flaws, Feynman’s generous spirit permeates the pages, making the journey through occasionally muddled prose worthwhile. Many of his insights, even decades later, remain relevant and thought-provoking. The Pleasure of Finding Things Out is a recommended read, with the caveat that readers should not expect a perfectly polished experience.

Editorial mistakes in the American edition, such as incorrect information about Brownian motion and a misspelling of James Joyce’s work, are unfortunate and should have been avoided. It is our hope that future editions will address these issues.

Phi: A Voyage from the Brain to the Soul is a really good read. From one of the most original and influential neuroscientists working today comes a unique look at consciousness, as told by Galileo, who made it possible for science to be objective and now wants the subjective experience to be part of science as well.

Galileo’s trip comprises three parts, and a different person leads each one. In the first, he learns, with the help of a scientist who looks like Francis Crick, why some parts of the brain are more important than others and why consciousness fades when you sleep. In the second part, when his friend seems to be named Alturi (Galileo is hard of hearing; his friend’s real name is Alan Turing), he sees how the facts he collected in the first part can be explained by a scientific theory that connects consciousness to the idea of integrated information (also known as phi). In the third part, he sits with a man with a beard who can only be Charles Darwin and thinks about consciousness as an ever-growing awareness of ourselves in history and culture. He says that consciousness is everything we have and everything we are.

Since Godel, Escher, and Bach, there hasn’t been a book with such a unique mix of science, art, and imagination. The way we think about ourselves and the world will change because of how beautiful and interesting this story is.

Described by the philosopher A.J. Ayer as a work of ‘great originality and power’, this book revolutionized contemporary thinking on science and knowledge. Ideas such as the now legendary doctrine of ‘falsificationism’ electrified the scientific community, influencing even working scientists, as well as post-war philosophy. This astonishing work ranks alongside The Open Society and Its Enemies as one of Popper’s most enduring books and contains insights and arguments that demand to be read to this day.