Some stories in science don’t just tell us what was discovered, but also what it cost to make those discoveries. Marie Curie’s radioactive notebooks are exactly that kind of story. Today, they are stored in lead-lined boxes in Paris and London, untouchable without gloves, accessible only after signing liability waivers. These notebooks are far more than a romantic scientific relic. They are the birth pains of modern physics, living proof of why laboratory safety exists, and a quiet but persistent reminder of what “sacrifice for science” actually means. Marie Curie’s radioactive notebooks are, quite literally, a legacy that defies time.

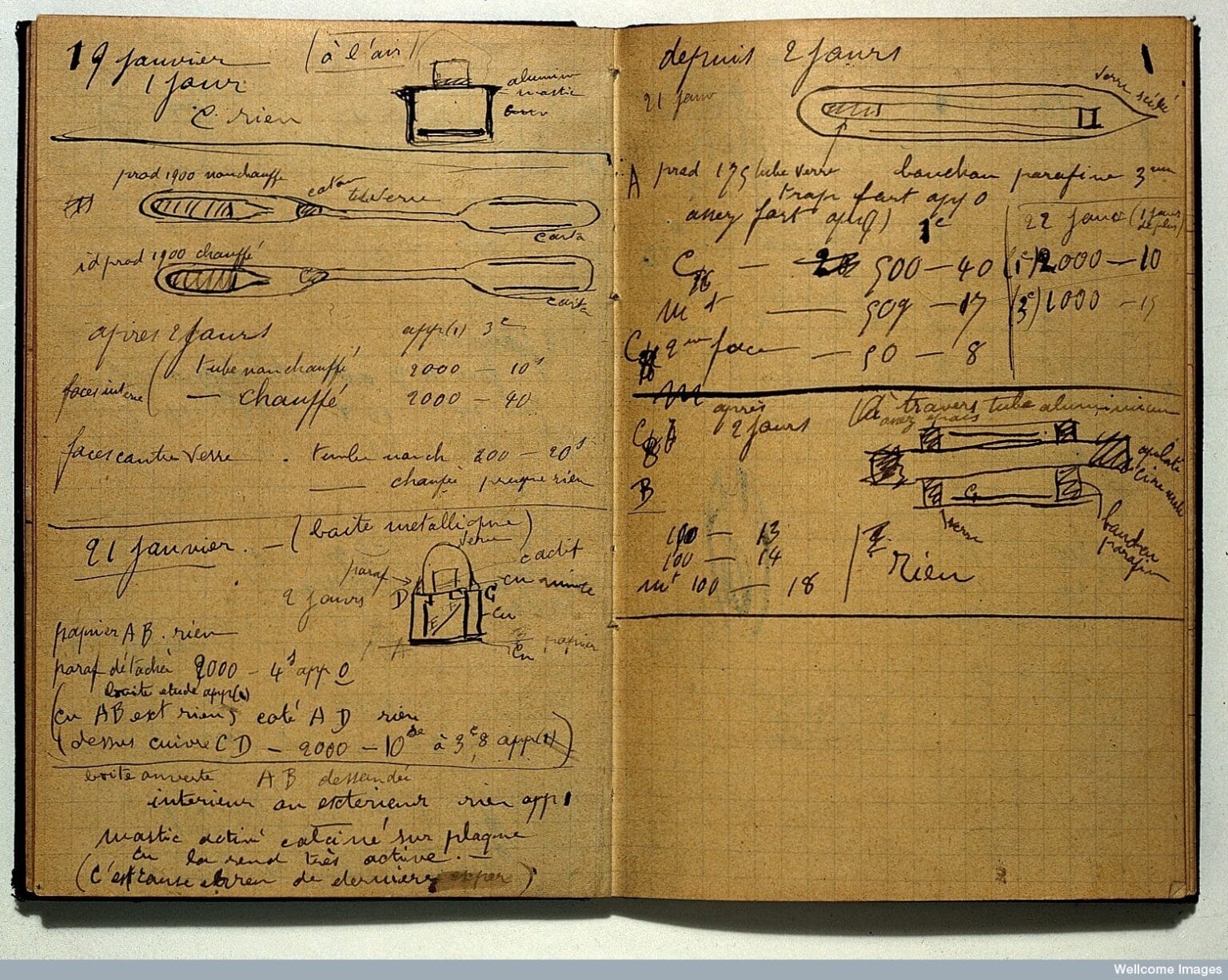

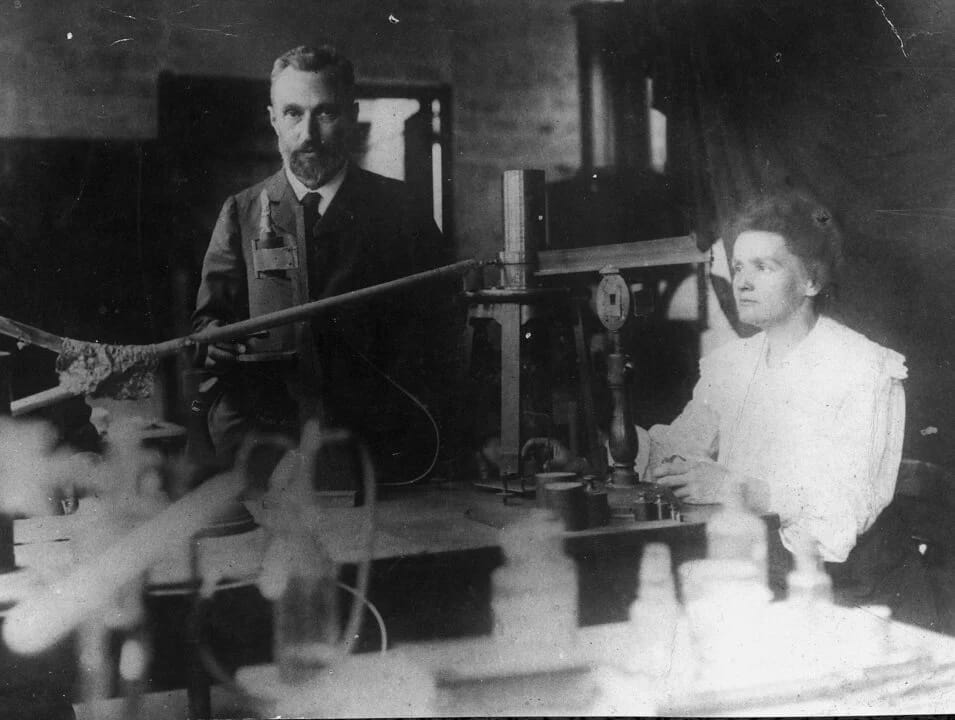

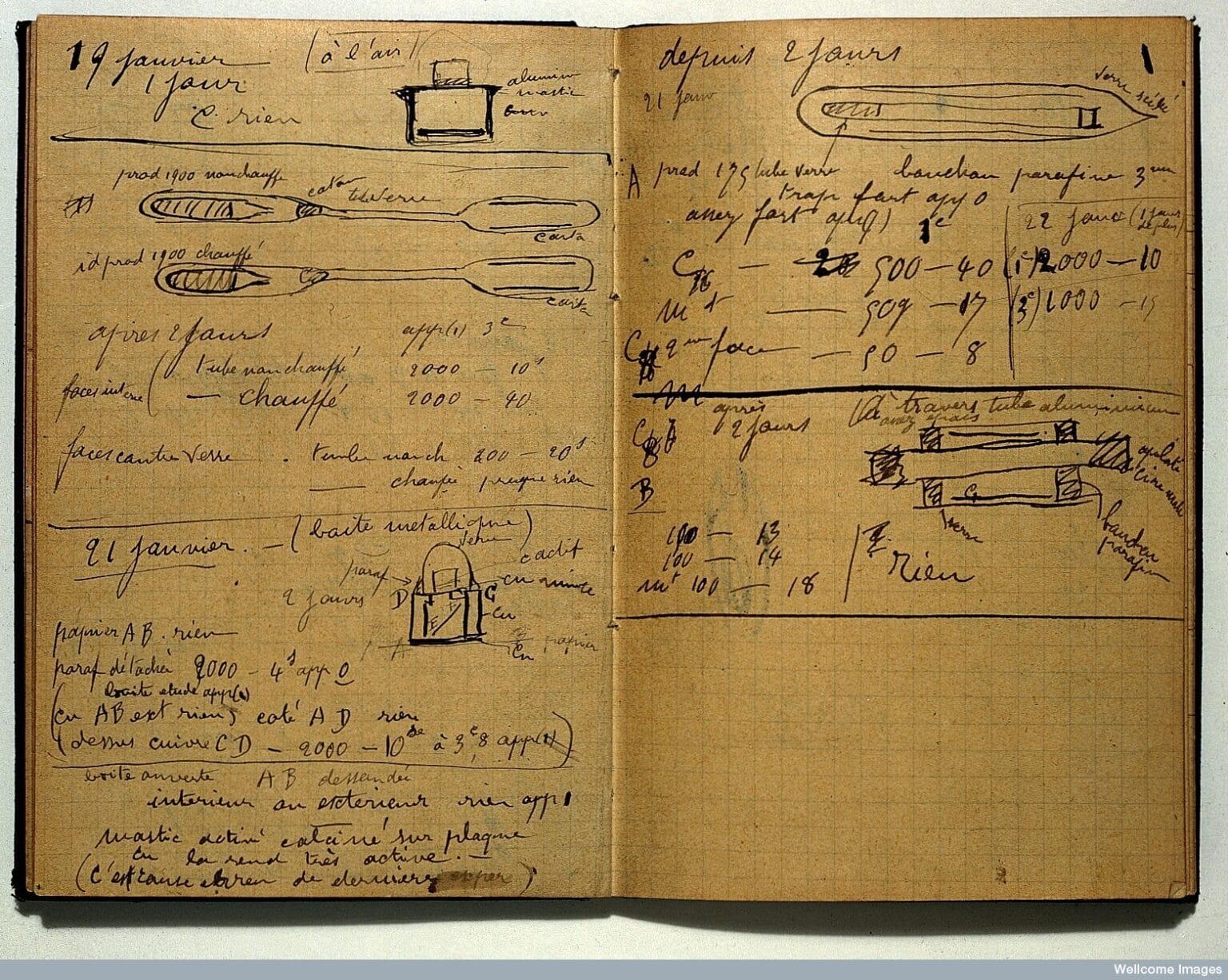

To understand this story, we need to return to the late nineteenth century. Radioactivity had just been discovered, the atom was still believed to be indivisible, and laboratory safety was essentially nonexistent. Marie and Pierre Curie followed up on Henri Becquerel’s observation that uranium salts emitted mysterious rays. But this was not the kind of work we imagine today, with sterile labs and digital instruments. They processed tons of uranium-rich pitchblende, grinding, boiling, and separating it by hand. It was physically exhausting, repetitive labor that went on for days and weeks. The resulting substances were stored in desk drawers, sometimes even carried in coat pockets. At night, bottles in the laboratory glowed with a faint blue-green light. Marie Curie later described this glow as beautiful, almost magical.

The problem was that no one knew what that glow really meant. The biological effects of radiation were completely unknown. Radiation was seen as a curiosity, even something beneficial. In those years, radioactive substances were added to toothpaste, drinking water, cosmetics, and all kinds of consumer products. Nobody stopped to ask whether this was a bad idea. Marie Curie’s radioactive notebooks were written in exactly this environment: bare hands, bare desks, bare paper. As she took notes, she left not only ink on the pages, but radioactive isotopes as well.

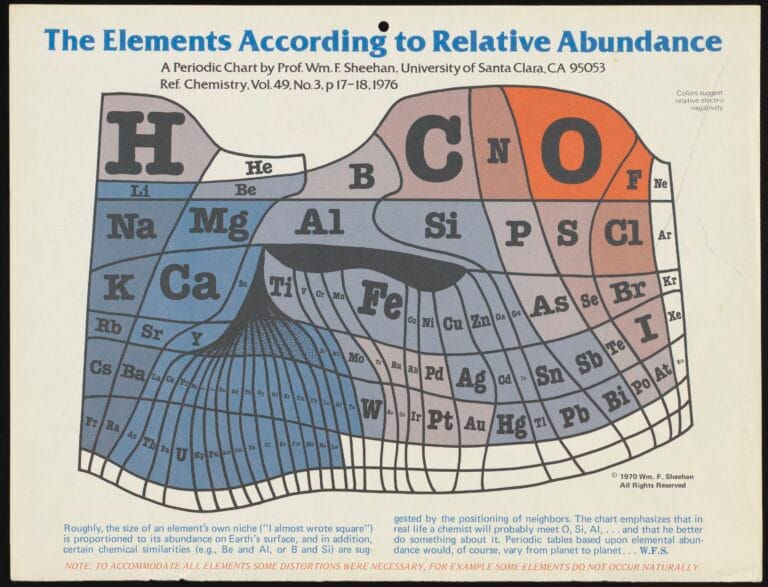

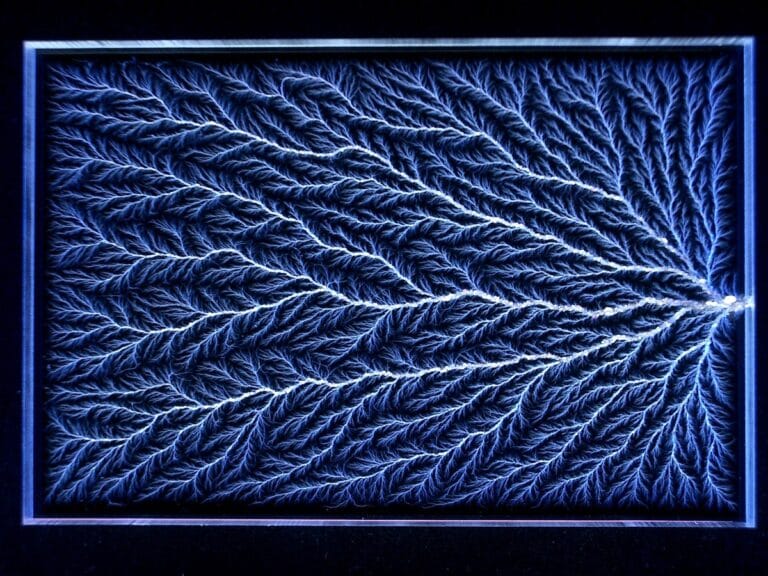

The main reason these notebooks are still considered dangerous today is radium-226. Radium was one of the Curie’s most important discoveries, and also the most stubborn. Its half-life is about 1,600 years. That means it takes 1,600 years for its radioactivity to drop by half. Marie Curie’s notebooks are just over a century old, which, in nuclear terms, makes them practically newborns. The radium is still there, embedded in the paper, still emitting measurable radiation.

This is where an important distinction is often lost: radioactive does not automatically mean deadly. The fact that the notebooks are radioactive does not mean they are comparable to nuclear waste or a bomb. Measurements show microcurie-level amounts of radium-226 on the covers and pages. These levels are easily detected by modern instruments, but they are modest when compared to many natural sources of radiation. Granite, old luminous watch dials, and even the human body itself emit small amounts of radiation.

That said, this is not something to be dismissed lightly. The real concern is contamination rather than simple exposure. Radium primarily emits alpha particles. Alpha radiation cannot penetrate skin, but it becomes dangerous if inhaled or ingested. This is why gloves are mandatory and dust exposure must be avoided. When libraries take extreme precautions, they are not being dramatic; they are responding to lessons learned at great human cost.

Marie Curie’s Radioactive Notebooks: Myth, Physics, and Real Risk

The phrase Marie Curie’s Radioactive Notebooks sounds like the title of a science fiction novel, and popular culture has happily amplified that tone. But once we look at the physics, the picture becomes clearer. Under controlled conditions, these notebooks do not pose a serious health risk to researchers. Turning pages or examining them briefly, following modern safety protocols, does not result in a meaningful radiation dose. The idea that touching them is instantly lethal belongs more to internet folklore than to science.

What truly matters is why these notebooks ended up this way, and what they represent. They are the documentation of one of the most expensive learning processes in scientific history. Marie Curie and Pierre Curie unknowingly made their own bodies part of the experiment. Marie Curie died in 1934 from aplastic anemia, a disease linked to long-term radiation exposure. Pierre Curie died earlier in a street accident, but he too lived with the effects of radiation for years. Both were buried in lead-lined coffins. That detail alone says everything: the people who illuminated the atom ultimately had to be shielded from their own discoveries.

The irony is that today, the notebooks are safer than they ever were during Marie Curie’s lifetime, because we now understand what we are dealing with. Marie Curie did not. Her notebooks are not just scientific records; they are physical proof of the price of ignorance. In that sense, they are the ancestors of every radiation safety rule and laboratory protocol we now take for granted.

This story also puts a quiet brake on the romantic image of science. The phrase “sacrifice for science” sounds noble, but Marie Curie’s radioactive notebooks force us to confront what that sacrifice actually involved. Without her work, modern medicine, radiology, and cancer treatment would not exist in their current form. But that progress came through real bodies, real damage, and real loss. The radiation embedded in those pages is a stubborn reminder of that fact.

Today, when a researcher in Paris asks to see those notebooks, the ritual is almost symbolic. Forms are signed. Gloves are put on. A lead-lined box is opened. It is a moment that captures the responsibility that comes with knowledge. Marie Curie’s notebooks carry not only the past, but a warning for the future: scientific progress is inevitable, but how we pursue it matters just as much as where it leads.

Perhaps that is why Marie Curie’s Radioactive Notebooks remain so compelling. There is nothing abstract here. No equations, no diagrams, no metaphors. Just paper, ink, and radiation you can measure. Locked inside lead boxes, these notebooks whisper the same message they have carried for over a century: sometimes, science really is untouchable. And it will remain that way for the next thousand years.