Electricity usually enters our lives through a wall socket, turns on a light, charges a phone, and we end our relationship with it right there. We want it quiet, invisible, and preferably trouble-free. But the truth is, electricity is nothing like that. Even when controlled, it still carries something wild, impatient, and slightly ill-tempered inside. Lichtenberg figures are precisely the visual confession of that character, delivered in a fraction of a billionth of a second. It is the moment electricity says, “this is who I really am.”

This piece is a bit science, a bit art, and a bit of that feeling that makes you ask, “who was the first person to even think of this?” Because what we are looking at is not a drawing, and definitely not a design. These patterns are not planned, sketched, or tweaked in Photoshop. Electricity does whatever it wants, and we simply observe the result.

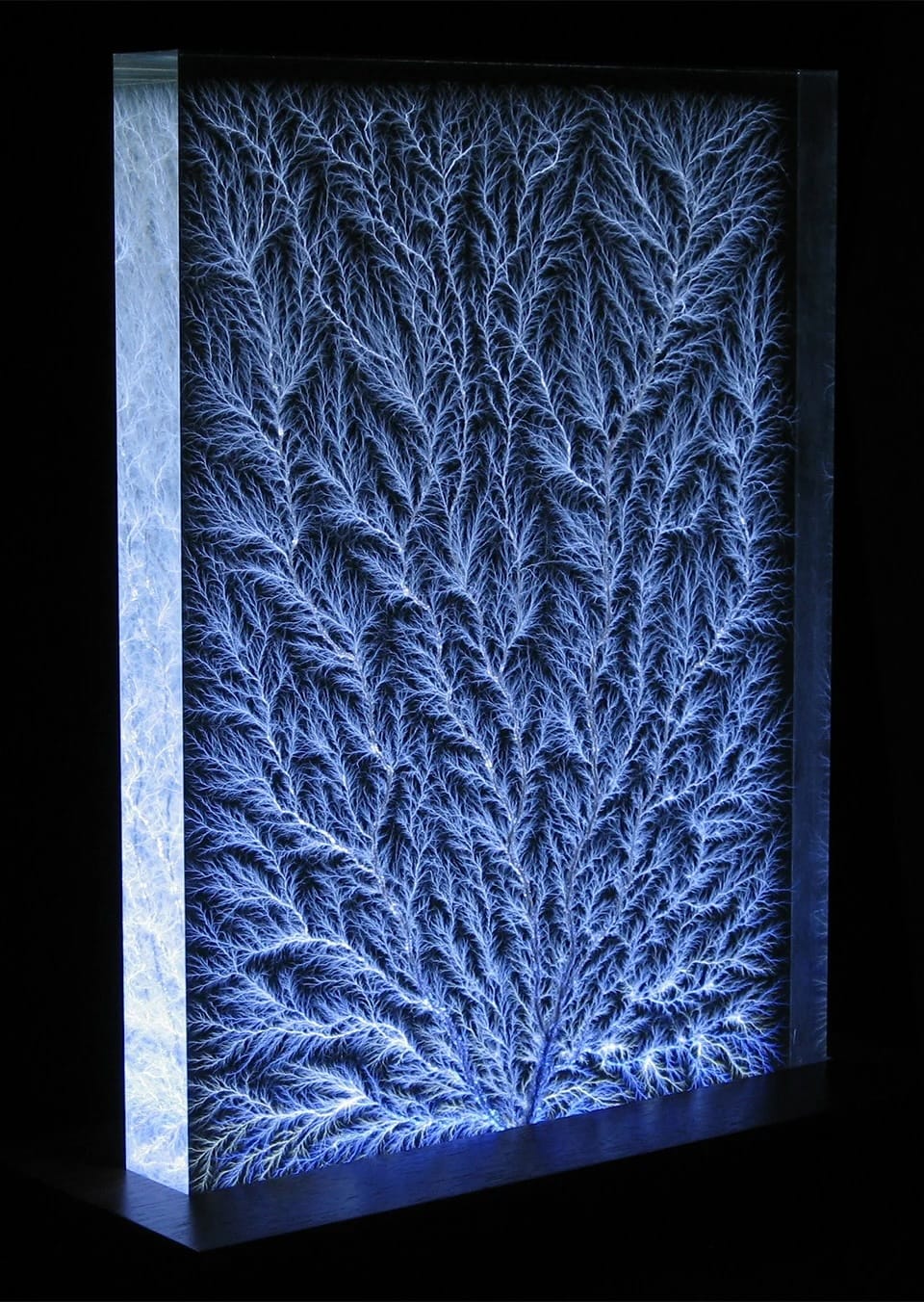

At first glance, it looks like the roots of a tree. Look again and it resembles lightning. Look closer and you start seeing blood vessels, river deltas, even neural networks. That is no coincidence. Nature tends to solve the same problem in similar ways at different scales. The shortest path, the least resistance, the fastest escape. Electricity is not exempt from this instinct.

The scientific name of these patterns is Lichtenberg figures. The name may sound academic, but the result is deeply intuitive. When electricity gets trapped somewhere, builds up, and is finally given a way out, it reveals its true nature. And when it escapes, it does not move in a straight line. It branches, splits, hesitates, and changes its mind, like a restless but extremely impatient brain.

This story goes back to the eighteenth century. When the German physicist Georg Christoph Lichtenberg noticed strange, branching dust patterns formed by static electricity during his experiments, he had effectively captured the choreography of electricity for the first time. Back then, these patterns were rare, fragile, and temporary. You could see them, and then they were gone. Today, that has changed. We can now make that moment permanent.

In the modern version, acrylic takes the stage. A clear, innocent-looking material we usually see in display cases or on desks. But when that block meets millions of volts of electricity, it turns out to be anything but innocent. Trillions of electrons are injected into it. From the outside, it looks like nothing is happening. Inside, however, an enormous tension is building. Electricity is waiting. Growing impatient.

Then someone introduces a tiny, deliberately weakened escape point. For electricity, this is not an invitation; it is an emergency exit. If you want to actually see this moment rather than just imagine it, there is a short video where Bert Hickman quite literally paints with lightning bolts.

You watch a multimillion-volt electron beam being driven into a clear acrylic block, and the abstract explanation suddenly becomes very concrete. The lightning does not politely follow a line; it hesitates, branches, and commits in real time. The video makes one thing very clear: what looks like a carefully composed artwork is in fact a split-second physical event, unfolding too fast for the human eye but slow enough for the camera to reveal its raw structure. At that moment, a microscopic lightning storm erupts inside the acrylic. Everything happens unbelievably fast. Faster than the blink of an eye. But the cracks, channels, and branches formed at that speed become permanently frozen inside the material.

Is the result a sculpture? Technically, yes. But there is no hand shaping it. The artist’s role here is not to hold a brush, but to set the conditions correctly. Voltage, direction, material, patience. Electricity takes care of the rest. That is why there is no such thing as “another identical one.” Even under the same conditions, the result changes. Because electricity chooses a different path every time.

Why do Lichtenberg figures feel so familiar?

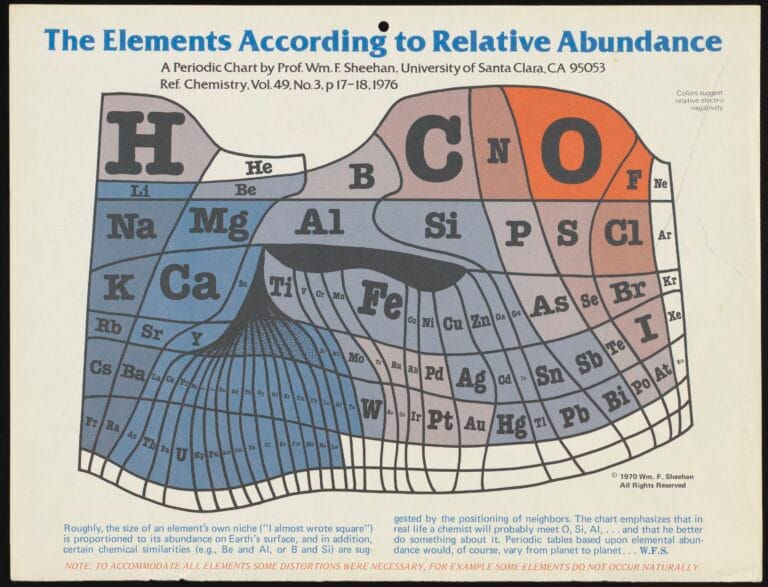

The answer lies in mathematics and nature. Lichtenberg figures are a perfect example of fractal structures, patterns that repeat themselves at different scales. You look at the large branches, then the smaller ones, then even smaller ones. The logic remains the same; only the scale changes. We see the same principle in trees, lungs, vascular systems, and even in the large-scale structure of the universe.

For electricity, the problem is simple: find the path of least resistance. But that path is never a single line. Along the way, countless micro-decisions are made. “Should I go here, or there?” The sum of those decisions creates this complex yet strangely ordered structure. That is why it feels both chaotic and organized at the same time. Because it is both.

If these patterns were drawn with lasers, they would still be impressive, but they would feel lifeless. Because there would be intention, planning, and repeatability. Here, there is no undo. Once electricity passes through, it leaves a scar. Much like life itself. In that sense, Lichtenberg figures are also physical memory records.

One of the most fascinating aspects is that the finest tips of these patterns are thought to extend down to the molecular scale. So what you are looking at is not just an aesthetic surface, but a story that reaches deep into the internal structure of matter. A process flowing from the visible to the invisible, from large to small.

When lighting is added, the effect becomes something else entirely. Light introduced from below refracts and reflects through these microscopic channels, making the patterns appear as if they are glowing from within. That is why these works look great in photographs, but feel entirely different in person. There is no movement, yet there is depth. Like a frozen explosion.

All of this serves as a reminder that science is often presented as cold, distant, and filled with formulas. Nature itself, however, is visual, intuitive, and often dramatic. Lichtenberg figures are among the clearest proofs of that. Electricity here is not just energy; it is a storyteller.

Perhaps that is why we cannot stop looking at them. They say something without using words. “This is how I work,” nature tells us. No more, no less.

In the end, what we are left with is neither just an art object nor a dry physics experiment. We are standing at that rare and valuable intersection between the two. We are given a brief glimpse into the inner world of electricity. And we realize that the things we think we control are often simply allowing us to watch.