There are some geometry books that make you think, the moment you open the cover, “someone really thought this through”; they are not written just to be read, nor printed merely to sit on a shelf. The mathematician’s obsession with order, proof, and structure meets the designer’s fixation on form, proportion, and visual balance in exactly these kinds of books. What you feel at first glance is that nothing inside is accidental; everything rests on a deliberate structure.

Mathematics and design have been speaking the same language for much longer than we tend to realize: geometry, symmetry, repetition, space, proportion, and intuition. One side calls them theorems, the other calls them grid systems, but they are looking at the same thing. That is why the books in this piece do not neatly separate into “math books” or “design books”; they sit comfortably in both worlds, books that make you put the pen down, linger on a single page, and slow your thinking.

Some turn equations into lines, others turn patterns into ideas, and some transform mathematics into something not just to be read but to be looked at. What these books share is a refusal to merely explain information; they make it visible. They invite a kind of thinking that works while reading and while looking.

If you love numbers but cannot give up beautifully designed books, or if you work in design but want a solid structure underneath, this list draws directly from that shared vein. We are after books that quietly yet convincingly remind us that mathematics and design are born from the same taste, even if they speak in different words.

The First Six Books of the Elements of Euclid — Oliver Byrne

The First Six Books of the Elements of Euclid is not a reinterpretation of Euclid so much as a radical redesign of how mathematical thought can appear on the page. Byrne replaces letters with color—primary reds, blues, and yellows—turning proofs into visual sequences rather than symbolic puzzles. The effect is immediate: geometry becomes something the eye can follow without constantly jumping between text and diagram. What was once austere and abstract suddenly feels readable, even playful, without sacrificing rigor.

The book’s lasting power lies in how quietly modern it feels. Long before modernist design movements embraced reduction and color as structure, Byrne treated layout itself as part of the argument. This is not a book you read quickly, nor one that explains itself in contemporary terms; it asks the reader to slow down and think visually. For mathematicians, it offers a reminder that proof is as much about perception as logic; for designers, it stands as an early demonstration that clarity, constraint, and visual hierarchy can fundamentally change how ideas are understood. Few books sit so comfortably at the intersection of mathematics, design, and pedagogy.

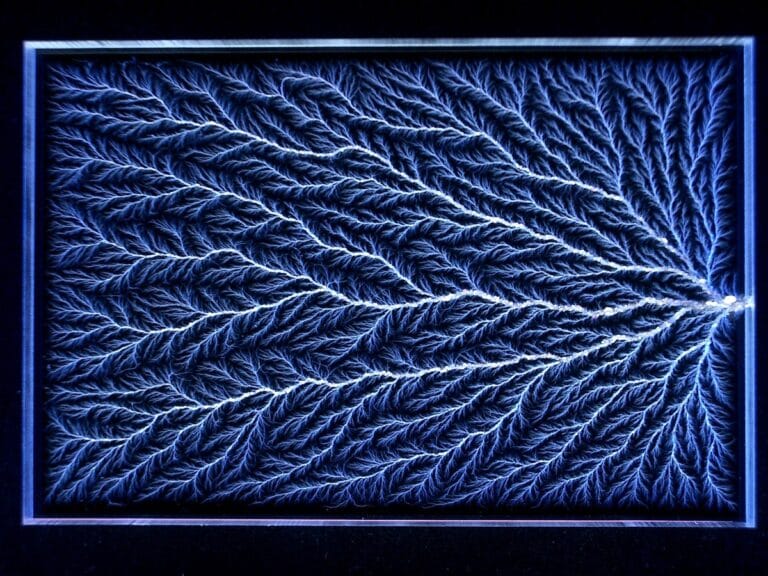

The Fractal Geometry of Nature — Benoît B. Mandelbrot

The Fractal Geometry of Nature speaks from places classical geometry quietly fails to reach. Mandelbrot’s core claim is simple yet unsettling: clouds are not spheres, mountains are not cones, and coastlines cannot be explained by smooth curves. The forms of nature are not merely “more complex,” but complex in a fundamentally different way, and the language of that complexity is fractal geometry. Throughout the book, repeating yet never identical structures make the tension between scale, randomness, and order gradually visible.

This is not a book written to be read linearly; in fact, it behaves like a fractal itself. Topics branch out, loop back, drift into other fields, and then return toward the center. The formulas grow dense at times, but the real strength of the book lies in how shapes carry the thinking. Mandelbrot turns mathematics from a tool for calculation into a way of seeing nature. For mathematicians, the book stands as both a manifesto and a historical turning point; for designers, it is an essential reference for understanding why irregularity can feel so convincing—and so right.

The Visual Display of Quantitative Information — Edward R. Tufte

The Visual Display of Quantitative Information is a stern yet instructive reminder that drawing graphs is not an act of decoration, but an intellectual responsibility. Tufte’s concern is clear from the start: the goal is not to beautify data, but to show the truth. Graphics, he argues, exist not to attract attention, but to make thinking easier. For that reason, the book relentlessly strips away unnecessary lines, embellishments, and every form of visual noise he famously calls “chartjunk.”

The book remains influential today because the issue is not the tools we use, but the way we look. Although Tufte begins with paper-based graphics, the principles he defends resist time: data density, honest scales, and trust in the reader. Graphics, he insists, should not simplify reality, but make complexity accessible. For mathematicians, the book reads like a manifesto of visual ethics; for designers, it offers a clear compass for where the line between aesthetics and truth should begin.

Pasta by Design — George L. Legendre

Pasta by Design answers the question of what mathematics is doing in the kitchen before it even needs to be asked. Legendre approaches pasta shapes not as recipes or cultural stories, but as pure problems of form: curvature, torsion, surface, volume, and repetition. Each type of pasta is treated almost like an engineering drawing, read through mathematical descriptions, axes, and proportions. What emerges is not a cookbook, but a visual investigation showing how a familiar everyday object can contain a surprisingly sophisticated geometric problem.

The book’s greatest strength lies in how it plays with seriousness. The subject is pasta, yet the approach is rigorously disciplined—playful without ever being lightweight. Pasta by Design pulls mathematics out of abstraction and turns it into something tangible, even edible. For mathematicians, it is a clever reminder of how unexpectedly form can appear; for designers, it stands as a rare example of how function pressures—and ultimately shapes—form.

The Geometry of Pasta — Caz Hildebrand & Jacob Kenedy

The Geometry of Pasta treats food not as something to be photographed, but as something to be analyzed. Hildebrand’s stark black-and-white illustrations strip pasta of culinary romance and present each shape as a geometric object: sections, profiles, thicknesses, voids. The result feels closer to an engineering manual than a cookbook. Pasta here is defined by how it bends, holds sauce, traps air, and repeats—form driven entirely by function.

What makes the book distinctive is its refusal to explain too much. The text is precise but restrained, allowing the drawings to carry most of the thinking. Recipes are present, but they feel secondary to the structural logic behind why a certain shape demands a certain sauce. For mathematicians, the book reads as a quiet study in applied geometry and optimization; for designers, it is a reminder that some of the most successful forms emerge not from expression, but from constraint. The Geometry of Pasta ultimately shows that even the most ordinary objects can reveal deep design intelligence when looked at closely.

Islamic Geometric Patterns — Eric Broug

Islamic Geometric Patterns treats geometry not as ornament, but as a disciplined method of construction. Broug approaches pattern-making through the most elemental tools—ruler, compass, and repetition—showing how complex visual systems emerge from simple geometric decisions. The book patiently walks through the logic behind stars, grids, and tessellations, making it clear that these patterns are not decorative accidents but carefully reasoned structures. Geometry here is procedural: each step builds necessity into the next.

What makes the book compelling is its emphasis on making rather than merely observing. Broug does not frame these patterns as distant historical artifacts; he presents them as reproducible systems that reward precision and attention. For mathematicians, the book offers a concrete demonstration of symmetry, tiling, and constraint in action; for designers, it reveals how richness can arise from strict rules rather than expressive freedom. Islamic Geometric Patterns ultimately shows that repetition, when governed by structure, is not limiting but generative.

The Polyhedrists: Art and Geometry in the Long Sixteenth Century — Noam Andrews

The Polyhedrists treats geometry not as a finished system, but as a living, experimental practice shaped by artists as much as by mathematicians. Andrews follows a loose collective of early modern figures—Pacioli, Dürer, Jamnitzer, Stöer—who treated polyhedra not as textbook solids, but as objects to be stretched, distorted, embellished, and tested against material reality. In their hands, geometry becomes a workshop activity: something drawn, carved, printed, and assembled, rather than merely proven.

What makes the book compelling is its refusal to frame these works as historical curiosities or naive precursors to “real” mathematics. Andrews shows how the explosion of irregular solids was not a detour, but a productive moment in the development of mathematical abstraction itself. Polyhedra function here as thinking tools, bridging art, craft, and theory. For mathematicians, the book reframes geometry as a cultural practice embedded in making; for designers, it reveals how form-making strategies emerged long before modern design language existed. The Polyhedrists is less about clean solutions than about fertile uncertainty—and that is precisely where its strength lies.

The Laws of Simplicity — John Maeda

The Laws of Simplicity is a small book with a big claim: simplicity is not an accident, but a deliberate choice. Maeda approaches this not by building an academic theory, but with a designer’s instinct—he reduces, groups, and relies heavily on lists. The first few laws are especially strong, reminding us that truly simplifying something often means removing parts of it. The core idea running through the book is clear: simplicity does not live inside the system itself, but in the feeling it leaves with the user. That perspective lands right at the intersection where mathematical thinking meets design intuition.

At the same time, the book is not as smooth as the ideal it describes. At points, too many examples, concepts, and unnecessary acronyms end up obscuring simplicity rather than clarifying it. Still, Maeda’s real contribution is precisely here: he openly acknowledges that not everything can be simplified—and that forcing simplicity can itself create complexity. For that reason, the book works less as a rulebook and more as a mental calibration tool, something to return to from time to time. For mathematicians, it is not a proof but a useful intuition exercise; for designers, a calm yet persistent reminder to think about structure before aesthetics.

Theory of Colours — Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Theory of Colours is a rare and stubborn book that treats color not as a physical datum, but as a perceptual experience. While Goethe openly enters into polemic with Newtonian light theory, his real concern is clear: color is not merely the result of wavelengths, but a phenomenon that emerges together with the eye, the mind, and context. The book ranges widely—from prism experiments to everyday observations, from physiological effects to emotional associations. Readers seeking mathematical certainty may find it demanding, but for those interested in how color is felt, it offers a uniquely fertile ground for thinking.

This is not an easy text to read; it is as obsessive as it is systematic. Yet that is precisely why it remains alive for designers today. Goethe favors observation over measurement, comparison over classification. For mathematicians, the book stands as a counter-thesis; for designers and artists, it reads like an early lesson in phenomenology built around perception, contrast, and effect. Theory of Colours matters less for its claim to correctness than for its power to transform the way we look.

Logo Modernism — Jens Müller

Logo Modernism approaches the logo not as an aesthetic outcome, but as a historical and mathematical mode of thinking. By bringing together nearly six thousand logos from 1940 to 1980, Müller reveals how modernism shaped graphic language: simplified forms, strong geometries, repeated modules, and the pursuit of maximum meaning through minimal gestures. As the pages unfold, the logo stops being an isolated design object and becomes a projection of the technological, cultural, and industrial mindset of its time.

This is not a book meant to be read from cover to cover, but one to think through visually. Even its physical weight signals seriousness. Logo Modernism constantly reminds the reader that design is not intuitive guesswork, but a systematic practice. For mathematicians, the fascination lies in how abstract forms evolve into a universal visual language; for designers, it demonstrates how geometry, proportion, and repetition can construct a logic that remains timeless. It may look like an inspiration book, but its real strength is making the underlying structure of design visible.

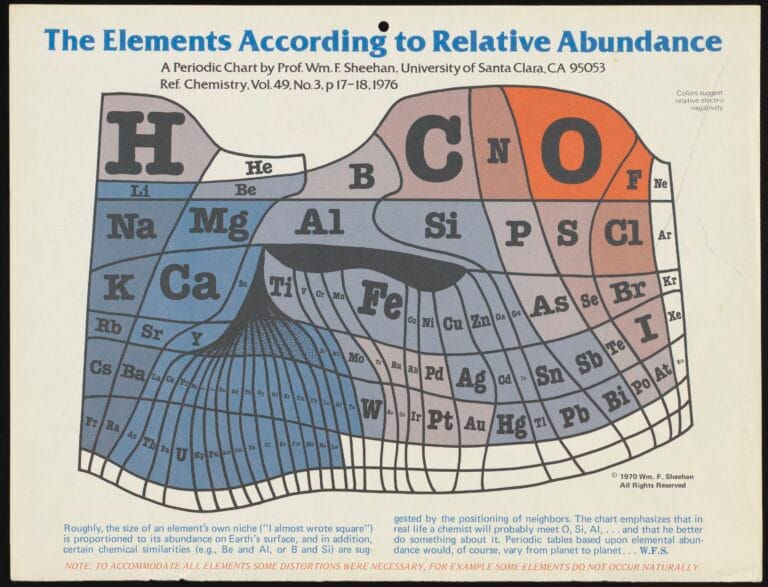

The Beauty of Numbers in Nature — Ian Stewart

The Beauty of Numbers in Nature treats mathematics not as an explanation imposed on nature afterward, but as the language of an order that was already there. Stewart calmly unfolds the mathematical thinking behind forms and patterns—from zebra stripes to snowflakes, from spider webs to sand dunes. This is not a book to rush through; each chapter focuses on a different patterning system and asks the reader to slow down, look carefully, and often return to an idea with fresh eyes. Mathematics here is not an abstract tool, but a practical way of making sense of the world.

At the same time, this is not a light popular-science read. It becomes technical in places, concepts accumulate, and the book demands attention. Precisely for that reason, it works less like a narrative and more like a reference volume—something to keep on the table and open from time to time. Stewart’s real achievement is that he explains beauty without romanticizing it, showing how it can be analyzed, described, and understood. For mathematicians, the book offers familiar ideas seen in new contexts; for designers, it provides a strong foundation for understanding why structures found in nature work so well.

The Golden Ratio: The Divine Beauty of Mathematics — Gary B. Meisner

The Golden Ratio: The Divine Beauty of Mathematics treats the golden ratio less as a mystical legend and more as a proportion that has repeatedly appeared throughout history. Meisner builds the book around a strongly visual language: geometric constructions, ratio overlays, artworks, architectural structures, and examples from nature follow one another page by page. Here, the golden ratio becomes something you grasp by looking rather than by calculating. The book strikes a careful balance for readers who are not far from mathematics but have no desire to drown in formulas.

At the same time, the book carries a persuasive impulse. In some cases, the question of whether the golden ratio was a deliberate choice or a retrospective interpretation remains unresolved. Meisner does not entirely ignore this tension; he acknowledges the existence of controversial examples, yet ultimately leans on the power of visual evidence. As a result, the book reads less like a text that delivers final answers and more like an exploration album that encourages comparison and observation. For mathematicians, it calls for a critical distance; for designers, it offers a rich visual archive for thinking about proportion, scale, and composition.

Snowflakes in Photographs — Wilson A. Bentley

Snowflakes in Photographs is far more than a photo album; it is a record of patience, repetition, and order at a microscopic scale. Over nearly thirty years, Bentley captured individual snowflakes one by one, making visible one of nature’s strictest rules: every flake is built on a hexagonal structure, yet no two are exactly the same. As the pages turn, snowflakes stop being objects and begin to read like geometric characters; symmetry, variation, and boundary conditions can be followed with the eye. Mathematics here is not explained—it is shown.

What gives this book its strength is not technical commentary but visual density. The black-and-white photographs, without excessive explanation, leave exposed the thin line between order and chance. Although Bentley’s work predates modern measurement tools, it remains convincing, because the issue is not resolution but the way of seeing. For mathematicians, the book functions as an archive of patterns; for designers, it offers a quiet yet powerful lesson in how repetition and difference can coexist.

The Geometry of Type: The Anatomy of 100 Essential Typefaces — Stephen Coles

The Geometry of Type treats typography as a problem of structure rather than style. Coles approaches letterforms as systems governed by proportion, contrast, rhythm, and constraint, slowing the reader down and forcing attention onto the mechanics that make type work. Each typeface is presented through large-scale visual analysis, isolating curves, joints, apertures, and stress so that geometry becomes the primary explanatory tool. Letters are not expressive gestures here; they are carefully engineered forms.

What the book does especially well is train visual judgment. Instead of overwhelming the reader with history or theory, it sharpens perception, teaching how to recognize why two typefaces that look similar behave very differently on the page. The Geometry of Type is not about memorizing names or trends, but about understanding underlying relationships. For mathematicians, it offers a familiar world of form, rule, and variation translated into typography; for designers, it provides a rigorous framework for decisions often made instinctively. The result is a book that reads less like a reference manual and more like a disciplined way of learning how to see.

Drawing Geometry: A Primer of Basic Forms for Artists, Designers and Architects — Jon Allen

Drawing Geometry is a calm yet disciplined reminder that geometry begins in the hand, not on the screen. Allen is not after theory here; instead, he shows—step by step—how to draw basic forms such as circles, polygons, arcs, and proportions correctly. Working with a ruler-and-compass mindset, the book makes it clear that geometry is not just abstract knowledge but a physical skill. As the pages progress, the line stops being a mere trace and becomes the thought itself.

The strength of the book lies in its simplicity. There are no long explanations or decorative commentary—only structure. For that reason, Drawing Geometry does not function as something to be quickly consumed, but as a working book to keep on the desk and return to repeatedly. For mathematicians, it offers a return to the roots of form; for designers and architects, it serves as a reminder of how proportion, balance, and accuracy are constructed by hand. This slowness, rooted in pre-digital practice, is precisely where the book finds its value.