From the more mature sabermetric movements of baseball and basketball to growing ones in soccer and hockey, evidence-based examination has led to new thoughts and ideas about the games we love.

But there can also be a dark side to analytics. Among other potential pitfalls, interpreting the numbers incorrectly can lead to terrible decisions or encourage habits that are hard to break, particularly given the added weight that conclusions carry if they appear to emerge from hard data. For an example, look no further than the state of English soccer after it began using what appeared to be a scientific strategy.

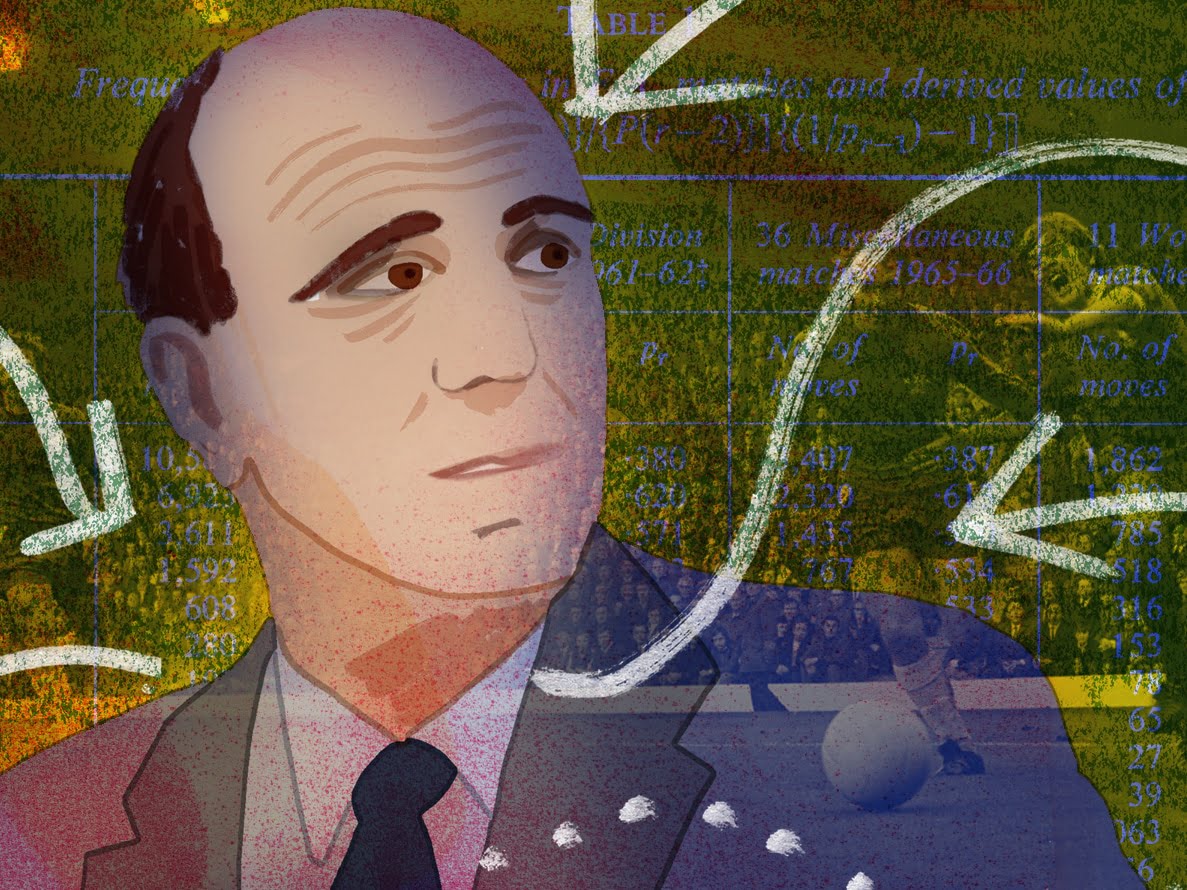

In the latest installment in our documentary podcast series Ahead Of Their Time, we look at Charles Reep, the father of soccer analytics — and a guy who made one big, glaring mistake that changed the course of English soccer for the worse. But in order to arrive at his very wrong conclusion, he first had to radically transform the way people thought about consuming a soccer match.

There was no Opta back in 1950, no Total Shots Ratio, no Expected Goals. But there was Reep, who took it upon himself to attend every Swindon Town F.C. match that season — sometimes with a miner’s helmet on his head to better illuminate his notes — and meticulously scribble down play-by-play diagrams of how everything went down. More than 60 years before player-tracking cameras became all the rage in pro sports, Reep was mapping out primitive spatial data the old-fashioned way, by hand.

Poring over all the scraps of data he’d collected, Reep eventually came to a realization: Most goals in soccer come off of plays that were preceded by three passes or fewer. And in Reep’s mind, this basic truth of the game should dictate how teams play. The key to winning more matches seemed to be as simple as cutting down on your passing and possession time, and getting the ball downfield as quickly as possible instead. The long ball was Reep’s secret weapon.

“Not more than three passes,” Reep admonished during a 1993 interview with the BBC. “If a team tries to play football and keeps it down to not more than three passes, it will have a much higher chance of winning matches. Passing for the sake of passing can be disastrous.”

This was it: Maybe the first case in history of an actionable sports strategy derived from next-level data collection, such as it was. And Reep got more than a few important folks to listen to his ideas, too. It took him a few decades of preaching, but Reep’s recommended playing style was adopted to instant success by Wimbledon F.C. in the 1980s, and then reached the highest echelons of English soccer — channeled as it was through the combination of England manager Graham Taylor and Football Association coaching director Charles Hughes, each of whom believed in hoofing the ball up the pitch and chasing it down (and now seemed to have the data to back up their intuition). The long ball was suddenly England’s official footballing policy.

The trouble was, Reep’s theory was based on a fatally flawed premise. As I wrote two years ago, when discussing Reep’s influence on soccer analytics:

Reep’s mistake was to fixate on the percentage of goals generated by passing sequences of various lengths. Instead, he should have flipped things around, focusing on the probability that a given sequence would produce a goal.