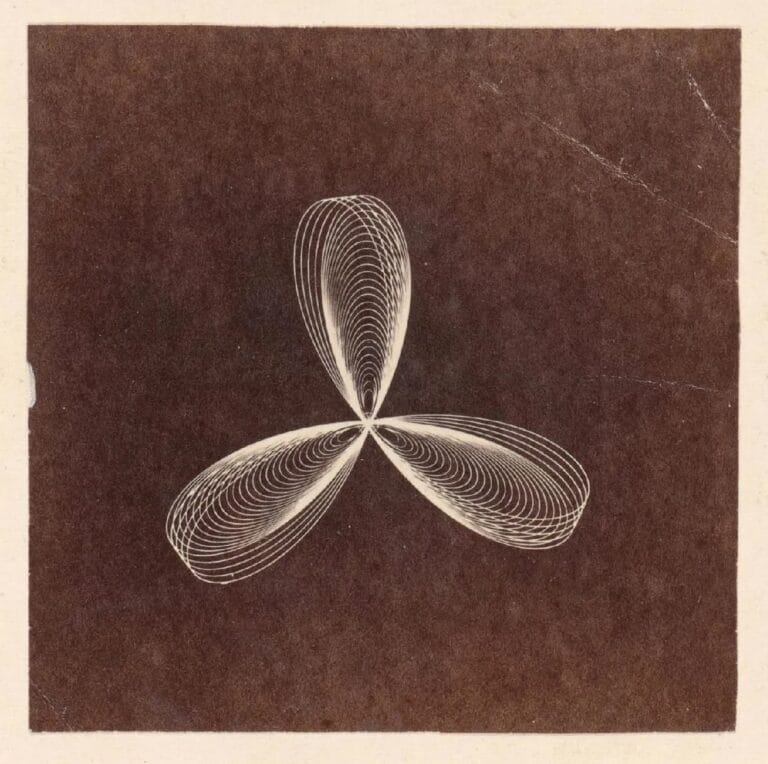

At first glance, these two beautifully worn pages from the 13th-century astronomy manual Al-Mulakhkhas fi al-Hay’a by al-Jaghmini might seem like relics from a long-dead science. But spend a moment with them, and something else emerges: not only the mechanics of eclipses or lunar phases, but an entire philosophy of teaching—one where knowledge is physical, visual, and remarkably durable.

The left page captures a lunar eclipse in a single stroke of geometry: the Sun, Earth, and Moon in alignment, with Earth casting its long, conical shadow. The green rings frame the Earth’s atmospheric layers, and lines radiating from the Sun show how light is blocked or diffused. The diagram doesn’t just depict—it explains.

On the above, a circular diagram elegantly maps the phases of the Moon. Surrounding Earth like pearls in orbit, the eight phases are shown with both position and shading, from the darkened new moon to the full illumination. What today takes textbooks, animation, and apps to grasp, here unfolds in a single analog moment.

Visual Thinking in Medieval Science

This is not just illustration—it’s cognition. Al-Jaghmini lived in a time when astronomy was taught not with abstract formulae or passive readings, but through a rigorous system of observation and diagrammatic thinking. These weren’t just pictures—they were arguments.

Educated in the tradition of Islamic astronomy that extended from Ptolemy’s Almagest, al-Jaghmini wasn’t trying to reinvent cosmology. He was trying to distill it. Al-Mulakhkhas fi al-Hay’a, meaning “The Compendium on Astronomy,” became one of the most widely used textbooks in the Islamic world. Its simplicity was its power.

In madrasas from Samarkand to Cairo, students would sit cross-legged with texts like this, guided by instructors who explained the movements of the heavens through drawn models. Memory followed lines. Understanding followed circles. These were not simplifications in the modern pejorative sense—they were refinements.

The Ptolemaic Universe, Reimagined

Make no mistake: this is a Ptolemaic cosmos. The Earth sits firm and still at the center. The Moon, Sun, planets, and stars revolve around it in concentric spheres. To modern minds, this seems outdated—pre-Copernican, pre-Newtonian, pre-scientific.

But to dismiss it would be a grave mistake. This model, though flawed in structure, was astonishingly accurate in its predictions. Eclipses, planetary motions, seasonal shifts—these were not mystical events. They were calculated, anticipated, and often observed with precision. And most critically, they were made comprehensible through diagrams like these.

What’s more, the diagrams preserved ideas even across language and time. A Persian student could learn from an Arabic manuscript. An Ottoman scribe could copy it centuries later, and a European scholar might recognize its logic without needing translation. Geometry, after all, transcends script.

Pedagogy by Hand

One of the most striking things about these pages is how hand-drawn they are. In an age before print, before mass replication, every book was a unique interface. The colors—ochre red, black, faded green—tell us about the mineral inks used. The slight asymmetries speak of human touch.

Learning astronomy like this wasn’t just cerebral—it was tactile. Diagrams were copied by students again and again, not just to remember but to understand. The motion of the hand echoed the motion of the heavens. In an age without screens, this was kinetic learning at its finest.

Today, educational psychology tells us that visual memory, spatial reasoning, and manual engagement enhance learning. Al-Jaghmini’s diagrams knew this centuries earlier. Looking at Al-Mulakhkhas fi al-Hay’a isn’t just an act of nostalgia—it’s a glimpse into an education system that understood the human mind better than we often give it credit for.

A Legacy Written in Circles

The influence of Al-Mulakhkhas fi al-Hay’a didn’t fade quickly. For over 400 years, it remained a foundational astronomy text throughout the Islamic world. Its diagrams were copied into Persian, Turkish, and Arabic versions. Even when heliocentrism began to seep into Islamic thought, al-Jaghmini’s framework remained pedagogically useful.

Why? Because it wasn’t only about what was true—it was about what was teachable. The best ideas are not just correct; they are also communicable. And sometimes, simplicity is the hardest truth of all.

Compare this to the way we teach science today. Interactive simulations and data-rich apps are powerful, no doubt. But they often obscure the very relationships they mean to clarify. Al-Jaghmini’s lunar diagram is humble—just ink on parchment—but it shows what matters. Where the Moon is. How it changes. Why we see what we see.

Closing the Gap Between Knowing and Seeing

There’s a reason why, even in our digital age, we still reach for the whiteboard. Why professors still draw on napkins. Why children doodle orbits before they can spell them. Because when knowledge takes shape, it sticks.

Al-Jaghmini understood this. In his Al-Mulakhkhas fi al-Hay’a, he didn’t just record astronomical facts. He sculpted them into forms. These two pages—one eclipse, one lunar cycle—are more than medieval science. They are a philosophy of clarity.

Looking at them now, across 800 years, we’re reminded: the most enduring knowledge isn’t just told—it’s drawn. It invites the eye, the hand, and the mind together. And that, perhaps, is where true learning begins.