The classroom grid version of the periodic table is basically a spreadsheet with better PR. Useful, sure—but it quietly trains your brain to believe chemistry is a set of tidy boxes that politely line up. These three vintage posters do the opposite. Each one is an argument. Not about what the elements are, but about how you’re supposed to look at them.

1) The Chemical Elements and Their Periodic Relationships (1975)

The Chemical Elements and Their Periodic Relationships | Source: Science History Institute

This alternative periodic table was made by James Franklin Hyde, known as the “Father of Silicones.” He designed it to showcase how many elements silicon can bond with. Hyde retired in 1973 but stayed on as a research consultant for Dow Corning, and three years into retirement he created this design, published in the student magazine Chemistry in 1975. The table presents the elements in a cooler, less boring way.

2) Table of the Elements in an Irregular Spiral (1940s)

In 1933, chemist—and sci-fi writer—John Clark laid the elements out in a layout that feels less like a chart and more like a racetrack. The idea later got a second life in a more colorful, poster-ready form after LIFE magazine’s 1945 “The Atom” issue helped it spread. This irregular spiral then pushes the same logic further, running the elements (extended up to 104) along a path ordered by electron count while keeping “like with like” visible at a glance. The result is that elements with similar properties naturally cluster into blocks or get tied together with bold arrows, with the inert gases lined up on the left as the easiest example to spot.

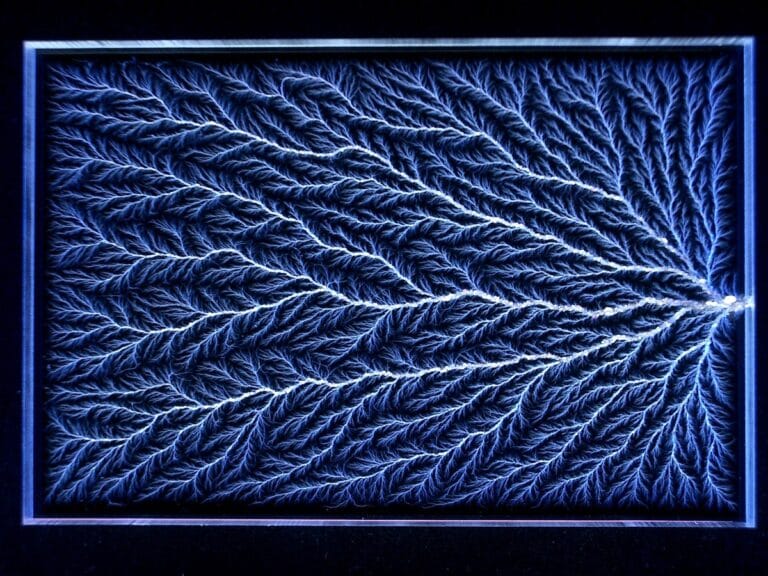

3) The Elements According to Relative Abundance (1970)

This chart isn’t trying to tell you “where elements go,” but rather “how much of them you actually find on Earth.” Made in 1970 by Professor William F. Sheehan at Santa Clara University, it scales each element’s area by its relative abundance on the Earth’s surface, while the colors loosely hint at differences in electronegativity. There’s a reason H, C, N, and O take up so much space here: in real-world chemistry, those are the ones you run into constantly. Sheehan’s note underneath lands on the same idea, pointing out that a chemist will most likely meet O, Si, and Al—and that the real work is figuring out what to do with that trio.